Ed Perry isn’t famous. He died, a complete unknown, of congestive heart failure in 2007, in the toxic environment of his cluttered home and studio in Stephensport, Kentucky.

“They say he died of congestive heart failure, but there was so much wrong with him you can’t keep up with it all,” says Memphis songwriter Keith Sykes, who met and became close friends with Perry in the 1960s. “Ed was relentlessly cruel to his body his whole life,” Sykes adds.

At the time of his death, Perry’s only source of income was a small Social Security check. He died penniless. All he left behind was a mean parrot named Jake, a filthy house overfilled with furniture parts, old wood, and electronics he’d collected for the creation of future projects. He also left an uncommonly unified body of work, much of which had never been exhibited due to Perry’s deep mistrust of the commercial art world.

Although he despised the gallery system, many of the large, meticulously constructed pieces Perry built, mixing painting and sculpture while skirting the boundaries of fine and folk art, were painstakingly labeled, with notes regarding size, weight, construction and, when appropriate, wiring schematics. Many pieces were boxed and stored, as if awaiting their invitation to gallery shows that were never booked. So they sat for decades, gathering mildew and parrot dung, like dirty brides left waiting at a shabby alter.

“Contaminated” is the word Sykes uses to describe his old friend’s living environment at the time of his death. “He must have worked for two weeks to just make room for us to move around,” he says recalling earlier, happier visits. It fell to Sykes to salvage, store, clean, and painstakingly catalog his friend’s work. “If you were sensitive or had any kind of allergies at all, you probably couldn’t go in there at all,” he says. “We finally got stuff out with masks and gloves on. Because over the years all the nicotine and all the sawdust and all the moisture had conspired together to make it just pretty damn deadly.”

So who was Ed Perry? What is it that sets his work apart from so many other artists who collect their MFAs and never exhibit again? And what did this completely unknown artist do to merit two simultaneous shows of his work at the Memphis College of Art (MCA)?

Judging by his resume and correspondence, Perry self-identified as a “Visual Engineer, MFA,” and an “electro-optics engineer,” whatever those titles may imply. He was also an abstract painter and an obsessive builder. He was a chain smoker, a self-made scientist, and a 1972 Memphis Academy of Arts graduate. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he trained as a figure skater in Lake Placid, New York, where he met and befriended Olympic medalist Peggy Fleming. He was also a radical pacifist, a drinker of strong libations, and a boundary-defying conceptual artist working with found materials, spray paint, and state-of-the-art lasers.

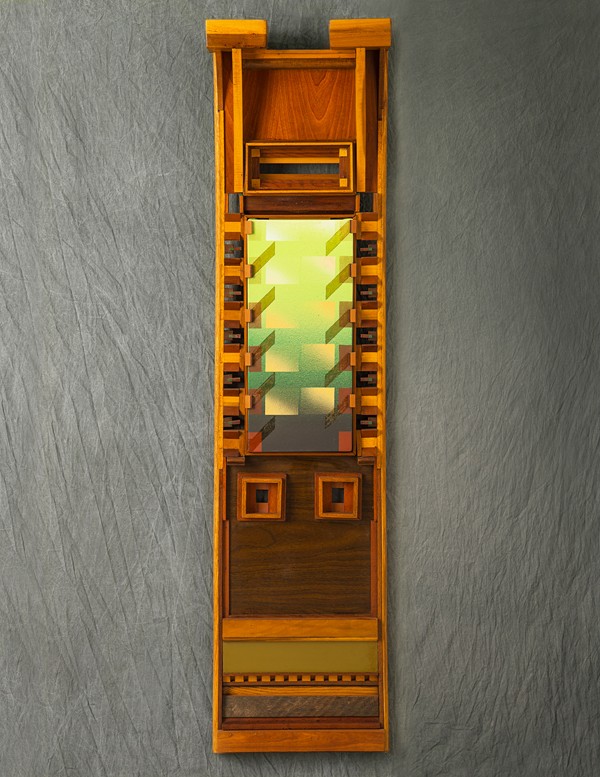

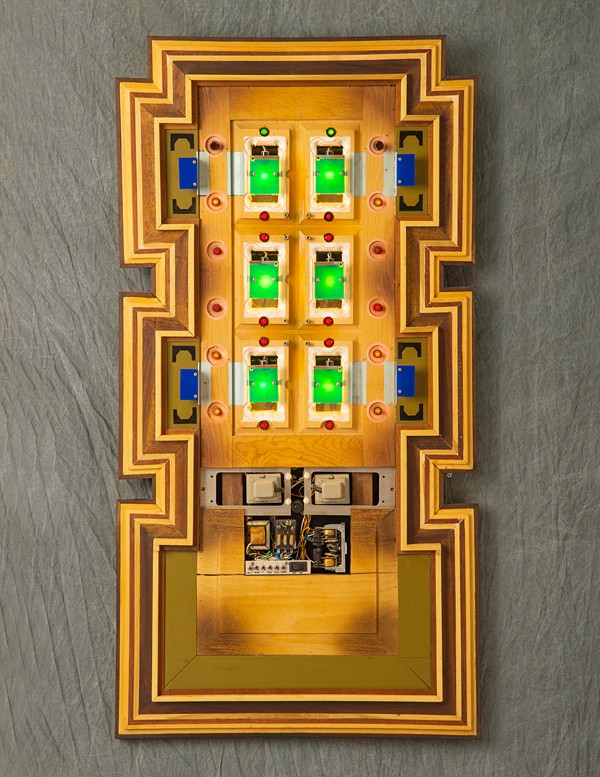

Courtesy of Memphis College of Art

Courtesy of Memphis College of Art

Ed Perry was a Pacifist but became enraged when diplomatic agreements resulted in the destruction of missiles he might have transformed into art supplies.

Additionally, the man collected in “Ed Perry: Constructions,” and “Ed Perry: Between Canvas and Frame,” was something of a stock character: the misunderstood genius, pursued by personal demons, uncompromising to the point of being commercially invisible throughout most of his semi-reclusive lifetime.

Perry was highly trained both as an artist and a laser technician. He shared studio space with groundbreaking artists like Sam Gilliam and frequently worked alongside Washington D.C.-based art star and fellow parrot-owner Rockne Krebs, to create massive, urban-scale laser installations. But he was an artworld nobody when he died in 2007. And it’s unclear just how much the MCA exhibitions can do to launch an unknown alum’s posthumous career, or give his elaborate, mixed-media constructions the happy afterlife Perry’s friends think they deserve.

Remy Miller, MCA’s dean of academic affairs and the driving force behind both Perry exhibits, thinks it’s too easy to sensationalize the lives of troubled artists, and he worries that doing so takes emphasis off of the work. “People tell these horrible stories about a guy who was falling apart and struggling to live,” Miller says, specifically referring to accounts of the life of action painter Jackson Pollock. “That’s really what you want to talk about in the face of this beautiful work?”

But even Miller succumbs somewhat to the temptation of a good story, comparing Perry to Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch painter whose post-mortem success is partly responsible for the enduring myth that nothing increases the value of an artist’s work like a difficult life and untimely death. But the van Gogh story, while relevant in so many ways, isn’t an especially realistic impression of how the modern art world works. Perry despised the business side of art-making, and although his resume lists a handful of shows, for the most part he seems to have actively avoided public viewings of his work.

“I asked him if he’d ever thought about making a coffee table book, and what came out of him was another Ed I didn’t know and didn’t want to know,” Sykes says, recalling a past dustup. “I just wanted people to see the stuff. He really hurt my feelings over that.”

“I think Ed understood the work was really good,” Miller says. “Why else prepare all of that other stuff? Why bother to box it up? Why keep it? Write all those notes on it? I think Ed just couldn’t bear to sit through what was going to have to happen next.”

Gordon Alexander shared a house with Perry when the two were still students at the Memphis Art Academy (now MCA). He remembers a visit from his friend some years ago, on the night before several larger pieces of Perry’s work were scheduled to ship to Memphis’ Alice Bingham Gallery for a show. “Ed just says, ‘I’m not going to do it,’ and he didn’t. And that was it.” The pieces never shipped; the show never happened.

In some regards, because he has no exhibition history or records of previous gallery sales, Perry might as well not exist. He has no place within the established art world. And even if gallery people find the work compelling, they don’t really know what to do with it, because there’s no previously established value.

“It’s a kind of catch-22,” says Ellen Daugherty, the art historian who led an MCA class on Perry and contributed an essay to the exhibit’s striking catalog.

Art consultant John Weeden was enlisted to structure a logical value scale for Perry’s work. He couldn’t discuss the specific rubric, but he gave a general overview of how we might assess the worth of artwork created by a previously unknown artist.

“Commercial history and provenance are two of the leading factors in determining the general value of an artwork,” he says. “In the case of a largely unknown artist, the task becomes one of establishing a framework upon which an initial market for that artist’s work may be constructed.” Weeden also allows other considerations including the nature of the materials, the style of the pieces, the reputation of the artist, and the level of craftsmanship, labor, and design.

So finally, with two shows, a class, this story, and any other attendant press, Perry the artist finally has a public paper trail. His working relationship as an artistic and technical assistant to Krebs can be affirmed, and too late, maybe, an underappreciated artist gets his overdue recognition.

MCA’s Miller doesn’t equivocate: “I wouldn’t be talking to you right now if I didn’t think that this body of work can stand up next to any body of work created in the later half of the 20th century,” he says. “I absolutely believe it’s as good as any body of that work made by any artist during that time period.” Miller’s not alone in that belief. Sykes and Alexander, both close to Perry since the 1960s, have made a strong effort to ensure that their old friend’s life work doesn’t pass unnoticed.

Perry was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky. His father was a WWII vet. His brother Bill also went military. Perry, on the other hand, took classes at community college and trained as an ice skater before leaving for art school in Memphis in the fall of 1967. He was riding a Triumph motorcycle and wearing a flak jacket and WWII combat helmet the first time Alexander saw him pulling up to the Memphis Art Academy in Overton Park. The two young artists bonded early, becoming neighbors, first in the Auburndale Apartments, then housemates, when they moved, along with their friend Paul Mitchell, into an old house on Madison Avenue where Overton Square’s French Quarter Inn now stands.

By most accounts Perry was a good but not stellar student who worked hard when he was interested and sometimes flummoxed faculty. He would eventually become MCA’s student body president.

“I was in New York by then,” Alexander says, speculating that his friend must have been drafted into student government. “He hated titles.”

Always interested in technology, especially the artistic applications of lasers, Perry also took physics classes at Rhodes College (then Southwestern).

Alexander describes the Memphis Art Academy as being a creatively fertile environment and speculates that Perry was especially influenced by the work of three notable professors: Ted Faiers, who experimented with totemic “Indian Space” painting and 3D painting; Ron Pekar, the original graphic designer for Ardent Studios who worked in neon and designed the logo for Big Star’s #1 Record; and acclaimed color theorist Burton Callicott, who painted false shadows in his work and created colorfields that seemed to glow with their own internal light. Because he was exposed to so much 20th-century art, it’s difficult to call out specific influences, but it’s not difficult to look at Perry’s totem-like constructions and imagine all the ways they might be inspired by these mentors.

Alexander describes the house he shared with Perry as a mattress-on-the-floor den for starving artists. Work was always being made by someone somewhere in the house and painters, sculptors, and musicians were always coming and going.

“We didn’t even lock the house,” Alexander says. “I know it’s hard to believe, but it’s true.” Musician and occasional actor Larry Raspberry was an intermittent visitor. So was Sykes and a young Alex Chilton, who would eventually move in next door. Somebody was always playing music. When they weren’t, Alexander, an audiophile and music editor for the then-Dixie Flyer, Memphis’ original underground newspaper, was spinning records on the turntable.

It would be years before Sykes would co-write the hit song “Volcano” and hook up with Jimmy Buffett’s Coral Reefer Band. At this point he hitchhiked, pumped gas, worked the holiday rush at Sears Crosstown, and toured as a Dylan-inspired folkie on the Holiday Inn Circuit. He met Perry and Alexander when they were still living at the Auburndale Apartments and remembers being smitten by Ed’s work from the very beginning.

“Once you see an Ed Perry, you’ll always know his work,” Sykes says.

Like so many great college friends, Sykes and Alexander became separated and immersed in their own families and careers. They lost touch with Perry for 20 years.

Perry took his MFA at the University of Cincinnati, where he subsequently went to work for Leon Goldman, a dermatologist and laser surgery pioneer sometimes referred to as “the father of laser surgery.” Perry and Goldman co-created studies on laser surgery and published them in scientific journals. But when it was time to make art again, Perry moved on.

Krebs met Perry in 1974 at a laser safety certification class at the University of Cincinnati and almost immediately hired him as an art assistant with laser-safety training and advanced technical skills. This was the beginning of a decade-long working relationship with Krebs.

Perry eventually moved to D.C., where he kept an apartment and studio on the second floor of a warehouse co-owned by Krebs and noted color field painter Gilliam who, like Faiers, had been painting well beyond the frame.

Krebs had a cranky parrot named Euclid, and Perry acquired a cranky parrot named Jake. Studio visitors sometimes had to use trash can lids as shields to avoid a ferocious pecking.

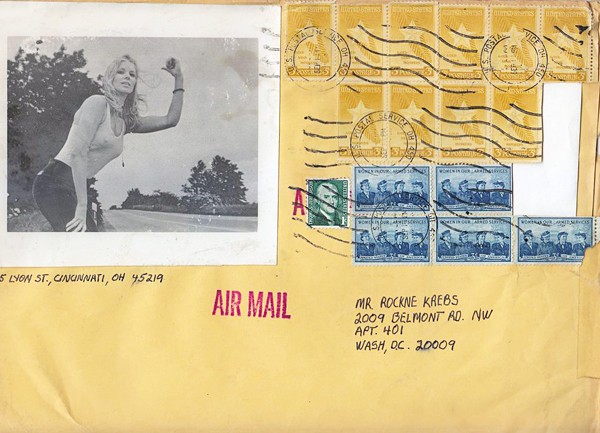

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

Heather Krebs, Rockne’s daughter, remembers Perry well. She says she had to pass by his studio whenever she visited her father’s. “He was always in there working,” she says, remembering his creations, like the decorated envelopes he made for her to use, but which she kept instead.

Heather suggests that Perry might have benefitted from his proximity to both her father and Gilliam. Clients coming in and out would have seen his work in Krebs’ studio or in his own. She wonders if steady work meant he didn’t feel pressured to show.

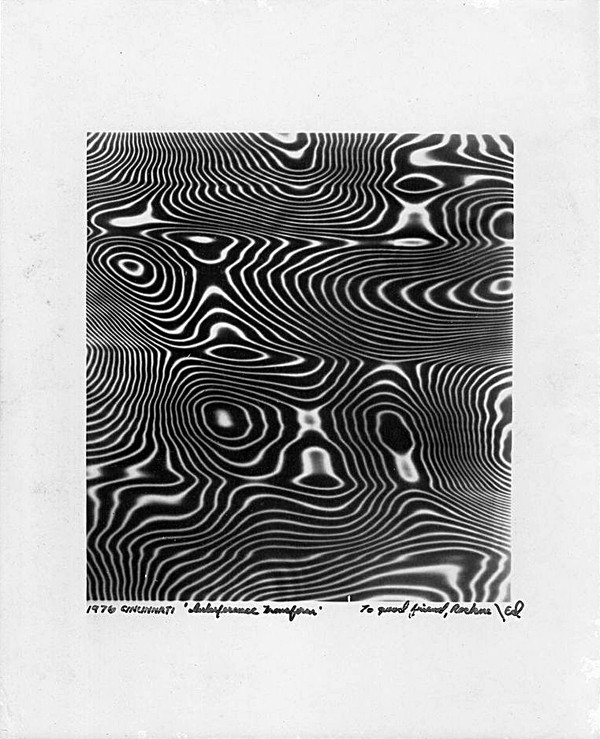

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

Ed Perry and Rockne Krebs unload one of their urban-scale installations

Krebs created large-scale laser and solar installations for the Omni International Building, now the CNN Center, and Perry consulted and assisted. “Omni was billed as the greatest premiere in Atlanta since Gone With the Wind,” Perry wrote excitedly to Krebs, describing the 1976 opening.

“The stuff shirts oohed when Tony Orlando took the microphone,” Perry continued in his letter. “And moaned when he announced he would not sing.”

Perry moved back to his parents’ farm sometime around 1986, and that is where he either built or completed many of the constructions on display in “Between Canvas and Frame.”

Ellen Daugherty thinks that, for all of his training and expertise, Perry’s work sometimes resembles folk art. “Ed builds this stuff that has a kind of similarity to some folk artists,” she says, citing his approach to construction and his use of available, affordable materials like old fence boards and discarded Shaker furniture parts. “But when you look at the stuff, that ain’t folk art,” she says. “It’s highly trained. And extremely visual and abstract.”

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

Courtesy of Rockne Krebs Estate

A laser diffraction photo by Ed Perry given to laser artist Rockne Krebs

The backs of Perry’s constructions are often as lively as the fronts. Electronic pieces include a full-sized drawing of the wiring plot. Many pieces include obsessive notes about what kinds of materials have been used, when the canvas was primed, and so on. He also makes diary entries marking everything from Halley’s Comet arriving in conjunction with the first Martin Luther King Jr. Day, to notes about the Mississippi River flood of 1993.

The two Perry shows are the culmination of a sprawling buddy adventure that launched in Midtown in the 1960s and is now coming home to roost.

“In the late 1990s me and Gordon started talking,” Sykes says. “We should go see Ed. You know he’s going to be like he always was. Not taking care of himself. Working all the time. Forgetting to eat. Forgetting to sleep. If we didn’t go see him, we thought we might not ever see him again.” So the old friends went to visit their buddy in Stephensport. After the first trip, they continued to visit as often as possible. They helped their friend when they could, and they watched him fall apart.

“He made bird houses that looked like Frank Lloyd Wright designed them,” Alexander says. Further blurring the lines between fine art and folk art, he also carved beautiful, realistic duck and fish decoys, and built majestic weather vanes.

Even at his folksiest, Perry never stopped surprising his friends. “We were sitting around one night and it was dark,” Sykes recalled. “Ed says, ‘Y’all watch this.’ And before you knew it, there were laser beams running all around the house. He had mirrors set up here and there, and that light doesn’t degrade.”

After Perry’s death, Sykes took charge of Jake the parrot and as much of the artwork as he could, with a goal of getting it seen. A veterinarian said it was normal for older parrots to be cantankerous, adding that Jake would be fine once he was weaned off the alcohol. Getting the artwork in front of people proved to be trickier, but Mark and Becky Askew loved the work and agreed to show it in the Lakeland offices of A2H architects.

Miller says he initially had no interest in viewing the work. “I figured it would be the couple of good pieces on the invitation and maybe some unicorns,” he says. “But I went. And I’ve never seen anything like this in terms of a body of work. It was just amazing. So consistently good. So complex. So beautiful and so interesting. I immediately started bringing people out to see it.” Now, with the two MCA exhibits, he’s inviting the rest of Memphis to look.

One big question remains. What would Perry, who took such pains to stay out of the spotlight, think about his posthumous closeup? “Well, for starters, we’re not taking a commission,” Miller says, addressing one of Perry’s primary complaints.

Alexander takes things a little further: “If he was going to be anywhere in the world, Memphis or Spain or wherever. I think he’d want to be at the Art Academy. Back in Memphis, where it all got started.”