August Wilson’s plays are full of love, life and humor, but they all list in the direction of tragedy and his life’s work documents just about everything that went wrong in America during the 20th-Century. Over the course of 9-plays set in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, and one play set inside a Chicago recording studio, Wilson’s wordy wonders celebrate 100-years of African-American achievement, culture and community. Everything is set against the backdrop of Jim Crow, exploitation, segregation, isolation, war, overcriminalization, labor dispute, banking disaster, and the flight of blue collar industry from the urban core. Although it was first produced in 2005, Radio Golf— currently running at the Hattiloo Theatre— even addresses topical issues like police officers shooting unarmed African-Americans, with relative impunity. Radio Golf is set in 1997, making it the last play in the series chronologically. It’s also the last play Wilson wrote before he died. It’s easily the author’s leanest work and his most direct. The story is a heady, Mamet-esque mix of business and politics that looks at a specific kind of gentrification masquerading as urban renewal. It’s primarily a study in class bias and exceptionalism: the public tendency to define minority groups by best and worst examples as determined by a white middle class standard, but widely adopted across the cultural spectrum. Forced to describe the play in one word, “prescient,” might just do the trick.

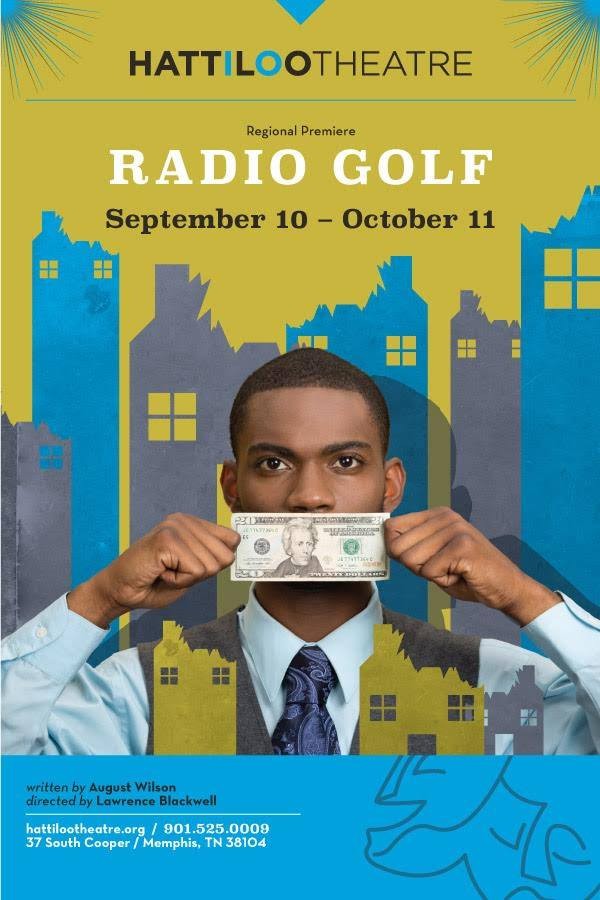

The Hattiloo Stages August Wilson’s Last Play, Radio Golf

In addition to all those other things, Radio Golf is also a good old fashioned Cain and Abel story. Harmond Wilks and Roosevelt Hicks are two old school chums from the “wrong side of town” who got out, got educated, and are now going back and “giving back,” to their down-at-heel community. Their gift will appear in the form of mass demolitions followed by the construction of condos, and an enormous retail development with a Whole Foods. At the top of the play both men are hopeful that the area will be designated as “blight” by the city, so they can qualify for more grants and public aid. Their individual attitudes are about to be adjusted by the people they meet after opening a business office/campaign headquarters in the Hill District.

Roosevelt is a Tiger Woods fan who thinks the kids from his old neighborhood would really benefit from learning how to play golf. He’s done well for himself in the banking world, and is moving into radio station management. He’s also joining the hand-selected team of a successful white developer. The latter partnership gives said developer a minority front and a stake in the Hill district redevelopment. In return Roosevelt gets to spend more money and more time dreaming on the links.

Wilks reluctantly welcomes characters from the neighborhood into his office. He’s awkward and sometimes insulting, but he genuinely wants to employ these hard luck cases, and to engage them in the civic process. He wants to make them believe that they aren’t alone and can make a difference. Sterling Johnson is an ex-con construction worker (originally introduced as a young man in Two Trains Running) and Elder Joseph Barlow is the strange talking man who could stop the retail development in its tracks. These two men represent the neighborhood as it is now, while functioning as ghosts from its past. Over time Wilks hears what the two men are saying, and realizes the degree to which he’s been the victim of pervasive urban narratives regarding everything from blight to the meaning of success. He wants to be everybody’s mayor someday, but the more he tries to do the right thing, the more he’s made to understand how the things he’s required to do to be elected will make him a, “white man’s mayor.”

Roosevelt has no patience for the less fortunate men who drop by his office, and no time for his old friend’s crisis of conscious. When it becomes clear that he and WIlks have acquired Barlow’s property illegally, he dismisses the technicality and moves forward with demolition. And so the tension lines are drawn.

Emmanuel McKinney (Wilks) and Bertram Williams Jr. (Roosevelt) give strong performances as the upwardly mobile partners. They are sometimes eclipsed by Shadeed A. Salim (Barlow) and Willis Green (Johnson), who bring the neighborhood characters to life with tremendous subtlety, understanding, and detail.

Joia Erin Thornton also turns in a solid performance as Mame Wilks, Harmond’s marketing director and wife. She watches her career falter as a result of her husband’s good deeds. As her plans fall apart so does the marriage. What does saving an historic home and the soul of a neighborhood mean if you lose your cushy gig working for the governor?

For its relative brevity, Radio Golf picks up on histories launched in Wilson’s first play Gem of the Ocean, and carried forward throughout the Pittsburgh series. Director Lawrence Blackwell has done a great job pulling all the threads together. As a result, one doesn’t have to be a Wilson scholar to pick up on the backstory. Some familiarity may help.