Last week, a tour bus idled next to Sam Phillips Recording Studio. Police vehicles stood by, lights flashing. Seeing Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland appear, a bystander might have thought a foreign dignitary was visiting. But no, this dignitary was all-American: Producer/director Ken Burns was in town to promote his new eight episode series, Country Music, due to premiere on WKNO and other PBS affiliates September 15th.

Not every Ken Burns premiere gets such a buildup, at least in Memphis, but the Bluff City figures heavily in his new project. By Burns’ own reckoning, 70 percent of the series’ 16 hours takes place in Tennessee. Indeed, the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development is one of the show’s major investors. Hence the tour bus. A whole entourage, including Burns’ co-producers, Dayton Duncan and Julie Dunfey, was in the midst of a four-city Tennessee blitz, bringing word of what was to come. It’s a tale that may surprise many by its diversity.

“Our first episode is called ‘The Rub,'” Burns explained over the barbecue luncheon. “And ‘the rub,’ with all due respect to the Rendezvous, is not about barbecue; it’s about the friction that takes place between black Americans and white Americans in the South. The banjo is an African instrument. The fiddle comes from Europe and the British Isles. And when they meet in America, the friction that’s given off produces many different offspring. One of them is country music. You can take the Mt. Rushmore of early country music greats, from A.P. Carter to Jimmie Rodgers to Bill Monroe to Hank Williams to Johnny Cash, and all of them have an African-American mentor who took their chops from here to there.”

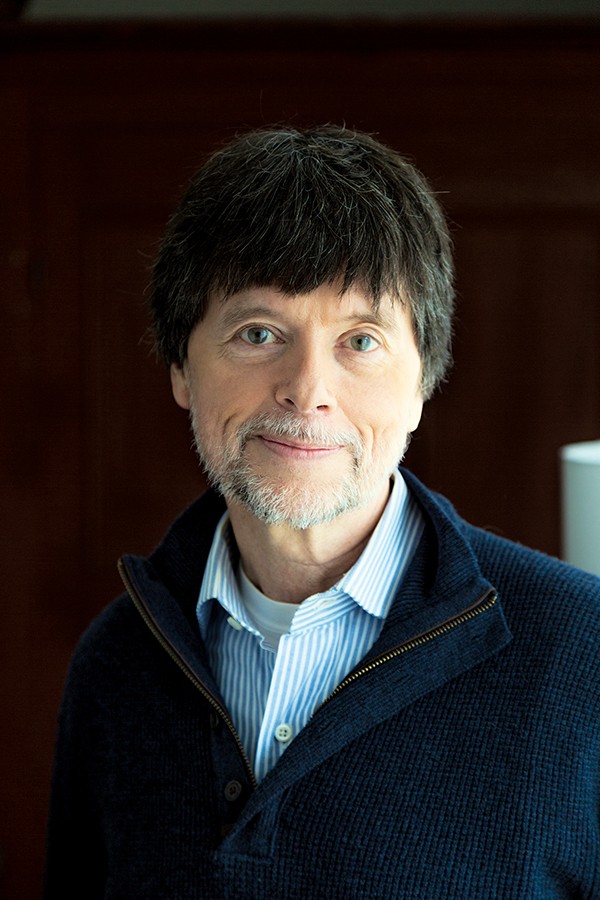

Ken Burns

Nowhere are the diverse underpinnings of country music more apparent than in Episode Four, which comprised the bulk of the preview segments shown in Memphis last week. As Duncan noted, “This thing we call country music came from a lot of diverse groups. Ballads, hymns, the blues, minstrel shows. It was always mixing and mingling. And this isn’t a film about rock-and-roll, but it makes the point that rock-and-roll has a connection to country. It’ll be a surprise to many that what Elvis was doing early on was going out and fronting for Hank Snow.”

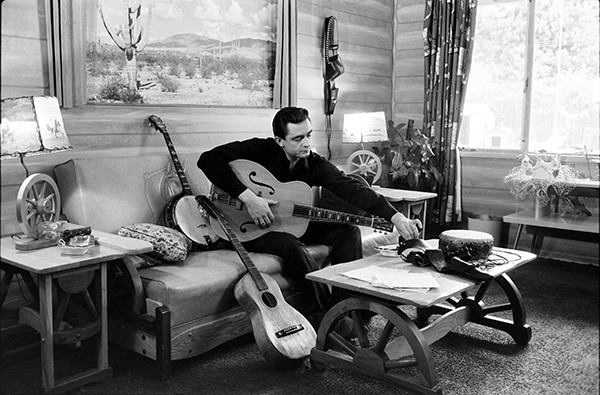

Even more revelatory were the segments on the early days of Johnny Cash, whose first years in Memphis spring vividly to life, thanks to newly discovered footage. “Archivists will dig deep for us. People will haul out the black plastic bag of photos from their attic and basement and let us go through them,” Dunfey said. “The Cash daughters just said, ‘We have all these family home movies.’ And actually they had never looked at a lot of it. They just handed little canisters to us.”

What the producers found was brilliant color footage of Johnny, first wife Vivian, and their daughters, picnicking in the Memphis area, not to mention films of Cash clowning with Elvis and Carl Perkins. Beyond the visuals, the episode highlights the impact on Cash of African-American jug band leader Gus Cannon.

With all the talk of diversity and “the rub” between cultures, I asked Burns what role anthropology plays in his work. “My father was a cultural anthropologist. He was telling you how people lived and interacted and what their language and their dress and their music said about who they are and how they interrelated with other people. My father was also an amateur still photographer. And my very first memory is being in the dark room he built in the basement of our tract house in Newark, Delaware, where he was the only anthropologist in the entire state of Delaware, and watching that magic alchemy, in that weird light and that horrible smell of those chemicals, holding me in one arm with his left hand, and with the right hand manipulating those tongs on a completely blank sheet of paper, in water, that suddenly appeared with an image. And so I can permit you, with the anthropology and the photography, to infer the rest.”

His final comments, too, revealed more than a little anthropology: “We are operating in this really unique space, that is between ‘us,’ that two-letter, lower-case plural pronoun, and the capitalized ‘U.S.’ And all the intimacy of us, and we and our, but also the complication and contradiction and controversy, as well as the majesty, of the U.S. We’re dealing with questions of freedom and race and gender, no more so than in this film.”