The good news: One way or another, the complicated tangle of the city/county school merger process may get untangled this year. Federal, state, and local officials are working on it, though they seem to be working in different directions. That’s all part of the tangle, which could become even more snarled than it already is. And that’s the bad news.

After regular business had finished at Monday’s public meeting of the Shelby County Commission, Chairman Mike Ritz made this add-on announcement concerning a status conference held earlier that morning between U.S. district judge Hardy Mays and attorneys in the still ongoing litigation relating to city/county school merger and the prospect of independent municipal school districts:

“I did visit with the attorneys in the courthouse this morning, and the circumstances were these: A new party to the lawsuit was asked to attend the meeting. The county school board was not a party to the lawsuit, but they were asked to be there.

“And what happened was that the judge said he was going to postpone his decision on the two remaining issues and asked for a special master to be appointed, with names to be submitted no later than Wednesday to overlook the activities of the school board, because he is not happy with the failure of the school board to appoint a superintendent, to take budget actions, and otherwise respond to the recommendations of the TPC [Transition Planning Commission] — which he feels in toto is a failure to conform according to his order of 2011.”

Ritz added, “There is nothing for us to do or not do. We don’t have to like it or not like it, but there we are.”

Earlier, Tom Cates and Allan Wade, attorneys for the suburban municipalities and the Memphis City Council, respectively, had, in separate meetings with reporters, said essentially the same thing and with the same matter-of-factness as would Ritz.

“We all knew” that the municipalities would be in the Unified District for at least a year, said Cates, in what may have been his frankest acknowledgment yet of that particular reality mandated by Mays in separate orders of 2011 and 2012. And that, both he and Wade said, was all that was discussed.

Mays’ announcement of his imminent intent to appoint a special master resolves a matter that has been hanging since his original order of 2011, which mentioned such an office, and its most obvious intent is to dispose of the remaining financial and organizational obstacles to school consolidation in the face of an approaching July 1st merger deadline.

But, while it is generally being treated as a de facto delay in ruling on remaining legal issues, pending whatever the Tennessee General Assembly does on school matters in the current session, it takes those issues, including the final provision of the 2011 Norris-Todd Act and the very feasibility of independent municipal schools, to the brink of final judgment.

Hence a largely rhetorical discussion in Monday’s commission meeting on a resolution by Wyatt Bunker, Terry Roland, and Chris Thomas, proponents of municipal schools, to remove the commission as a litigating party and, in effect, terminate the lawsuit.

Bunker rolled it all into a single ball, beginning with a conclusion he said he reached as a member of the old Shelby County Schools board a decade ago. “We knew back then that city schools were top-heavy. There’s a lot of waste, a lot of waste in that administration,” and bringing things to the present, which included last weekend’s retreat attended by commission members, Unified School Board members, and other county officials. A major point of concern at the retreat had been the board’s request for extra funding.

“We get to that retreat this weekend, they hand us a 145 million-dollar bill. … That made me quite angry, because it appeared to me that they were trying to avoid making the tough decisions that they need to make and instead just hand us a bill. … That’s why the municipalities don’t want to have anything to do with it. … That begs the question, Why are we tying them up in a lawsuit? They need to seat their board. They need to hire a superintendent. They need to obtain the capital improvements to support their school system, put in place everything that’s necessary. … Why don’t we get out of the way and let them get on about the business of educating children?

“And for those of you who believe this is a race issue? By definition, Shelby County Schools is more diverse than Memphis City Schools is. It’s not a race issue. It’s a very diverse school system. It’s a high-achieving school system. … You ought to vote with us, get out of the way, and let them make progress.”

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

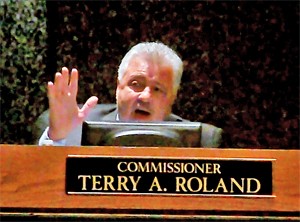

Roland: Nashville will act.

That was answered this way by Commissioner Walter Bailey:

“It takes two people to do a fox-trot. … If you don’t have an adversary, you don’t have a lawsuit. We’re asking them to concede the remaining issues, and the lawsuit will vanish. [We could] ask the court to enter the appropriate order. That would terminate the lawsuit. That would save hundreds of thousands of dollars. … That’s a quick remedy to end this lawsuit.”

And Commissioner Steve Mulroy segued from that into a reminder of the recently terminated mediation talks between the contending parties: “They’re saying it’s unreasonable to ask for a unilateral disarmament for their side. By the same token, it’s unreasonable to ask for a unilateral disarmament for our side. … The question is, Why won’t we talk and work out a settlement? … A mere three or four weeks ago, we were 90 percent of the way toward a complete local and comprehensive settlement.

“Abruptly, at the 11th hour, they walked away from the negotiations. And why? Because they had some sort of inkling that our Nashville overlords would meddle once again in our local affairs and give them everything they want.

“But,” Mulroy said, “there is a chance they won’t get every single thing they want out of Nashville. If we settle the lawsuit now, they won’t have to go to Nashville.”

The reported terms of what Mulroy referred to as an aborted agreement were essentially these: 10-year agreements between the suburbs and the commission permitting chartered school districts in six suburban municipalities; guarantees of racial diversity in the suburban schools; paid-lease agreements between the suburbs and the Unified School Board for existing school properties; and, in what seems to have been the sticking point, an agreement by the suburbs to equalize per-pupil spending with that of the unified system and to commit municipal sales tax revenues to that end.

In debate Monday, Roland responded, “Don’t say you ran away when you pushed [us] away.” He predicted that the General Assembly could make the local dispute moot by enacting legislation that would enable municipal schools and allow direct state funding of them, bypassing the county commission’s approval process.

Indeed, there are several measures tumbling around in Nashville at the moment, one or two that would legalize new municipal school districts, this time on a statewide basis, and others that would enlarge the state’s charter-school apparatus and create the kind of state control Roland spoke of. Last week, those measures drew opposition from representatives of the state’s Big Four school districts — Shelby, Davidson, Knox, and Hamilton counties — and reaction to them appears not to be predictably partisan.

Things remain to be seen up there, as, in fact, they do in Shelby County.

• Also on Monday: Inner-city Democratic commissioners Sidney Chism and Bailey joined with the suburban Republican bloc of Bunker, Roland, Thomas, Heidi Shafer, and Steve Basar to uphold the county’s existing residency requirements for Shelby County employees, a category that will now include those employees of Memphis City Schools, whose employer of record will be Shelby County after school merger becomes effective on July 1st.

The opposition of Chism and Bailey to an amendment that would have exempted the erstwhile MCS teachers was based on what Bailey referred to as a “freeloader” mentality on the part of people who work inside Shelby County but who pay their residence taxes elsewhere, a traditional inner-city view. Republican Shafer expressed similar views.

The ordinance, as passed, will give the affected teachers a five-year period to establish residence in Shelby County. However, the commission, by another bipartisan vote, this one going 9-4, passed a follow-up ordinance authorizing a 2014 ballot referendum abolishing the residency requirement for all county employees.