By now, the ever-growing fan frenzy for all things Big Star is a familiar riff in Memphis. Indeed, given that the band’s initial popularity was either overseas or among critics and collectors, the fact that they are actually popular in Memphis may be the final signpost in their march to immortality.

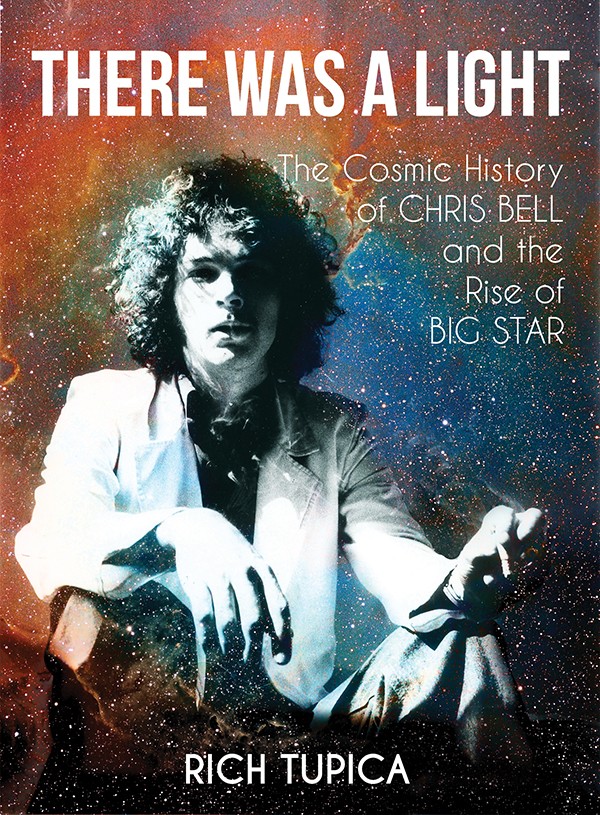

But the man who actually founded the band, having died in a car wreck in 1978, never had the time to retell his version of events. In the history of Big Star, the life of Chris Bell has long been a cipher of sorts. We heard tantalizing snippets of his story in the documentary, Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, but nothing as detailed as the reams of copy written on the diverse Alex Chilton catalogue. That’s changing, first with last year’s release of five LPs of pre- and post-Big Star material by Bell, and now with the publication of There Was a Light: The Cosmic History of Chris Bell and the Rise of Big Star by Rich Tupica.

A biography of an artist 40 years gone is a tall order. Tupica works around this by creating a Rashomon-like tapestry of quotes from those who knew him best. For those who are not already fans of Bell’s music, this can make for a challenging read, but it is a time-honored approach to the rock biography (cf. Please Kill Me by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain). As sheer storytelling, it only works if you have a stack of records beside you to whet your appetite. But you owe it to yourself anyway.

Tupica, a Michigan-based entertainment writer who’s contributed to Record Collector, Uncut, and American Songwriter, has done his homework — and his legwork. Though he writes very little as an author, except a few explanatory notes to create the context, his five years of labor on this volume yielded interviews and archival quotes from dozens of people, requiring four pages to list them all at the end. The final product is an encyclopedic compendium of sorts, illuminating Bell’s life from a thousand angles. One byproduct of this is the light shed on the interviewees themselves, many of whom, like John Fry, John Hampton, and Richard Rosebrough, are now gone as well. As such, the book serves as a worthy remembrance of these musical luminaries, too.

Once the reader begins to connect the dots, what can we learn of Bell’s life? He was clearly a scion of his restaurateur father’s hard-won wealth, with a family beach house in the Caribbean and a sports car, but in some ways this made his life more troubled than his peers’. Inner conflict shaped most of his brief life: a rebellious soul who still sought acceptance; a bit of an airhead (e.g., repeatedly losing vintage gear to thieves when left in his car) who was nonetheless a meticulous musician, engineer, and photographer; a driven visionary who’s very art conveyed (at times inaccurately) his own fragility.

As for the persistent speculation about Bell being gay, the book addresses the topic more straightforwardly than previous histories of the band, but fails to arrive at anything definitive. If Chilton and others claim that “I never knew anything about his gayness,” others might say, “We all knew it but didn’t go on about it.” Rosebrough details Bell’s emotional heart-to-heart on the subject, but the only romantic interests from his life mentioned are women. Yet the very ambiguity of the topic speaks to the repressed nature of Southern culture at the time.

One definitive point is that Big Star was very much Bell’s project. Chilton himself notes that “I just sort of did what the original concept of their band was … I just tried to get with Chris’ stylistic approach as well as I could.” It’s ironic, as the association of Chilton with Big Star is so fixed in our minds that even this volume devotes whole chapters to his post-Big Star career.

And, despite speculation that Bell’s car wreck was a suicide, Tupica’s research reveals how unlikely this is. Though he still lived with the disappointment of Big Star’s initial failure, Bell seems to have worked through his worst demons by 1978 and was looking forward to new musical projects. Reading of John Fry bolting out of bed at 1:30 a.m., when the accident happened, or Jody Stephens driving by the crash scene, not knowing it was his friend, lends an eeriness to Bell’s death, evoking the thin thread from which life and art hang suspended.