- JB

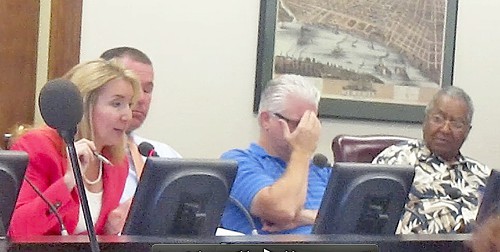

- Commissioners Heidi Shafer, Wyatt Bunker, Chris Thomas, and Sidney Chism in the throes

In yet another of a series of stormy, divided sessions on Wednesday, the Shelby County Commission, with 12 of its 13 members meeting in budget and finance committee, failed once again to agree on a tax rate for fiscal 2013-14.

As a consequence, the $1.2 billion budget agreed to on June 3 remains in limbo, with funds frozen for a variety of programs and with the new Shelby County Unified School System — formally, as of July 1, a complete entity — remaining unfunded, its future more uncertain than ever.

For at least the coming school year, the system will contain all the public schools of Shelby County, city and suburban alike. But the county’s six suburban municipalities — Germantown, Collierville, Bartlett, Arlington, Lakeland, and Millington — voted overwhelmingly on Tuesday to establish independent municipal school systems.

It was essentially a rerun of 2012, when the six suburbs voted for their own school systems, but the legislation enabling that vote had restricted the lifting of a ban on new special school districts to Shelby County, and U.S. District Judge Hardy Mays found the resulting law unconstitutional. A new measure in 2013 lifted the ban statewide and seems to have passed judicial muster.

Along with that first abortive vote in 2012 the six suburbs had also voted to assess themselves a half-cent sales tax to pay for the new schools, which they now hope to open in August 2014.

The revenues from those taxes remain in escrow for the time being, and Henri Brooks, an outspoken commission Democrat and veteran of the Tennessee House, insisted again on Wednesday, as she has before, that the suburbs should free up some of that money to help defray the costs of the unified district for at least the next year, since their students will be served by it. “Get some skin in the game,” she said, sardonically echoing a phrase used earlier by Republican commissioner Terry Roland of Millington.

The equally outspoken Roland retorted that the suburbs might consider the point if the commission should drop its continuing lawsuit against the municipalities’ effort to establish independent school districts. The major remaining issue is whether the new systems would foster re-segregation, as argued in the still ongoing legal action supported by the commission’s 7 Democrats and Republican chairman Mike Ritz.

(Other outstanding issues are: the conditions under which the suburban school districts might acquire title to existing school buildings, as well as which district or districts get to serve students in outlying unincorporated areas.)

Both Brooks and Roland may have a point — a fact that doesn’t, however, mean that agreement on the point is remotely near.

SHELBY COUNTY MAYOR MARK LUTTRELL, a Republican, has proposed a $4.38 tax rate, and that amount was approved on first reading, along with the budget, on June 3. Since then, however, there have been defections among commission Democrats, and, when the tax rate proposal came up for its third and final reading last week, it failed by two votes — those of previously supportive Democrats Justin Ford and James Harvey, the latter of whom ended up as chairman-elect, with votes from Republican tax-rate opponents enhancing what had been his dark-horse prospects.

Luttrell’s budget proposal began with a 30-cent increase from the current $4.02 tax rate merely to get to the level of the new certified tax rate of $4.32, based on drastically lowered overall property-value assessments in the most recent appraisal.

For non-initiates, the state-established certified tax rate is that which guarantees annual revenues equivalent to those raised under the prior rate. The hugeness of that 30-cent factor not only made good rhetorical fodder for tax-rate opponents, it demonstrated how precipitately local property values had dropped.

Beyond the certified-rate level, the mayor added another 6 cents to account for what all (or virtually all) parties seem to agree is a bare-bones budget for the hard-pressed new school district. Estimates of the additional revenue raised by those 6 cents go as high as $20 million, though some opinions posit a lower figure.

After the failure last week to approve the $4.38 rate, there was optimism and some advance indication that Wednesday’s meeting would see a coalescing around the certified rate figure of $4.32. Indeed, preliminary head counts pointed in that direction.

The $4.32 figure, said Luttrell and his aides, would necessitate a loss of $9.6 million in potential revenue from his requested $4.38 figure and would mean cutting jobs and programs. But it looked like a potential compromise figure.

When Wednesday came, it was Roland, previously a diehard opponent of any tax increase, who surprisingly made a proposal for the $4.32 rate (that being the circumstance for his everybody-put-skin-in-the game plea), and, either because the brash Millingtonian was too controversial a sponsor or because various commissioners had second thoughts, that proposal garnered only two votes.

Roland, a prototypical come-on-hard type, has gone out of his way to antagonize several of his colleagues, and it may have cost him on Wednesday. Though introductory remarks Monday by chairman Mike Ritz seemingly had cleared the way for a $4.32 outcome, Roland may have been the wrong messenger. In any case, he would soon be buffaloed by adverse reaction to his proposal from Democrats Melvin Burgess and Walter Bailey.

Budget chairman Burgess is one of two colleagues (the other is Sidney Chism) whose potential enthusiasm for a tax increase Roland had attempted to check in advance by raising conflict-of-interest questions about their benefiting, directly or indirectly, from county funds.

Chism, owner of a day-care center that receives some wrap-around funds, has been abstaining throughout the tax-rate debate. But Burgess, a school system employee, has been defiant about what he called “bullying” (though it may have restrained him, as chairman pro tem, from seeking the chairmanship), and he vehemently took issue with Roland.

“We don’t have a plan,” he said, by way of characterizing Roland’s proposal. He further referred to it as a case of “wake up in the morning, come up with some numbers, and ask the administration to go and cut.” He concluded, “I’m not supporting this today.”

Bailey was even more blunt, though he seemed to be addressing the commission’s other conservatives more than Roland when he slung together a philippic containing terms like “whimsicalness… capriciousness… bordering on irresponsibility… armchair pundits… pander… utter nonsense… disservice.”

Bailey said no to $4.32 as well, even though an aggrieved Roland made a point of offering concessions. He agreed with Burgess and his fellow conservative Heidi Shafer that the schools should probably not be penalized.

Thus, while the first version of his plan had evenly distributed the nut-cutting between the schools and the county’s general fund, Roland amended his proposal, which envisioned taking $5 million in one-time-only money from the county’s $20 million reserve fund to start with, and suggested the whole of the remaining $4.6 million in reductions could come from the general fund.

“I’m trying to extend the olive branch,” said Roland. “At the end of the day I love each and every one of y’all to death. Like my grandma would say, ‘I love you but sometimes I don’t like you.’” Criticism of his plan, which “hurts my feelings,” amounted to so much “Monday morning quarterbacking,” he said “We’ve got to come together to find common ground.”

He defended his basic plan against Burgess’ charge that it was a hastily improvised wake-up-in-the-morning affair, insisting that he and Shafer had spent several of the preceding days in the commission and mayoral offices toiling over options (“me, too,” Harvey would later note), but, in the end, both of the two variants Roland offered came to naught.

“Forgive me for trying to compromise,” Roland said bitterly. “It didn’t work. It’s either all or none.” And he would later return to making common cause with the GOP hard-core on the commission.

AGREEMENT ON A COUNTY TAX RATE is complicated by the fact that a minority of GOP conservatives on the commission — Wyatt Bunker, Chris Thomas, Shafer, and, until Wednesday, Roland — have been reluctant to extend the existing $4.02 tax rate at all, contending that the budget is being balanced on the taxpayers’ backs, as always before, and that maybe the time has finally come for serious downsizing of county government.

Bunker was vehement to the point of intractability. “This is not a time to compromise, it’s a time to stand strong,” he said, maintaining it was “not my job” to puzzle out specific cuts. That was up to the administration. “My job is to tell you what people can and can’t afford.” What he demanded was “a balanced budget with cuts that are appropriate to this county.”

A piece of financial accounting accepted by everyone is that, at the certified tax rate of $4.32 (which, even after the battering it took on Wednesday, remains a possible compromise figure), 73 percent of the county‘s taxpaying population would see lower taxes, while taxes for the remainder would either remain level or increase. Businesses, especially, would see dramatic increases, say the dissenters.

Looking ahead to the next public commission meeting on Monday, word is beginning to circulate again that Luttrell may have been persuasive enough in his insistence on his original $4.38 rate as a rock-bottom necessity that the two fall-away Democrats might return to the fold and approve that original figure.

Or not. And, if not, the commission has to face up to the fact that the fiscal year is already underway and that funds are already being spent on the basis of the pre-approved budget. Meanwhile, as the waiting game continues, various programs and grants are in a state of freeze, and the schools, priming to open within the month, worry about where their operating money is going to come from.

- JB

- Never Say Die — Grants are frozen until a tax rate is declared, but advocate for homeless services Brad Watkins makes the case anyway.