The Redeemers

By Ace Atkins

Putnam, 370 pp., $26.95

Ace Atkins, a former journalist, lives in Oxford, Mississippi, where he cranks out some very good crime fiction. The Redeemers is the fifth novel in Atkins’ “Quinn Colson” series. Colson is 30-something, a hard-bitten former ex-Army Ranger commando, who became sheriff of fictional Tibbehah County in the hill country of North Mississippi.

It’s a country populated by some colorful folks: mean-ass crooks, horny safe-crackers, a shifty topless-club owner, a murderous sniper, a sleazy state trooper, former crack-whores, strippers, drunks, divorcées, and assorted other characters. And there are some bad guys, too.

As The Redeemers begins, we learn Colson is serving his last couple of days on the job as sheriff, having been voted out of office, replaced by a local insurance agent controlled by a local bad guy. But before Colson can get out of town, things blow up big in Tibbehah. Two local yokels with dreams of a payback hire a couple boys from Alabama to come in and help them crack a safe.

Suffice to say, things don’t go as planned. A deputy gets shot, and the ‘Bama boys are on the loose with a safe — a safe that holds a million dollars and documents that can expose crooked dealings in high places in the state of Mississippi.

Atkins weaves a compelling plot and his characters … well, let’s just say if you’re from around here, you’ve met them or people just like them. And Colson is a likable protagonist in the “strong, silent type” mold, with a weakness for a local married woman and plenty of family complications of his own. But mainly, he’s a bad-ass. A real bad-ass. And the payoff in these novels comes in the big, bloody showdowns that make the last 40 pages go so quickly. The action is tense and well-crafted. Colson’s outnumbered, he’s wounded, he’s trapped in an impossible situation, he’s going have to kill or be killed.

Sure, you can’t think too hard about how any man with only one arm and a knife could take out two armed men who have the drop on him. But that’s part of the fun. He’s Quinn Colson, dammit. Just enjoy the action. And it’s good action. — Bruce VanWyngarden

Ace Atkins will be signing The Redeemers at the Booksellers at Laurelwood on Sunday, July 26th, at 4 p.m.

All the Light We Cannot See

By Anthony Doerr

Scribner, 544 pp., $27

Is there beauty to be found in war? Certainly not in the grotesque rationalizations behind why one country invades another or why brothers take up arms against brothers. Certain authors, though, have recently found great success — and great beauty — in writing against the backdrop of the ugliness of war.

Julie Orringer’s 2010 novel, The Invisible Bridge, follows the divergent paths of brothers in 1937 Hungary. And most recently, Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize-winning All the Light We Cannot See pares down the invasion of France by Germany to the basics of life — family, love, loyalty, safety — written with heart in a way that each of us (many of us untouched by war) can relate.

In All the Light We Cannot See, blind Marie-Laure LeBlanc lives with her father, a locksmith. When the Nazi occupation becomes imminent, the two flee to a seaside garrison town and the house of Marie’s great-uncle Etienne. Meanwhile, Werner Pfennig is an orphan and mechanical savant in a desolate German mining colony, spending days collecting odds and ends to improve upon a radio receiver he’s built and doting on his younger sister Jutta. Marie-Laure’s and Werner’s fates are changed when forced from the safety of their lives and childhood, and each sets out on paths that promise to converge.

What compels us to read war novels? Unless it’s a war with zombies or an alien planet, we know the outcome. It’s those smaller stories that draw readers in, the intersecting lives of victims and perpetrators such as Marie-Laure and Werner, whose possibilities know no bounds.

And it’s the language. In the capable hands of Doerr, even the ugliness and despair of war become poetic. Within the stories of those caught up in the machine, there shines through, like light through a keyhole, an element of hope. — Richard J. Alley

The Mockingbird Next Door: Life With Harper Lee

By Marja Mills

Penguin, 304 pp., $17 (paper)

After decades of eschewing the media, except the seemingly obligatory interview with Oprah (and that in the form of a letter), Pulitzer Prize-winner Harper Lee is as closely associated with myth and mystery as she is with illuminating prose. Chicago-based reporter-turned-author Marja (pronounced MAR-ee-uh) Mills had the opportunity to penetrate some of that mystery when she lived next door to the author, known as Nelle to her friends and relatives, and her sister, Alice Finch Lee, for 18 months from 2004 to 2006. What resulted was Mills’ first book, The Mockingbird Next Door: Life with Harper Lee, a memoir capturing how such an experience came about and the many car drives, cups of McDonald’s coffee, and even honored silences Mills shared with the Lee sisters.

The book is filled with insights about how the Lees lived (Alice since passed away last November at the age of 103): a house covered in books (the sisters gobbled up English history); Harper relishing fishing and sawmill gravy; and long drives on the backroads of Monroe County, Alabama, the sisters’ preferred form of entertainment. I particularly enjoyed learning that they corresponded by fax due to their collective hearing loss and the very human description of Harper’s response to their discussion of Gregory Peck (“Isn’t he delicious?”). Mills even attempts to answer the communal question of why Harper never published again after writing To Kill a Mockingbird:

“When you start at the top, [Harper Lee] told those close to her, there is nowhere to go but down …. But the decision not to publish again was far more gradual than that … I learned that, rather than a grand decision, the shape of her life was dictated by a series of small choices made at different points along the way.”

As a matter of fact, Lee is publishing again. On July 14th, the novel Go Set a Watchman will be available to the legions of undernourished Lee fans. As with nearly anything associated with Lee — including Mills’ memoir — mystery and controversy surround the publication of the book, which was written before To Kill a Mockingbird was published. Some say Lee’s attorney is taking advantage of the author’s failing health — she suffered a stroke in 2007. Mills said, when she was in Memphis recently, that she “share[s] in those concerns,” but she is also “so excited about the prospect of knowing what Scout had to say about her hometown after returning from New York. We get more of Harper Lee’s lovely prose to savor.”

I agree. Great timing, then, to read The Mockingbird Next Door, which is now in paperback and offers some revelations about the enigmatic author just before the curtain again is lifted. — Lesley Young

The World’s Largest Man: A Memoir

By Harrison Scott Key

HarperCollins, 329 pp., $26.99

How large was Harrison Scott Key’s father? If you need a visual aid to enhance your enjoyment of The World’s Largest Man, Key’s tender, sometimes troubling, and drop-the-book-funny memoir, the author has helpfully posted a photograph on his Facebook page.

It shows the book’s title subject posed like a cowboy or a Confederate soldier or maybe just a big guy on horseback behind a barbed-wire fence. Were it a Carroll Cloar painting, the image might be titled My Father Was as Big as a Horse. Unlike Cloar’s famous visual comparison of his father to a tree, this isn’t a trick of perspective, however. Key’s father was evidently large. But Key’s perpetual coming-of-age story is all about the magic of changing perspectives. It’s less about his father’s height and weight than the impressive shadow he cast over everything that mattered to a curious, bookish boy growing up in the American South, where being a big man means something and where size may be greatly enhanced by one’s ability to kill tasty woodland creatures.

Key was born in Memphis, but his impenetrable, Everest-like father moved the family to Mississippi, because he was mistrustful of soft city ways, sidewalks, and such. The father liked shooting things, flirting (a little too graphically) with waitresses, not talking about his feelings, coaching baseball, and gutting the things he shoots. The son liked bow ties and the theater. And he dreaded the first day of deer season when he was “statistically most likely to disappoint” his dad.

The World’s Largest Man is a tone-perfect, gore-spattered meditation on the most tedious human inevitability — that no matter how unlikely it seems, we become our parents. Key’s superpower as a memoirist stems from his ability to effortlessly mingle Erma Bombeck-like takes on potty training with honest accounts of race and class and gruesome Faulkneresque hunting imagery.

After several failed attempts to kill anything larger than a bird, the younger Key eventually shoots his first doe. But, in the book’s most arresting sequence, it’s the author’s description of a second casualty that sticks.

As an adult writer, an academic (Key teaches at the Savannah College of Art and Design), a husband, and a father far removed from the sporting life he lived as a child, Key begins to notice the ways he’s become like his dad. Scenes from his cooling marriage play out as dangerously as scenes in the woods and are presented with a similar mix of comedy and horror.

“The word divorce came up a few times over the next week,” he writes, as work gets in the way of love. “Not in the form of a threat, but just a grenade, a pin pulled on a word to see what would happen.”

Good stuff. — Chris Davis

Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times, Volume 2

Edited by Beverly Greene Bond and Sarah Wilkerson Freeman

University of Georgia Press, 425 pp., $34.95 (paper)

Tennessee Women of Vision and Courage

Edited by Charlotte Crawford and Ruth Johnson Smiley

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 206 pp., $16.99 (paper)

In a society whose innate diversities are only just beginning to receive their full due, it is a remarkable fact that women, who, now as ever before, constitute half the human species, are that proverbial subject whose surface has hardly been scratched. It is even more remarkable that a two-volume series titled Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times should transcend the parochial and, in its collection of historical essays, go far toward illuminating the undiscovered side of that history in a more complete and universal sense than almost any other account yet published, including some vastly more famous and ambitious ones.

Volume 2 has a somewhat broader canvas than Volume 1, published in 2009, which approached its subject via a series of biographical profiles of distinguished women — including the still-active social pioneer Jocelyn Dan Wurzburg of Memphis — whose lives both reflected and influenced important historical circumstances in the Volunteer State from colonial times onward. Volume 2 of Tennessee Women, newly off the press, focuses less on individual lives and more on analytical examinations of the processes and events of history, while continuing to underscore the experience of women, and Tennessee women in particular, and their roles in the creation of that history. As was the case in the previous volume, each chapter is written by a woman, and all the authors have clearly done their homework.

Editors Beverly Greene Bond (of the University of Memphis) and Sarah Wilkerson Freeman (of Arkansas State University) have taken pains to make sure new ground is plowed. The very chapter titles of Volume 2 suggest not only the variety of subject matter but their often stunning originality. Here is a sampling:

“Graceless Yankee Tramps and Secesh She-Devils: Union Soldiers and Confederate Women in Middle Tennessee”; “On Parade: Race, Gender and Imagery in the Memphis Mardi Gras, Cotton Carnival, and Cotton Makers’ Jubilee”; and “Progressive Era Roots of Highlander Folk School.”

Although the contents of this volume are by, of, and for women, they are ultimately for men as well, and indeed are deserving of a cross-cultural audience of the widest possible kind.

A similarly named volume, published in 2013 with no fanfare and available through online booksellers or at the Book Juggler on South Main, pursued a similar mission and is also worth a look. Titled Tennessee Women of Vision and Courage, it, too, is a collection of essays by women and was edited by Charlotte Crawford and Ruth Johnson Smiley, co-directors of the Tennessee Woman Project. Like Volume 1 of the aforementioned series, this volume chronicles the lives of influential women who had importance in Tennessee history in general and in the struggle of women for equality in particular. Two essays, “Tennessee’s Superb Suffragists” by activist Paul F. Casey and “Carol Lynn Gilmer Yellin: Conscience of the Mid-South” by recently retired University of Memphis professor Janann Sherman, are by Memphians who each had a role in the publication of the classic 1998 volume, The Perfect 36: Tennessee Delivers Woman Suffrage — Sherman as co-author with her subject here, the late Yellin, and Casey as a sponsor of the volume and author of a foreword. — Jackson Baker

Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey

By Reid Mitenbuler

Viking, 310 pp., $27.95

Bourbon was born on the American frontier, survived the Civil War and Prohibition, and is now seeing a brand-new life in the small-batch, craft distilleries popping up across the country.

Reid Mitenbuler craftily tells this whole story in his new book, Bourbon Empire. But Mitenbuler tells the whole truth, straying from the burnished images that Jim Beam, Maker’s Mark, and other brands would want us to believe.

In fact, Mitenbuler writes that even its reputation as America’s “native spirit” may be akin to other American legends. He opens his book with an honest look at where bourbon won this well-established superlative, and that sets the tone for the rest of his book and bourbon’s sometimes sketchy past.

Bourbon makers sat on a glut of the stuff after the Korean War and needed help to offload it. They turned to the U.S. Congress, which passed a resolution that called bourbon a “distinctive product of the United States.” Bourbon makers took it upon themselves and wasted no time punching up the dry legalese, calling bourbon “America’s Native Spirit” and labeling the resolution “the Declaration of Independence of bourbon.”

Mitenbuler is a fan of micro-histories like Mark Kurlansky’s Cod and Salt and had begun “geeking out” on bourbon in 2000. His book plumbs bourbon’s well through early-American history to the present. Along the way, he says, people have been attracted to bourbon because it’s rough around the edges, simple, and unpretentious. “The book explores some pretty hilarious attempts on the part of distillers to upgrade bourbon’s image to cut into luxury markets,” Mitenbuler has said.

All of it, from tales of the Whiskey Rebellion to Jim Beam’s “hillbilly heritage,” makes Bourbon Empire great for history junkies and bourbon aficionados alike. — Toby Sells

Southern Cooking for Company

By Nicki Pendleton Wood

Thomas Nelson Books, 279 pp., $26.99

“Where would a Southern party be without … soft, sweet, mustardy, buttery, speckled ham rolls?”

Where indeed! Such are the questions posed in Nicki Pendleton Wood’s Southern Cooking for Company, a fine compendium of recipes and tips from 100-plus notable party-givers and hosts from around the South.

Another question: “There’s nothing sadder than a skimpy-looking pie, is there?”

The solution is to choose the right size pie dish — you won’t want to mess up Betsy Watts Koch’s Praline Pumpkin Pie.

More tips:

1) Don’t stress. Let the guests serve themselves and help clean up. Deanna Larson’s Collards with Citrus and Cranberries looks relatively carefree with minimal ingredients and chopping required.

2) Nothing beats a well-planned breakfast spread, and no one would argue with Renee Flynn’s classic Baked French Toast.

3) Host a holiday leftovers party. It is what it sounds like. Guests bring their leftovers or something made with the pounds of turkey and other holiday scraps. Make note of Anna Ginsberg’s Turkey Poblano Soup.

Nicki Pendleton Wood is a food-writing vet based in Nashville, and she’s produced a thoughtful book. Its recipes are not overly complicated, but neither are they ordinary. The Pimento Cheese Pinwheels and Beet Pickled Devilish Eggs are sure to turn heads.

Overall, a useful weapon to have in any cook’s arsenal. — Susan Ellis

Slab

By Selah Saterstrom

Coffee House Press, 186 pp.,

$16.95 (paper)

If asked to describe Slab in one sentence, it would go something like this: a novel about the life of one woman, nicknamed Tiger, from a poor area of Mississippi and following the turmoil of Hurricane Katrina. But what an oversimplification that would be.

Slab, by Selah Saterstrom (director of the Ph.D. program in creative writing at the University of Denver), is not told in a traditional style. It is in the form of a play with two acts organized by scenes of varying length. However, the majority of the story is in the form of a monologue. The many stories laced throughout are occasionally broken up by Tiger talking with Barbara Walters. Whether Tiger is actually speaking to Walters or the entire story is being conducted in her head is never made clear.

Who is Tiger? She is an ex-stripper with a family history filled with turmoil and bad decisions. This is not a book about a troubled girl with a happy ending. It is the story of a girl who misunderstands a lot of the world as told through her many adventures and mistakes with men. A number of those stories are about her friends and experiences in Mississippi, but despite all of the difficulties she faces, Tiger seems to find her own path.

The book is shocking at times and often brings up questions that are deeper than the comical nature of some of the tales, such as, “Do you believe in life after death?” While answers to profound questions such as this are not to be found in Slab‘s stories of sex and drugs or loss and longing, there is meaning to be taken from Slab. You simply have to find it in your own way, just as Tiger does. — Alaina Getzenberg

The Breaking Point

By Jefferson Bass

William Morrow, 367 pp., $26.99

I should have been a homicide detective. Every weekend, I spend all of my spare moments listening to Forensic Files marathons on the HLN channel on satellite radio. I’m kind of obsessed with murder (but only in a whodunit way), and I’m also pretty intrigued by the science of what happens to rotting corpses.

So I was thrilled when I learned there’s a series of crime novels based on and around the UT-Knoxville Forensic Anthropology Center, better known as the Body Farm. The novels are crafted by the writing team of Jon Jefferson and Dr. Bill Bass (the real-life creator of the Body Farm, where the decomposition of donated corpses is scientifically studied), so together they go by “Jefferson Bass.” The protagonist is a fictional character, Dr. Bill Brockton, based on Bill Bass.

The team’s latest novel, The Breaking Point, has all the things I need in a crime novel — the mysterious death of a maverick millionaire, the subsequent investigation, a little subplot about the protagonist’s crumbling personal life, and a few nosy TV reporters to muck things up.

The book opens with the airplane-crash death of Richard Janus, the super-wealthy founder of a nonprofit international aid organization. At first, it appears to be an accident, but Dr. Brockton (who assists the FBI at the crash site) and the team slowly uncover details that have the potential to turn the case into a homicide investigation.

Since the novel is co-written by Bill Bass, a world-renowned forensic anthropologist, the prose about the investigation is incredibly detailed. It gave me the sense of being right there, uncovering bits of skull and teeth right along with the detectives. But the plot isn’t all work and no play. There’s plenty going on that reveals Brockton’s personal side, too. And there’s a subplot that has Brockton coming up against reporters concerning what some see as desecration of the dead in his work at the Body Farm.

My biggest complaint? I wanted more trash talk from the detectives in the field. At one point, Brockton is cautioned about his language before he even utters a curse word. Come on! Also, because the book is part of a series, there’s some back story about the Brockton family’s past run-in with a serial killer, which fell a little flat for me. I needed more context, but I suppose I should start the series from the beginning. And given my interest in the macabre, I probably will. — Bianca Phillips

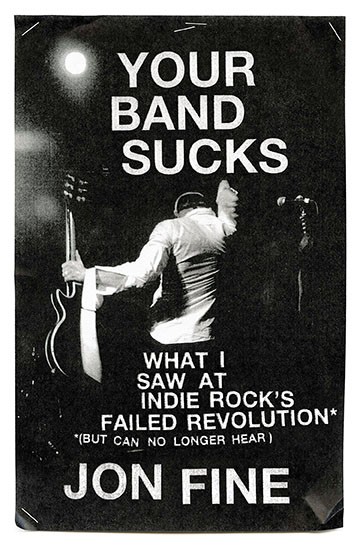

Your Band Sucks: What I Saw at Indie Rock’s Failed Revolution (But Can No Longer Hear)

By Jon Fine

Viking, 320 pp., $27.95

Jon Fine went in the opposite direction of Michael Azerrad’s cult-classic Our Band Could Be Your Life when he chose the title Your Band Sucks for his new book, but at least the name might jump out at potential buyers.

Your Band Sucks is the story of Fine’s involvement with underground music, from his days attending battle-of-the-bands concerts in suburban New Jersey to his time spent playing in indie rock bands like Bitch Magnet, Coptic Light, and Vineland. The fact that you’ve probably never heard of any of those bands seems to be the underlying theme of Your Band Sucks, in the sense that during those early, “we can change the world” days of ’90s indie rock, you didn’t have to be called Nirvana to tour the United States.

By being on the front lines of the birth of indie rock, Fine is able to give a firsthand account of what it was like touring in the days before the internet — a time when word of mouth, college radio, and tiny record stores were all that bands had to help them network a tour.

The book is thorough in its attempt to document what it really was like for bands of Bitch Magnet’s size (or smaller) to navigate the U.S. tour circuit, but like many rock-and-roll documents, an air exists that this was “the end of rock’s glory days.” In fact, the inside jacket of Your Band Sucks claims that Fine has captured, perhaps, the last moment when rock music still mattered. This type of proclamation reeks of the “punk is dead” mentality, a phrase that gets laughed at by the thousands of current underground/indie bands still touring and making records off the support of college radio, word of mouth, and tiny record stores. — Chris Shaw