Wes Anderson’s got a shtick. And that’s okay.

Anderson’s been making movies for almost 30 years now, and he’s become one of those directors whose style is instantly recognizable. You can look at any random frame from Asteroid City or Moonrise Kingdom and instantly know who directed the film. People on TikTok who have never seen The Grand Budapest Hotel know Anderson as an aesthetic. His art direction is impeccable; his attention to detail is legendary; his camera movements are crisp and precise. He directs his actors to underplay and uses close-ups sparingly, which makes his films feel emotionally cold to some people. He also has a reputation for being “twee,” which might have been true when he made The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou but hasn’t been the case for years.

“Shtick” is a word that comes from the comedy world which means a character, bit, or routine associated with an individual performer. Maybe it’s a puppet, like Shari Lewis and Lamb Chop, or a catchphrase, like Rodney Dangerfield’s “No respect!” The truth is, every artist has got a shtick, if for no other reason than when you find something that makes people laugh, you want to keep doing it. For people like David Bowie and Lady Gaga who made a conscious decision to change everything about their acts every few years, the rejection of shtick becomes their shtick.

If shtick is inescapable, why not embrace it? Anderson certainly has. His filmmaking skills are sharp enough that he could do something else, but he chooses not to. And why should he? He does what he does better than anyone. Notably, other filmmakers who are influenced by Anderson adopt his precise attitude, but their films don’t look like his films.

Anderson has concentrated on more fully becoming himself, but that has led some critics to say that he is just doing the same thing over and over again. That could not be further from the truth. The films Anderson has made since his shtick fully developed have had very different themes. Moonrise Kingdom is about the invisible line between childhood and adulthood, and what it feels like when we encounter it. The Grand Budapest Hotel is both a character study and a story about the rise of fascism in Europe.

If there’s one film that can be accurately described as style over substance, it’s Anderson’s last film, Asteroid City. The ensemble cast that Anderson loves to assemble got the better of him, and the story-within-a-story-within-a-story structure was too clever and not very clear. It was beautiful to look at but not much else.

Anderson’s latest, The Phoenician Scheme, largely rectifies those problems. Yes, it has such an enormous ensemble cast that the poster looks a bit like a high school yearbook. But this time, the audience has a great focal point, in the person of Benicio del Toro.

They call Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda (del Toro) “Mr. Five Percent” after the cut he takes off the top on all the international business deals he makes. When we meet him, flying 5,000 feet above “the flatlands,” he is already fabulously rich — not the kind of rich you get by being an honest, above-board player. He is a stateless man who travels without a passport because, he says, “I don’t need human rights.” After a lifetime cutting deals with the most unsavory characters in the Middle East, he’s got one last plan that will set him and his family up for the next 150 years.

The details of the plan are not forthcoming and not really important. Suffice it to say it involves building a lot of infrastructure, like a giant train tunnel and a hydroelectric dam, in the Middle East. And it’s phenomenally expensive. Korda is flying to a meeting where he will ask someone else to foot the bill for the project when a bomb explodes in his private plane. This might not come as a surprise to someone who carries around a case of hand grenades to give as gifts (“I had some extras,” Korda says) but the explosion is caused by someone else’s bomb. It seems someone —in fact, several someones — has had enough of Korda’s schemes and wants to take him off the board permanently.

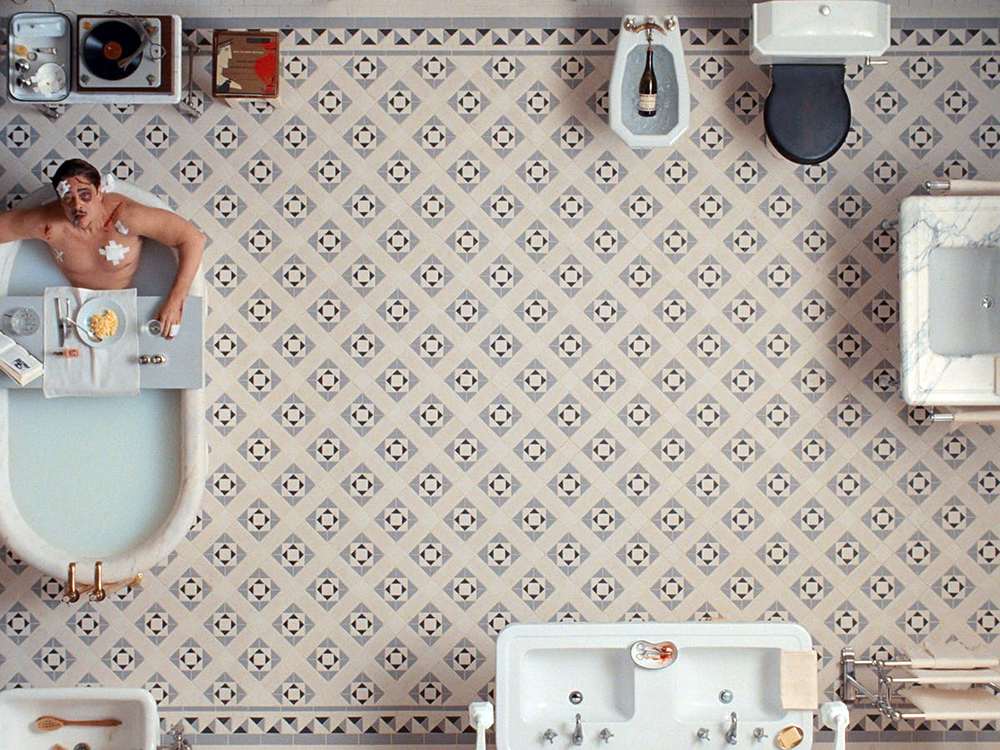

When the plane crashes, Korda has an out-of-body experience and visits the Pearly Gates, rendered in stark black and white. But God (Bill Murray) is not ready to judge Korda just yet and sends him back to Earth. Shaken by his latest brush with death (let’s just say this is not Korda’s first or last plane crash), he decides to secure his legacy. Instead of leaving his vast wealth to one of his eight sons (one of whom has a mischievous streak and a crossbow), he retrieves his only daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton) from the convent where he left her when her mother died.

Liesl is the only person in the film with a personality as big as Zsa-zsa, but she manifests it in a much different way. She is determined to become a nun, but she’s heard rumors for years that her father killed her mother, so she takes the opportunity to get to the bottom of the mystery. Along for the ride is Bjørn Lund (Michael Cera), a Norwegian entomologist turned tutor for the boys. The three of them crisscross the world looking for support for the scheme, meeting folks like Phoenicia’s Prince Farouk (Riz Ahmed) and American investors Leland (Tom Hanks) and Reagan (Bryan Cranston) for a hilarious game of basketball, gangster nightclub owner Marseille Bob (Mathieu Amalric), and second cousin and potential wife material Hilda Sussman (Scarlett Johansson). The final boss of the film is Uncle Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch sporting a truly epic beard), Korda’s estranged half brother who may actually be Liesl’s father.

Working with a new cinematographer, Bruno Delbonnel, Anderson creates some of the most intricate and gorgeous compositions of his career. With a fantastic look and a screenplay that keeps the action moving, The Phoenician Scheme is a return to form for one of the 21st century’s best directors.

The Phoenician Scheme

Now playing

Multiple locations