Jerry Lawler says he ain’t gonna wrestle with Hulk Hogan on April 27th at FedExForum. Does that necessarily mean the King ain’t gonna wrestle somebody on April 27th at FedExForum? Well, does it?

In the world of professional wrestling there’s something called “heat.” The expression is used to describe public animosity between wrestlers and the degree to which any given feud is whipping the fans into a frenzy. Heat is desirable. It’s the brutally elegant currency of professional wrestling, and, at 57, Jerry “The King” Lawler still has it.

On April 12th, only a month after his induction into the WWE Hall of Fame, Lawler walked into FedExForum, faced a bank of television cameras, and told a roomful of reporters that, in spite of recent announcements, he wouldn’t go toe-to-toe with 54-year-old Hulk Hogan or participate in Memphis Wrestling’s “Clash of the Legends,” an evening of fictional fighting that local promoter Corey Maclin has described as the largest independently produced wrestling event in the pseudo-sport’s history.

Lawler looked unusually trim as he swaggered up to the mic. His Pepsodent smile and baby blue eyes flashed against his dark Hollywood tan as he excused himself from the bout, citing a conflict between his employers at the Paramount/NBC-owned USA Network and Hogan’s contractual obligations to Viacom’s VH1. Then he left the building.

“I had to get out of there before Hulk came in and VH1 started shooting him for his reality show [Hogan Knows Best],” Lawler explains. But can you trust a wrestler? And more importantly, can you trust Lawler, the man who helped turn wrestling into performance art and blurred the line between entertainment and reality when he teamed up with Taxi star and late comedian Andy Kaufman to perpetrate the greatest entertainment hoax of the last century?

Moments after Lawler’s hasty exit, Hogan stalked up to the stage wearing a tight black T-shirt and his trademark bandanna. In typical wrestler fashion, he bad-mouthed Lawler for breaking his vow that their fight — a grudge match 20-odd years in the making — would go on, no matter what the WWE’s owner and chief ringmaster Vince McMahon had to say about it. Shortly thereafter, former WWE superstar Paul Wight, Lawler’s last-minute replacement, took his turn dissing the WWE.

And so the classic David and Goliath storyline was redrawn: Wight and Hogan would throw down under the banner of Memphis Wrestling as an act of defiance against the all-powerful networks, the WWE, and McMahon’s lapdog, the cowardly and duplicitous King Lawler.

“I wish it really was all just part of some big storyline,” Lawler says, fidgeting with his ever-present Superman ring and swearing that he won’t even be in Memphis on the night of the big fight.

“It’s all about the networks,” he says with a shrug, disappointed that the biggest hometown match of his career has been yanked out from under him. “This is reality and kind of a personal thing [between Hogan and the WWE],” he says. “And it’s a shame, because that kind of reality is what makes for the best storylines in wrestling. When you have something reality-based that has a personal side to it, you can get the fans’ interest much better than you can with ‘Hey, here’s two guys wrestling for a championship belt.'”

Still, sitting on a barstool in his comfortable East Memphis home, surrounded by his Coca-Cola memorabilia, his jukeboxes, and his Disney collectibles, Lawler radiates contentment. And why shouldn’t he? He’s the host of Raw, the longest-running weekly entertainment series in the history of television. “I suppose I could get all mad and quit,” he cracks, only half sarcastically. “But I’m on the top-rated show on USA. And I can have that job for the rest of my life if I want it.” At this point in his career, Lawler has nothing left to prove to anybody. Except maybe Hulk Hogan.

“I was really looking forward to [fighting Lawler],” says Hogan. “I was hoping we could work it out where, at some point, he’d throw a pot of coffee in my face” — a reference to the famous moment in 1982 on Late Night with David Letterman when Lawler appeared to smack the hell out of Andy “I’m from Hollywood” Kaufman, who was still wearing a neck brace from the pair’s clash at the Mid-South Coliseum. Kaufman responded to the attack by tossing a cup of coffee on Lawler and uttering a litany of bleeped profanities that left the famously unflappable Letterman … well, flapped.

That exchange, named by the Museum of Radio and Television as one of the top 100 moments in the history of television, marks the moment that professional wrestling made its jump from niche sport to lucrative mainstream entertainment. McMahon’s over-the-top empire was, to a large extent, erected on Lawler’s and Kaufman’s shtick.

As the WWE became an international phenomenon on cable television, smaller regional wrestling organizations fell by the wayside. Memphis Wrestling, buoyed by some diehard fans, is about all that’s left of the old school. Since Lawler first joined WWE in 1993, the organization has allowed Lawler to work with Memphis Wrestling and put on a show for the home crowd now and then. But when Hogan came into the picture everything changed.

“Sometimes in the wrestling business you cut off your nose to spite your face,” Lawler says. “Pairing me with Hulk Hogan would have generated a lot of interest locally, but now there’s much more national appeal with Hulk going against Paul Wight. After all, that’s the match [the WWE] wanted but couldn’t get for WrestleMania 23.”

Maclin, the Memphis wrestling promoter behind “Clash of the Legends,” agrees that McMahon may have made a mistake, but he also says he was surprised and let down when Lawler, who has worked so hard to keep independent wrestling alive in Memphis, caved to corporate pressure. Maclin, who had already made a $10,000 deposit on FedExForum and placed orders for T-shirts and other merchandise when he got the news that Lawler was out, promises that if this event is as successful as he thinks it will be, there will be more.

“When you can’t deliver the fans what you’ve promised them, you’ve got to bring something better,” Maclin says. “That’s what I think we’ve done. I understand that Vince McMahon has a job to do in New York, but we’ve got a job to do in Memphis too.”

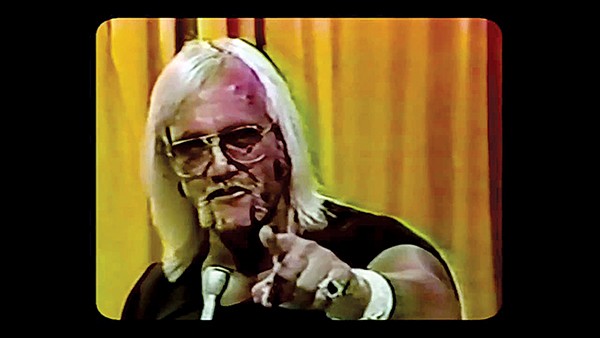

“In a way, McMahon shot himself in the foot at the very beginning,” says Lance Russell, the iconic Mid-South wrestling announcer who began his career in the early 1950s. “All of his original talent came from these regional territories, and when the regional organizations went away, he lost this wonderful training ground. He lost his farm team — where the Hulk Hogans, the Randy Savages, and the Jerry Lawlers learned how to do what they do.”

Russell, who, at 80, is a walking encyclopedia of wrestling history, traces the origins of the modern entertainment back to Gorgeous George, a blond, boa-wearing grappler from Texas who made everyone else in the business seem boring by comparison. And he cites Memphis as the place where all the gaudy pieces came together: the wild characters; the treacherous alliances; the high-stakes storylines; cage and scaffold matches; and a business model built around television. In the 1970s and ’80s, Championship Wrestling was the top-rated Saturday-morning show in Memphis.

“Memphis was like the Wild West,” Hogan says. “Nowhere else have I dodged more razor blades thrown at my head.”

When Hogan was learning his moves in Memphis, Lawler was already the King. In 1975 — six years before Kaufman first visited Memphis, Hogan appeared in Rocky III, and McMahon purchased the Capital Wrestling Corporation (forerunner of the WWE) from his father — City of Memphis magazine reported that Lawler was the driving force behind unprecedented sellout crowds at the Mid-South Coliseum and personally raking in over $90,000 a year.

“He’s the smartest guy in the business,” says Jackie Fargo, Lawler’s trainer, friend, and mentor. “There’s a reason why he’s living in that big old house.” Fargo’s assessment is echoed by Russell, who points to Lawler’s involvement with Kaufman as proof of his business savvy.

“Andy tried to go other places first, but nobody wanted some comedian from a sitcom coming in to make fun of them,” Russell says. “But Jerry saw the potential. And Andy was perfect because he was so genuinely fascinated by wrestling and wanted to learn everything. Andy was particularly amazed at how a wrestler like Lawler could just raise his hand and whip the crowd into a frenzy or into rage.”

“At first, I had no plan to fight Andy,” Lawler still contends. “I was just trying to catch a little heat of the big star who was coming to town.” Before the release of the Kaufman biopic Man on the Moon in 1999, 17 years after the comic first came to Memphis to wrestle women, Lawler finally ‘fessed up, admitting that everything had been a hoax, saying that the two men were friends all along.

“If Andy was still alive, there would have been no question as to who would have inducted me into the Hall of Fame,” Lawler says. “Andy would have done it.” (In Kaufman’s absence, William Shatner performed the honors.)

Helen Stahl, Lawler’s high school art teacher, describes him as one of the five most gifted students she ever taught. “I would look at his drawings and tell him he should be working for MAD magazine,” Stahl says.

Lawler never went to work for MAD, but his photograph did appear in the humor magazine’s most recent issue. And one of Lawler’s lifelong fantasies was fulfilled only a few months ago, when DC Comics invited him to draw Superman for an upcoming comic book project. Lawler claims that art (and Helen Stahl) saved his life, when a commercial-art scholarship to the University of Memphis got him out of Vietnam.

His first big break as an artist was also his first break into the world of the ring. Russell started showing Lawler’s caricatures of local wrestlers on television, and that exposure led to a job painting signs for Fargo, who, along with country-music singer Eddie Bond, co-owned a nightclub and the adjoining Bond-Fargo Sign Painting Company on Madison Avenue. During the time he spent slinging paint for Fargo, Lawler also held down the 7 to midnight shift spinning country records for KWAM radio.

“I remember going into Eddie’s office when he was on the phone,” Lawler says. “He motioned for me to sit down and pick up the other receiver. And it was Jackie on the other end. He didn’t like that I was talking about these outlaw shows on the radio, just like the WWE doesn’t want me doing this outlaw show in Memphis. And he was saying, ‘The kid doesn’t need to be over there wrestling with those punks. Maybe we needed to get a bunch of the real wrestlers together and drive down to West Memphis on Saturday night and break some arms.'”

It was all a bluff, and Lawler called it. No arms were broken, and a week later Fargo invited him to fight on TV in Memphis. All Lawler had to do was talk about Memphis wrestling instead of West Memphis wrestling on the radio. And right up until the time he was fired for playing Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay” on a country station, that’s exactly what he did.

In his early days, Lawler served as a whipping boy for regional stars like Fargo, Tojo Yamamoto, and Nick Gulas. He paid his dues by allowing himself to be beaten up repeatedly for $15 a week.

“I honestly thought wrestling was something I only wanted to try one time, like jumping out of an airplane or riding a bull,” Lawler says. “Now I’ve never tasted a sip of alcohol or done any drugs, but that’s what I compare that first time to: It was like somebody shot me with some kind of drug, and I was hooked right away.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Superman: Jerry ‘The King’ Lawler

Nearly 40 years and 111 title fights later, Lawler is still excited about wrestling. “I never get tired of it, but I do get tired of the travel,” he admits, flipping through his datebook. “This weekend I’m off to San Juan, Puerto Rico, then on to Milan, Italy, then back to San Juan, then to London. It sounds exotic, but it’s all one big security check or waiting in line at the rent-a-car place. It gets old fast.”

Jim Ross, Lawler’s Raw co-host, agrees that being on the road every week is the kind of life that only someone truly devoted to their career would ever want to live.

“It takes passion,” Ross says, “and Jerry’s full of it. And he knows more about wrestling than just about anybody.”

“There are a lot of reasons Lawler has had such a long, successful career,” Maclin says. “He’s helped a lot of people get their breaks. And because of Lawler some of those people are now millionaires.”

Hogan makes no bones about why he agreed to stage his comeback show in Memphis: He thought he was going to use and abuse Lawler the way Lawler used and abused him at the Mid-South Coliseum back when he was still an unknown learning his way around the ring.

“I don’t know why Lawler would break his word to me,” Hogan rails, maintaining the heat.

And just as steadfastly, Lawler maintains he ain’t gonna wrestle the Hulk on April 27th at FedExForum. But with this kind of storyline, how could Memphis’ greatest media prankster not show up, throwing fireballs, pile-driving the bad guys, and yanking the shoulder strap on his singlet down around his waist to show he means business. Memphis, after all, is his city — and he is still its King.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis