The Vice Versa Conventions

by Jackson Baker

CLEVELAND, PHILADELPHIA — At both of the major-party conventions’ conclusions, there was serious tension and distrust between the presumptive nominees’ delegates and backers and those of the runners-up.

At the Republican conclave in Cleveland, this was symbolized somewhat by a scuffle involving the efforts of Mick Wright, a Bartlett delegate committed to Ted Cruz, to make sure that Cruz got the 16 votes he was entitled to when the roll of states was called on the second night of the convention.

Wright had already been involved in a last-ditch effort to deny the nomination of Donald Trump on Monday, opening day, when Cruz delegates and other members of the “Never Trump” contingent tried to force a voice vote on the convention’s rules package.

Normally, this is a routine thing, akin to a city council’s vote to accept the minutes of a prior meeting. But, like that procedure, which often becomes the pretext for reviewing the business at hand before something or other becomes etched in stone, the vote on rules became a test of strength. If successful in getting a vote, the dissidents had in mind some drastic practical changes — their main hope being to strike down the rule binding a state’s delegates to cast their convention ballots in strict accordance with the outcome of their state’s primary.

“Vote Your Conscience,” with its implied permission for delegates to vote as they pleased, was the alternative idea the Never Trumpers hoped to offer as a replacement. It was no secret that in Tennessee, as in numerous other states, the delegate spots pledged to Trump had been filled out with the names of party regulars when not enough activists known to favor him had come to claim them.

Astonishingly, the long-shot “Vote Your Conscience” gambit came near to working. When Congressman Steve Womack of Arkansas, the convention’s temporary chair, called for the Yeas and Nays on accepting the rules, the decibel levels for either side were virtually even. Nevertheless, Womack called it for the Yeas.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

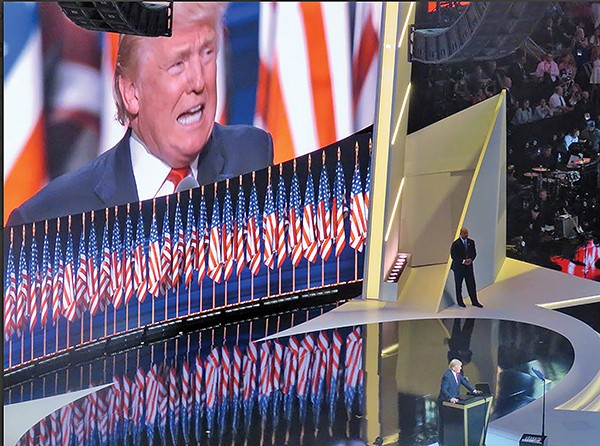

Standing before an array of flags, presidential candidate Donald Trump addresses the RNC.

Thence began a war of voices, with the Never Trumpers chorusing “Roll Call! Roll Call!”, and the Trump forces responding with chants of “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!” As verbal turmoil continued, petitions were circulated in several delegations demanding a roll call as such. And, with various officials shuffling on and off the dais and House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan, soon to be the convention’s permanent chairman, hovering nearby, functionaries representing Trump and the Republican leadership fanned out on the floor, twisting enough arms to get the number of petitioning state delegations below the ceiling needed to force a roll call vote.

After 30 minutes or so of voice votes and re-votes and confusing guerilla theater on the floor, the original verdict against a roll call was held to be valid, and with Ryan taking over as chair, the status quo would never again be threatened.

The civil strife would resume on a piecemeal basis, however, and, in Tuesday night’s roll call to nominate Trump, two states — Utah and Texas — resisted a move toward acclamation and cast their votes for Cruz, who had swept the primaries in both states.

Wright’s rebellion took place the same night. Abetted by Memphian and fellow Cruz delegate Lynn Moss, he took the seat nearest the delegation’s floor microphone, resisting demands from Trump delegate Terry Roland of Millington and others that he vacate it for Mae Beavers, the Mt. Juliet state senator who was delegation chair. Wright documented his side of the quarrel with a smart-phone video of his confrontation with Roland, which became a Facebook post (later deleted).

Eventually Wright was persuaded to move, but he and Moss made sure to be at Beavers’ elbow when the Tennessee vote was cast: 33 for Trump, 16 for Cruz, and 9 for Marco Rubio.

In a sense, all this solicitude for the runner-up was for naught. Whatever loyalty Cruz might have extracted from his Republican base was squandered the third and penultimate night of the convention, when the Texas Senator, given a prime-time spot as runner-up, made what sounded like his opening salvo for the presidential race of 2020, omitting any reference to Trump beyond a thin and bitter-sounding “congratulations” and invoking the insurgent phrase, “Vote your conscience,” as his recommendation vis-à-vis the November ballot.

As it turned out, it was the best favor Cruz could have done for Trump; his behavior was almost universally regarded as churlish, and the consensus was that he had not only scotched his presidential hopes for four years hence but also removed himself as a rallying point against Trump’s takeover of the GOP.

Against all the odds he had faced since his declaration for the presidency in June of 2015, Trump had his unity at last. Granted, the obligatory lineup of speakers praising the nominee had run a bit short. The convention had been boycotted by a Who’s Who of Republican heavyweights: McCain, Romney, anybody named Bush were among the missing. Even John Kasich, erstwhile presidential contender and the Governor of Ohio, the host state for the convention, had absented himself.

Ironically, Trump’s best foot forward may have come from a turn by Melania, his Slovenian-born wife, a former model who gave a well-received speech saluting the American dream and emphasizing such verities as honor, hard work, and personal responsibility.

That the speech had been ghost-written — like almost all the speeches by everyone at either convention — was not an issue, though the fact that some of the phrases were those, word for word, of the ghost who had written a convention speech eight years earlier for Michelle Obama, deservedly became one.

There had been a Chris Christie here, a Rudy Giuliani there, and a smattering of Grade-B actors, token blacks and Hispanics, as well as a whole night of grieving and/or outraged Benghazi survivors — all this against a nonstop crescendo of Hillary-bashing and holding her to account, it seemed, for all the deaths and misfortunes not only in Libya, but at the Mexican border, and on the streets of stressed-out America. And, of course, there was the potential high treason of her emails.

Therein lay the main glue that could bind the rest of the GOP to the Trump machine, such as it was, including, besides the Boss himself and Melania, an impressive array of well-scrubbed and well-spoken offspring, all of whom got their own star turns at the dais.

All the while this truncated Trump/GOP convention had been going on, delegates and guests had been entertained at spells by a string of Golden Oldies rendered by the G.E. Smith Band, late of Saturday Night Live. As balloons dropped and confetti flew and delegates on the floor sported in the aftermath of Trump’s 76-minute acceptance speech, the recorded strains of another rock classic filled the arena, the Rolling Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.”

Nor were the auguries promising for the Democrats as they flooded into Philadelphia for their party’s convention. For one thing, the heat index in the City of Brotherly Love would stay in the triple digits, exacerbating such tensions as were already there. And tensions, indeed, there were.

In the weekend between the two conclaves, there had been a Wikileaks drop of emails between officials of the Democratic National Committee, incriminating ones suggesting a concerted effort by DNC mainstays to back Hillary Clinton and to block her populist challenger, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

Before the convention even got started, DNC chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz was forced to resign, turning over her gavel to a substitute, and Sanders delegates, who constituted just under half of the total number present, understandably were subject to a feeling of estrangement; given the evidence, it was hard to call it, as some did, “paranoia.”

One of the after-effects of the WikiLeaks disclosure was to further swell the number of protesters who were confined within a mile or two of fenced-in parkland directly adjacent to the Wells Fargo Center. The number of people jammed into that space — mainly youthful but including some old soldiers of the left, as well — went well into the thousands, all hindered by the insufferable heat and a lack of provisions, save for whatever food and drink they might have packed for themselves (or, alternatively, was provided by park-service units or by a good Samaritan group or two).

Do not imagine some Woodstock of the carefree and discontented. This was more on the order of a penal camp — a political ghetto, even — for all the revved-up spirits here and there, the intensity of the calumnies (mainly directed at Hillary or the DNC) in the signage, and the resort to “Power to the People” and other vintage slogans. Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein had a tent, and there were tents for other pretenders and dissidents, and periodic efforts to make music on an outdoor stage.

Inside, the array of opening-day speakers was clearly designed to generate a sense of conciliation. First Lady Michelle Obama won hearts and plaudits with her eloquent recounting of generational progress and the sense that daughters Sasha and Malia might in their turn aspire to the presidency. Senator Al Franken and Sarah Silverman did a goofy send-up of the Clinton-Sanders rivalry designed to heal it over. Senator Elizabeth Warren was there to formally join her corner of the party’s reform wing to the cause of Hillary Clinton, and there was finally the pièce de résistance — Bernie.

Sanders did all that the Hillary camp would want. He declined to exploit the WikiLeaks revelations and did his best to smooth things over. “Any objective observer will conclude that — based on her ideas and her leadership — Hillary Clinton must become the next president of the United States,” he said. He parroted one of the ad lines designed for Clinton supporters: “I’m with her.” And, ignoring Trump’s affected solicitude for him, Bernie blasted away at the GOP candidate, linking him to reactionary positions on climate change, taxes, health care, and a minimum wage.

Even so, not all of Sanders’ supporters, either in or outside the arena, were reconciled with Clinton, as events would demonstrate. And this was a two-way proposition. Throughout the evening, delegates and audience members had remained in their seats, enduring any number of scripted warm-up speakers and the over-praised bombast of New Jersey Senator Cory Booker.

As Sanders prepared to speak, there was an observable trickle of people off the floor and out the exits. Given the high degree of anticipation for what Bernie would say, this almost had to be a counter-protest of the Hillary contingent.

Nor were the Clinton and Sanders camps ever totally conjoined. Throughout the convention there were bitter words back and forth, in the Tennessee delegation as elsewhere. During the ritual roll call on Tuesday, TV cameras showed the numerous seats left vacant by Sanders delegates, several of whom took to the hallways of the arena, posing with duct tape over their mouths, apparently to indicate, like the Cruz delegates in Cleveland, that they were victims of suppression.

Clinton delegates from the Memphis area, like David Cocke, Adrienne Pakis-Gillon, and David and Diane Cambron, would periodically express exasperation at various tactics of Sanders delegates, who tended, they said, to claim blocs of seats and even whole rows for themselves, barring Clinton delegates from them.

Even on the convention’s final day, during the coronation speech of Hillary herself, the more diehard of the Sanders delegates sat together in clusters made highly visible by phosphorescent-appearing green-and-yellow T-shirts.

The afternoon and early evening of that last day had been largely devoted to displays, atypical at Democratic conventions, of strident patriotism, featuring a veritable forest of flags that had been passed out, and as a highlight of sorts, a war-like address from Marine General John Allen, a former commander in Afghanistan, who thundered against ISIS and other foreign enemies and against Republican nominee Trump with almost equal fervor.

To all of this pockets of the Sanders people on the floor would chant “No More War!” and would be answered with countervailing choruses of “U.S.A.!” reminiscent of the rules-challenge cacophonies of the GOP convention.

A military sense even tinged the most telling moment of the Democrats’ final day, and perhaps of the entire convention, the reproaching of Trump for his anti-Muslim sentiments by immigrant couple, Khizr and Ghazala Khan, whose son, Army Captain Herayun Khan, was killed in Afghanistan.

In a way, both presidential candidates, Republican Trump and Democrat Clinton, would close their conventions by presenting themselves against type — Trump by appealing to the followers of Bernie Sanders to switch their allegiance to him as an agent of populist change; Clinton by her efforts to appropriate the symbols of the status quo and of militancy. For better or for worse, both succeeded to some degree.

Clearly, Trump is basing his campaign, as he did during the Republican primaries, on convincing a dormant bloc of voters out there that he is the only hope for a radical change in American government. Though he has made an effort to match up traditional Republican talking points, he is more sui generis than a conservative per se.

Just as clearly, Clinton wants to peel off suburbanites and traditionalists who normally vote Republican, while maintaining some degree of control over the unruly forces of reform represented by Sanders. Husband Bill Clinton’s extolling of her as a “change maker” on Tuesday night was a move to that latter end. But she is not a true person of the left.

The residual tensions in both parties, so plainly seen in the events of the two conventions, reflect what is an uneasy transition in the constituencies that each party represents. And, for that reason, this presidential election is going to be a difficult one to call.

[slideshow-1]

Before the Flood

by Chris Davis

Somewhere in the distance somebody was playing “God Bless America” over a loudspeaker. The female singer’s voice wafted over the squall of sirens, cutting through the roar of dissent and the “step right up” patter of souvenir merchants selling T-shirts and buttons with slogans like “WTF GOP” and “Hillary for Prison.”

The scene outside Philadelphia’s Wells Fargo Center, where former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton accepted her party’s nomination to become America’s first real presidential contender with a pair of X chromosomes was chaotic and characteristically weird. It looked like one of those scenes you can find in practically every Walking Dead episode, where a narrow stretch of chain link is the only thing separating scrappy human survivors from the swelling undead horde.

In this case, protesters — mostly young Bernie Sanders supporters — pressed their bodies against the temporary fencing at the outer edge of the Democratic National Convention’s security perimeter, pounding steadily at the expanded metal with knotted fists and fleshy palms. Some demonstrators chanted anti-Democrat slogans; others — including some you’ve probably seen on TV explaining their positions to the nation — wore gags to signify how they’d been silenced by a rigged system. Bernie’s hopeful, hard-fought campaign may have expired, but its decaying husk pressed forward.

I was moving away from all that noisy democracy, when I saw more flashing blue lights headed into the thick of it. Someone had jumped the fence to get arrested and obtain civil disobedience “likes” on Instagram. There was no clear purpose in going over the fence so far from the arena and the news crews. Like all those steaming horse turds littering Cleveland’s streets during the RNC, this had to be a metaphor for something.

Sanders, who staged a formidable campaign built around issues such as income inequality, jobs, and getting big money out of politics, is now a (mostly) full-throated advocate for his recent opponent, Hillary Clinton. But the gruff message he brought to DNC delegates as he made the breakfast meeting circuit, sounded like one of his stump speeches. Sanders may have lost the nomination, but the old, woolly haired socialist’s consolation prize is the most progressive Democratic platform in history.

When he visited the Tennessee delegation last Thursday, arriving late and looking tired, the gruff lion of the newly woke left stated in explicit terms that job No. 1 was defeating Trump in November. Job No. 2, he said, was holding Clinton accountable for the aforementioned platform.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Protesters hold aloft a larger-than-life Sanders cutout outside the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia.

“We do politics a little differently,” he said, and he continued to speak about disruptive political change and the need to elect young progressives to school boards, city councils, and state legislatures, to grow revolution from the ground up. In the streets, Sanders’ most disappointed and disillusioned supporters said, “Hell no, DNC, we won’t vote for Hillary” and waved signs transforming the Senator’s own unifying rhetoric into a kind of separatist mantra.

“It isn’t him,” the signs read, “It’s us.”

When things get chaotic, as they often do at these kinds of enormous public demonstrations, it’s helpful to focus on your destination. Keep moving forward and don’t look back is a lesson I learned the hard way in St. Paul during the 2008 Republican National Convention. Protesters sick of Bush-era lies, endless war, and circumstances that call to mind Tennessee Williams’ line about “the fiery braille alphabet of a dissolving economy” had been clashing with law enforcement in front of the Minnesota Capitol all week. I almost met an abrupt end running to evade a column of riot police who’d marched into the free speech zone and were dropping and zip-tying everybody in their path — protesters, media, gawkers, whomever. When I turned back to film the mass arrests, I was nearly trampled by a second column of horse-mounted police thundering in from behind.

Tensions in Cleveland and Philly never reached that kind of fever pitch, and so, on that sweltering afternoon 48 hours before Clinton’s big speech, I followed the music, which turned out to be the work of just one man parked in a CVS parking lot across the avenue playing patriotic songs on an extraordinary car stereo. On the sidewalk in front of him a clean-cut young guy with a Sanders sign dropped a dubious truth bomb on his wholesome-looking girlfriend: “Sure, that man told you he was just taking a picture,” he scolded, looking around to make sure nobody was watching. “But how do you know he wasn’t with the Secret Service? How do you know that was really a phone he pointed at you? In one click that guy probably just got all of our information.”

Could be that he snatched away the poor girl’s soul too, bro?

Sampling that conversation isn’t fair to diehard Sanders supporters, but it speaks directly to the America I glimpsed on my long drive from Memphis to Cleveland to Philadelphia to Memphis again. From the mountains, to the prairies, to the Starbucks where chipper young men carry AK-47s, paranoia reigns. If you don’t believe me, take a trip through Burma-Shave where there’s a billboard every few miles reminding drivers that God’s watching, and when you die you’ll meet him. Or better still, say the name of the Republican nominee out loud, and remind yourself what he stands for.

Open-carry advocates aside, protests at the RNC in Cleveland had a colorful throwback vibe that paired nicely with Trump’s dystopian motivational speakathon, and a bitter-edged acceptance speech that segued into Free’s classic sleaze-rock anthem, “All Right Now.” It was a loud free-for-all, where members of Code Pink donned their trademark color to lead anti-fascist cheers from the sidewalk while Westboro Baptist-types paraded up and down with enormous signs asking, “GOT AIDS YET?”

Clowns performed street theater in the public square, and the only time things seemed to really get out of hand was when a group of young radicals chanting, “America was never great,” attempted, as young radicals will, to burn a flag. This resulted in an altercation with some religious zealots. Or was it bikers? Maybe it was a combination of religious zealots and bikers or religious zealot bikers. Word on the ground kept shifting, and all anybody really knew was that horse-mounted police came from one side, bicycle-mounted police rolled in from the other, and things got pretty orderly pretty fast.

There was a strong police presence in Philly, but Cleveland looked like occupied territory. Closed streets just outside Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena took on the life of a casbah, where people sold bad ideas and Donald Trump bobbleheads side by side. Sexism was a hot commodity, too, and T-shirts reading “Hillary Sucks but not like Monica” and “TRUMP THAT BITCH” flew off stands at $20 a pop. So did buttons marketing the Hillary Meal Deal: “2 small breasts, two fat thighs, and a left wing.”

In the wake of a march led by conservative Christians, several young men stood in the streets near a massive pile of horse shit, pushing their phones into the face of a teenage girl. They asked her to explain for the camera why she didn’t think she was a whore.

“I’m just a 16-year-old girl,” she answered, as more and more people stopped and took out their phones. “I’m probably going to lose my job,” she said, eyes darting from recording device to recording device. “I’m speechless.”

It’s trite but true: America is a beautiful country full of natural wonder and storybook villages. I’ve driven through much of it over the past two weeks. Also — as the would-be flag burners might say — it’s an ugly, exploitative wasteland, bubbling with bigotry and rigged systems. Anybody who tries to convince you it’s one or the other and not both is running a con.

Speaking of cons, have you heard about the Ark Encounter theme park near Williamstown, Kentucky? It’s an enormous $100-million, mobility-scooter-friendly religious attraction inspired by the Biblical account of a universal flood. This great windowless, oarless, rudderless, landlocked boat is the largest wooden structure in the world, built with lumber from 200-year-old trees. All that fresh timber smells like God’s love with just a hint of vengeance, and for the low cost of $40 per adult (plus $10 parking), visitors can tour the Ark’s animatronic exhibits and see robot dinosaurs being hand-fed by teenage robot girls. You can learn about how, in spite of what experts may tell you, planet Earth is only 6,000 years old.

Buying a tub of hummus and a $10 souvenir soda cup from the ark’s attached restaurant may be the single most American thing I’ll ever do.

Trump hat count: three.

What does all of this mean? I wish I could tie it up in a red, white, and blue bow, but the lessons of this journey are a little too fresh and way too stubborn for that. I think it’s got something to do with tribes and personal brands and how everybody’s selling a different story, and how, in spite of what Al Pacino teaches us in Scarface, everybody’s doing their own product.

Dissent and all, I suppose the conventions were good for Democrats, who addressed at least some of the complexities of the America I saw on my trip, framing hopeful narratives with the palpable grief of citizens like Trayvon Martin’s mother, Sybrina Fulton, and the Muslim-American parents of U.S. Army Captain Humayun Khan. The GOP’s two-pronged event spent so much time attacking Clinton and praising Trump, it gave Democrats the opportunity to talk about real values and real people. Now it’s all a question of who’s listening, who’s believing whom, and who’s buying tickets to the Ark Experience.