Painter and former gallery owner David Mah stands in front of 20 first-graders at Idlewild Elementary. He’s wearing a black shirt, khakis, and a full-length apron.

“What do we do first?” he asked the students.

“We clean our brains!” they yell.

Mah takes them through a series of pantomimes. They get out their keys and unlock their brain, take it out of their head, dust it off, clean it, polish it, floss it — waving their hands on either side of their ears — then move to their eyes.

They mime taking each eyeball out and putting it in their mouths — “I swallowed mine,” says one boy — and Mah ends with a flourish, “tossing” his eyeball in the air before popping it back into the socket.

“A 30-year-veteran teacher told me about that technique,” Mah says a few days later. “It’s a great focusing exercise. It gets them to listen to me; it gets the wiggles out; and they love it.”

Mah is one of about 100 elementary school art teachers hired by the Memphis City Schools at the beginning of the 2007-2008 school year. With funding from new state cigarette-tax money, MCS decided to spend more than $5.7 million to put an art teacher into every elementary school.

At the time, there were only 18 elementary art teachers for the district’s 112 elementary schools.

“In the old days, schools would say we can get art or we can get music,” says Gregg Coats, the district’s coordinator for visual arts and theater. “I got called in July 2007 and was assigned to put an art teacher in every [elementary] school that didn’t have an art program.”

Coats began by calling the University of Memphis and the Memphis College of Art, looking for students with a background in art education. After he exhausted that pool, he still needed a daunting 60 more teachers.

That’s when he turned to an untapped market: local professional artists, such as Mah, Lurlynn Franklin, Bobby Spillman, Emily Walls, and David Hall.

It may seem either an unlikely or inspired choice. Some, such as Jami Hooper, had experience teaching elementary children. Others, like Mah and Spillman, had taught college courses but not younger students.

Speed was of the essence. Because of the short time-frame between the funding and the start of the school year, many of the new art teachers were hired one week and in a school the next.

Under the alternative licensure program, people who don’t have a degree in education but are highly qualified in an area can teach it temporarily while enrolled in a teacher education program. These teachers knew the subject matter. Beyond that, it was something of a gamble.

“These 60 people are teaching full-time and going to school to take the coursework needed for licensure,” Coats says. “And they’re trying to hold onto a life, too.”

The first year the district found grant money to help the new teachers — commonly called the “Bredesen teachers” — with tuition reimbursement. But with funds tight at the district, the teachers are paying for their licensure classes this year.

“The first year was a big transition period,” Coats says, though only four of the teachers chose not to return the following year. “They all looked like deer in headlights.”

Getting Started

“In my opinion, we’re probably getting the best on-the-job training you could ask for,” Spillman says. “It’s basically sink or swim.”

Bobby’s wife, Melanie, was working for the UrbanArt Commission when she decided she wanted to teach English as a Second Language in the district. But Coats asked her if she would be interested in teaching art.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Artist Lurlynn Franklin teaches symmetry at Lincoln Elementary.

“I said, what do you mean, Gregg? There aren’t any art positions,” she says.

But with $42 million in additional state funding, there were. The district decided to use the money — known as BEP 2.0 — for intensive support for schools on probation, to improve teaching, and to expand academic and student support programs.

After his wife was hired at Cordova Middle School, Bobby Spillman also interviewed for a job. “At the time, I was teaching painting at the Memphis College of Art; I was doing courtroom drawing; I was doing a little bit of cooking at Bari,” he says. “I had a lot of things going on. I was ready to burn out.”

As far as the curriculum goes — studies in color, shape, and texture — the new teachers were supremely qualified. But it’s a daunting proposition to stand in front of a roomful of excited children and teach them how to draw, much less paint, while maintaining some sort of order.

Bobby Spillman, going from teaching college students to teaching at Bruce Elementary on Bellevue, says the first month was pure “trial and error.” Even simple assigments could have pitfalls.

“There were some things I realized we can’t do again,” Spillman says. “We did ‘Where do you live?’ drawings, and some of them drew gymnasiums. At first I thought they were apartment buildings. Then I realized they were shelters,” he says. “When I first started, the assignments were ‘things that are.’ Now they’re ‘what could be.'”

Part of his challenge was how tightly knit the Bruce community is. Some of the teachers are grandparents of students who attend the school. Parents often drop in. Spillman was the new guy. The school hadn’t had an art teacher in several years.

“The first two months, I badgered the teachers to stop calling art ‘fun time,'” he says. “It does look like fun time and it should, but … this is required. You can’t punish your kid by saying you can’t go to art today.”

Fortunately, their backgrounds in art have prepared them to be flexible and creative.

After his kindergarten students mastered drawing squares, Mah thought he would teach them to draw cubes. He passed out rulers and graph paper. But the children didn’t understand.

“When I asked them what they didn’t understand, they said, ‘What are these wooden sticks with numbers on them?’ I said, ‘The rulers?'” Mah says. “Then I said, ‘Today we’re going to be drawing straight lines.'”

Mah has been an artist for 25 years. He calls last year “stressful.”

“I don’t have children myself. I knew about art, but I didn’t know anything about kids or classroom management,” he says.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

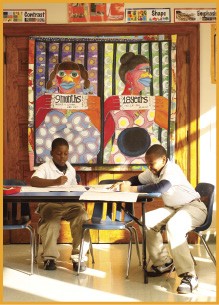

Painter David Mah pantomimes with first-graders at Idlewild Elementary

When he showed up at Idlewild, he was standing in the principal’s office when she received an e-mail that said he was coming. The school hadn’t had an art teacher in more than a decade.

“She had to find me a classroom,” Mah says. “The first day, there was a class of kids looking at me, and I think I even told them, I have no idea what I’m doing. I passed out papers and told them to draw whatever they wanted.”

Group Work

Coats, a former art teacher at Whitehaven High School, jokingly calls the Bredesen art teachers his “kids.” It’s fitting. At the district, he coordinates their professional development.

But Jami Hooper, the art teacher at Peabody Elementary in Cooper-Young, seems more like a mom. A nine-year veteran classroom teacher with a big smile and a calm demeanor, she was “surplused” (a polite term for laid off) from her position as a fifth-grade teacher at Bruce Elementary a few years ago, after enrollment dropped.

“At the time, it seemed like it was the worst thing in the world,” she says. “I went to several schools looking for another position. At the last school on the list, they said all we have is an art position.”

A sculptor and painter, Hooper is a natural. As she mixes paint with white and black to create tints and shades, the students stand around her, looking on in awe. “She’s an artist,” they whisper. And: “It’s so pretty.”

In the former science lab turned art room, she uses all the teacher tricks: raising a finger in the air for quiet, clapping rhythmically to get students’ attention — they clap back in time — having her students finish her sentences, and giving them playing cards when they’re doing a good job.

“The cards are just positive reinforcement,” she says, when asked about them. “Anytime you see them doing something right, you put one down in front of them. It’s a good visual. And if they’re not following directions, you take the card back.

“It’s been a lot easier for me than some of the other art teachers, because I’ve been in the regular classroom.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Though some of their experiences have been frustrating, the Bredesen teachers have had help: each other. The artists — especially those working on their licensure — see a lot of each other: They attend classes together at MCA or the U of M. They have professional development sessions with Coats, and many of them still attend weekly gallery openings on Fridays.

“It’s also kind of therapy,” says Sallie Sabbatini, a diminutive photographer and filmmaker who is “art on a cart” at Raleigh Bartlett Meadows Elementary School. (Because she lacks a regular classroom, she goes room-to-room with a cart of art supplies.) She also teaches at Egypt Elementary.

“There are a lot of us, so there’s a great camaraderie,” she says. “We were all hired at the same time. If I had been hired all by my lonesome, I don’t know what I would have done.”

Show and Tell

When the new art teachers began last year, a few of them noticed something: There was virtually no difference between the art skills of their fifth- and first-graders.

“They all struggled to draw squares and triangles,” Mah says.

Under No Child Left Behind, art is considered academically core. For its proponents, art helps students in many ways. It gives them an outlet for creativity. It can give them self-confidence. It develops problem-solving skills.

“I’m kind of hard on them,” Sabbatini says. “If they make a mistake, they have to figure out how to work around it. I’m not going to give them another piece of paper.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Students work in front of a painting by Lurlynn Franklin.

She also thinks art class gives them something that many of them haven’t been getting at home.

“It’s been depressing to find out how poor this city is,” she says. “A lot of kids don’t have crayons and pencils at home. We have to go back to the basics and fundamentals of art.”

A young woman who barely looks older than her students, Sabbatini has several little boys who cry every time they’re asked to draw a circle.

“I’ve made them templates of circles, but they have to get past that. I’ve called and asked their parents to work on their shapes with them at home. It’s a learning curve for all of us, because parents are already working so hard.”

Other teachers at Sabbatini’s schools have also realized how art can influence student behavior. Sabbatini has had several students with ADD start keeping a sketchbook.

“They might not do well in the regular classroom, but they will be the best artist in the class,” she says. “Their sketchbooks calm them down, and they’re a tool that can even be used in their regular classrooms to keep them busy.”

Hooper says she’s a big believer in art because it gives school students — usually so focused on achievement tests — a way to express themselves.

“A lot of kids are so used to doing fill-in-the-blank work. When you tell them that it doesn’t have to be like his or hers, it’s your artwork, there’s just something that happens,” she says.

But if the students are excited about art, Coats and the Bredesen teachers are excited to see the students’ work after five years of elementary art.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Sallie Sabbatini prepares for her first-graders

Melanie and Bobby Spillman both say they run their classrooms similar to the way they ran their college drawing classes — the younger students just soak it up that much quicker.

“You show them and tell them and they do it,” Melanie says. “They’ll come back the next day with 15 of them.”

What do working artists bring to the classroom? Maybe it’s experience or a voice of authority or the possibility of a future.

“My students say, ‘Mrs. Spillman, how do you do this in your studio?’ I think they really respect it. You wouldn’t want to take your car to a mechanic who doesn’t drive,” Melanie says.

Her husband, who didn’t have an art teacher until he was in high school, is cultivating a drawing program at Bruce. He adds, “My kids Google me. I think it validates the fact that I can teach you to draw.”

Or maybe just having art in every elementary school is enough.

Lurlynn Franklin has seen her students win awards without having much of an art background.

“These kids were hungry for it. When they go to junior high and high school, they are going to be something else,” she says. “This is going to blow up.”

The Student as Teacher

In Franklin’s classroom at Lincoln Elementary, she has one of her pieces on the wall. On one side is a mug shot of a pregnant woman who is sentenced to nine months. The other side is a mug shot of a mother sentenced to 18 years.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Students learn primary colors with painted butterflies

On this particular day, a class of fourth-graders is working on quilt panels. As they work, Franklin walks around the room offering critiques:

“We are going to change your name to Photocopy.

“He needs to be larger. He’s a superhero, and he’s that tiny?

“I know you love America, but you can’t just use red and blue,” she says and stops in front of a girl coloring hearts. Franklin points to a box of markers. “Close your eyes and pick a color. Now another. And another. Work with those three, so you don’t get stuck on stupid.”

Franklin has taught high school students before and done six-week residency programs in elementary schools, but this is the first time she has taught art full-time. She calls the experience “eye-opening.”

“It’s like I’m refamiliarizing myself with line and color,” she says. “I feel like I’m more open now.”

Franklin also finds her own work dealing more often with children. A recent show at the CBU gallery dealt with children and consumerism.

“I’ve been thinking about why are they so materialistic now. The greatest thing on earth was making them wear these [school] uniforms,” she says.

Teaching also means the benefit of a steady paycheck, giving Franklin more freedom to take chances with her own work.

“I’ve got a job. I can paint whatever I want,” she says. “You can’t tell me what to paint. Sometimes finances kind of mess with your creativity.”

Many of the Bredesen teachers say that being in the classroom has influenced their work in one way or another.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Melanie Spillman at work in her studio

Since joining MCS, Mah has stopped painting, simply because there isn’t time between teaching and his education coursework.

“Oftentimes, I’m jealous of the kindergarten and first-graders because they still have an uninhibited way of expressing themselves with their drawings,” Mah says. “It’s just scribbles, but if it were 7 feet by 7 feet, it would be an amazing painting.”

Hooper, on the other hand, now gets into her studio three or four times a week.

“As a regular classroom teacher, I came home drained, and you’ve always got more work to do. Now I have all these creative juices because I think about art all day long. A lot of the things I do with the kids give me ideas about what I can do at home.”

She’s not the only one. Melanie Spillman’s students work mostly with pencil and paper. For her recent “Ties That Bind” exhibit at Marshall Arts, she worked with the same materials.

“It’s given me more energy,” she says. “It fuels my fire.”

Her husband agrees.

“Watching kids at that age, I can remember how it started for me,” Bobby Spillman says. “You can tell which ones are a little bit more advanced and more naturally gifted than the others. I enjoy watching artists of any age, but this is where I need to be.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks