This year, Millennials are expected to surpass Baby Boomers as the largest living American generation, and soon, their effects on the economy will be felt in greater measure, according to a new Standard & Poor’s report.

The report, by Beth Ann Bovino, Standard & Poor’s U.S. chief economist, noted that the generation born from 1981 to 1997 numbers 80 million and that they spend an annual $600 billion. By 2020, they could account for $1.4 trillion in spending, or 30 percent of total retail sales.

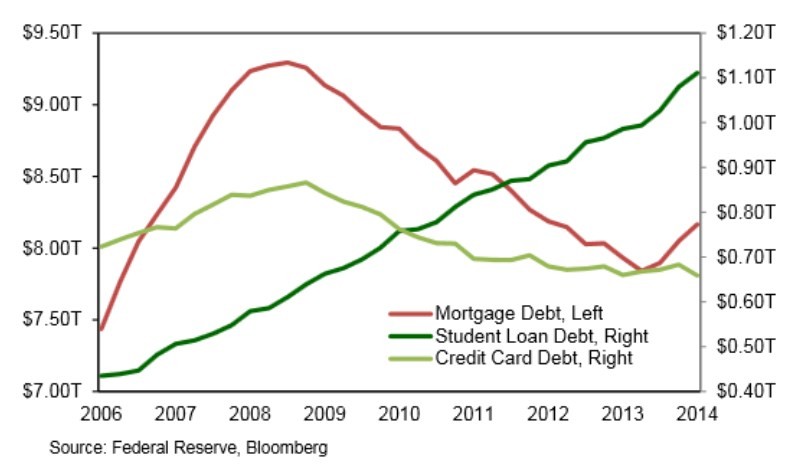

Surprisingly though, this generation has conservative spending habits, similar to those of the Silent Generation, which grew up during and after the Great Depression. What distinguishes Millennials from other generations is the historic student loan debt that they carry, which in turn has meant that Millennials have had less access to full-time jobs and wealth.

Bovine looked at how what this generation might do over the next five years might affect the U.S. economy. If the economy continues to strengthen, as Standard & Poor’s projects, there’s potential that Millennials could start making big-ticket purchases that contribute to economic growth. On the other hand, their student loan debt could keep them from spending and not buying houses, costing the economy.

“Millennials are going to be making up half the workforce in just five years. They’re already the largest cohort of American workers,” Bovino says. “That’s why some of their characteristics — marrying and having children later, renting instead of buying a home, preferring to live in cities and not own cars — could disrupt the U.S. economy. Two-thirds of GDP is consumption, so we rely on people spending money.”

The biggest difference between the Silent Generation and Millennials is the latter group’s record student loan debt. Adjusting for inflation, current borrowers have to pay back about twice as much as borrowers from 20 years ago. In 1989, the bottom three-fifths of Americans aged 18-34 had an average net worth of $3,300. In 2013, that same group had a net debt of $7,700.

That debt burden can force Millennials into taking jobs they don’t want, or settling for jobs they wouldn’t have considered in a better market. It takes at least 15 years for workers who start their careers in a recession to make up for the decrease in earnings that they experience compared to people who enter the job market at a time of economic prosperity.

On the other hand, Millennials are the most educated generation, so Bovino believes that their career success has been delayed, not canceled. Wages are projected to pick up to 3 percent this year. Since workers with a college degree generally earn double what those with a high school degree make, Millennials may soon have more earning power.

But housing is the key. If wages don’t pick up through the next decade, Bovino says Millennials would be forced to continue to avoid big purchases such as homes and cars and delay starting families. Bovino estimates that a downside scenario could mean the U.S. GDP would miss out on $49 billion a year through 2019.

Millennials are already forming households at a slower rate than previous generations. The number of 25- to 34-year-olds living in their parents’ homes jumped 17.5 percent from 2007 to 2010. In 1960, three-quarters of women and two-thirds of men were financially independent, had married, and had children by age 30. Even in 2003, a 30-year-old American was twice as likely as a Millennial to own his or her own home.

Another problem is that student loan defaults are worsening. Although Standard & Poor’s doesn’t expect widespread defaults, a significant number of defaults would hurt the country’s finances, since the federal government backs more than 85 percent of student loans.

Despite these challenges, recent signals are good: Job creation and hourly wages are up, with wage increases outpacing inflation. “There’s some momentum in the jobs market and workers have more bargaining power. That’s a strength for Millennials as they continue to participate in the market,” Bovino says.

And Millennials are starting to buy more new cars, having now surpassed Gen-Xers as the second-largest group of buyers.

Bovino expects the economy to continue developing in a way that will allow this generation to “transition into the traditional definition of full adulthood and, in a virtuous circle, begin to buy the houses, cars, and other big-ticket items that will further stimulate economic growth,” she writes.

Laura Shin contributes to Forbes.com and SmartPlanet. Her most recent e-book is The Millennial Game Plan: Career and Money Secrets To Succeed in Today’s World.