courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black

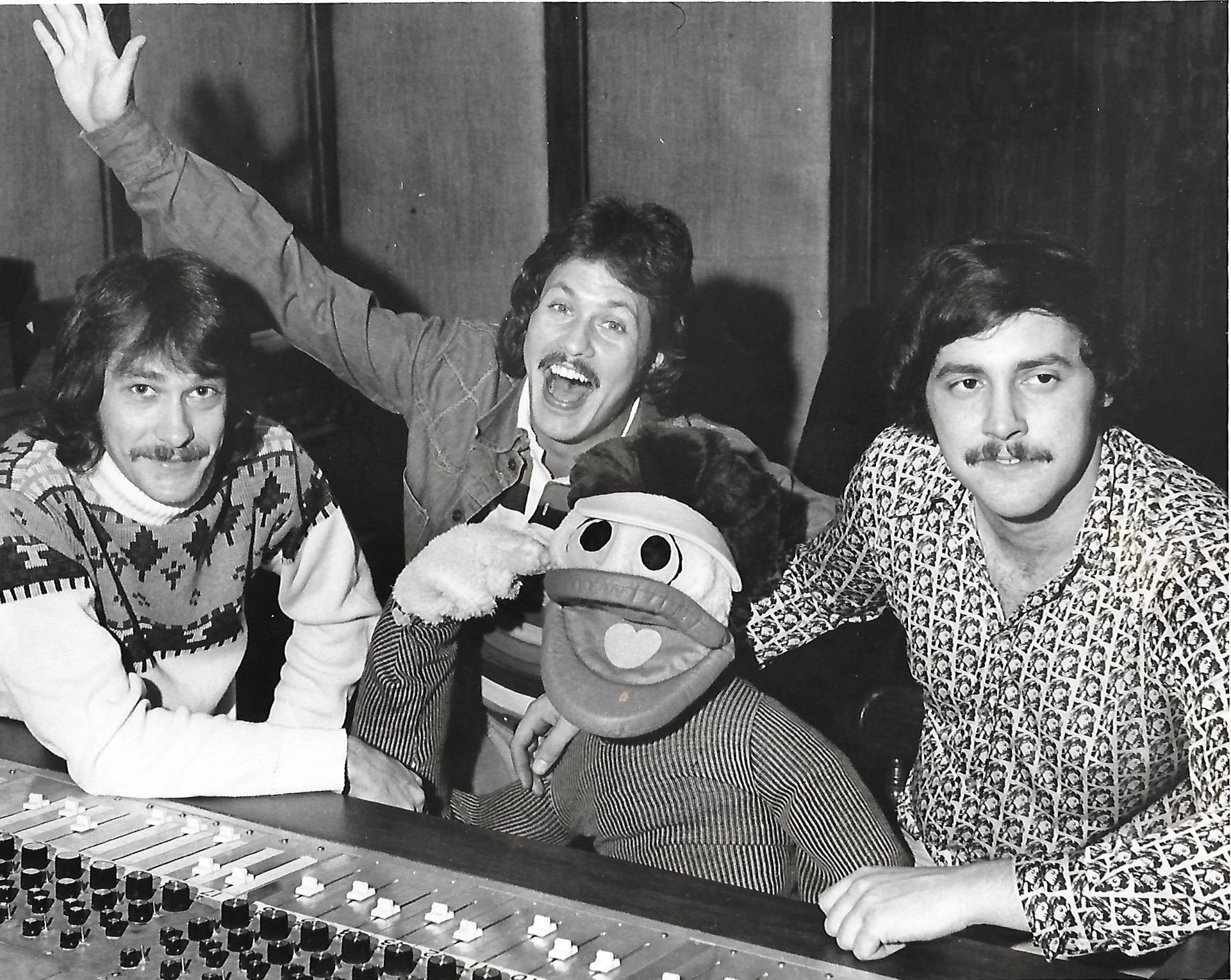

Bobby Manuel, Rick Dees, Wareen Wagner, and a Disco Duck.

Memphis is one of the greatest studio towns of all time. Sun, Phillips, Stax, American, and Ardent are just a few of the more well-known names, but a plethora of others helped capture the amazing music being made here over the years. One of them, Shoe Productions, was especially shy of the limelight in its heyday of the ’70s and ’80s, but cut some of the most memorable records of that era.

The studio was started by Wayne Crook and Warren Wagner in 1971, and Andy Black joined soon after. In 1977, Jim Stewart (the co-founder of Stax) and Bobby Manuel set up their Daily Planet Productions in the same building. Many decades later, Black went looking for whatever history of his old business might exist, and came up with nothing. So he and his son Nathan, already with years of experience in audio/visual production, set about making the documentary: Shoe: A Memphis Music Legacy. It screens Monday, October 26th, 6:30 p.m. at the Malco Summer Drive-In as part of the Indie Memphis Film Festival.

A quick chat with Andy and Nathan Black revealed that their documentary is just the tip of the iceberg. Shoe was buzzing with activity for over a decade, and the stories and recorded tracks are impressive.

Memphis Flyer: Memphis was really hopping as a recording city back in the ’70s.

Andy Black: Well it was. And I think part of that was, our undoing was because, we had the studio over there, and we were a bunch of kids trying to build things, and do everything ourselves with very little money. And Jim Stewart and Bobby Manuel came down. Stax had just folded and they needed to cut some stuff. And they were looking for a place to do it. So they cut there and loved the place. It was similar to Stax in the way it felt. They called their company the Daily Planet, right across the hall from Shoe. And we wound up building a second studio.

Jim used his connections with Atlantic and they bought part of the equipment. We got a brand new console, an MCI. And it worked out real well. On the Shoe side, we were doing everything ourselves. We built a console from the ground up. I mean, we etched the circuit boards and put every little component in every board in that console and soldered it together. There were about five or six of us working on it. It became such a unique sounding board, especially on the low end.

Then it got to where Jim and Bobby would come over to our studio and cut basic tracks, because they loved the way the bass and bass drum sounded. And we would go over to their side, ’cause that’s the side you wanna put the horns and the vocals on, ’cause it’s cleaner. So it became a back and forth thing. We were more or less rock and roll and pop, and when Jim and Bobby came in, a lot of people started coming over because of them, like Steve Cropper, or other people from Stax, or from Isaac Hayes’ band. So all the pop guys were going, “Wow, that’s really good. They’re good!” So we all learned from each other. Shoe was about the people and it became a learning place. We taught each other by bouncing ideas off each other.

And we kept a real low profile. Jim asked us to do that, because he didn’t want to deal with the media. Stax had just folded. He didn’t want to be bothered. And everyone thought he went “into hiding,” so to speak, and got out of the business, when really he was over there at our studio, and we were cutting every day. It turned into a real good working relationship. We kept it low-key. In this process, Nathan and I did “Take Me to the River,” and I had done a Stax documentary, just the audio. So Nathan shot everything.

courtesy Andy Black

courtesy Andy Black

The control room at Shoe Productions

I was over at Sun Studios, and killing time with the kid that was running it. And we got to talking about Shoe, and I told him all about it, and he said, ‘Man, I thought I knew everything about Memphis music back in the ’70s and ’80s, but I have not heard these stories.’ Well it turned out that that kid was [Grammy Award-winning producer and engineer] Matt Ross-Spang.

I went home and Googled “Shoe” and got nothing. It was just like we didn’t exist. I said, ‘Damn, we kept such a low profile, we’re getting left out of history.’ So I talked to Nathan and said, what do you think about us going in on this project together? Nathan was practically raised there. I used to take him to the studio with me all the time, as a young child. So he’s well aware of the story.

Nathan Black: It was interesting for me because one of the first things we did was get the old group back together. There’s a recording session in it. So that was the first time a lot of those guys had been there in 30 years, and going back into the space, and it was the first time I’d been in there in 30 years too. And the Daily Planet side is exactly the same way it was back then. It’s still a working studio, and everything’s the same, down to the carpet. It was like walking back in a time warp. I spent a lot of time there, but I was young, probably 8 or 10 years old. So I knew all the people, but I didn’t really know the stories. So it was interesting to me, hearing all those stories from people I knew and had been around all the time. I was just a kid going to work with my dad. I remember making little forts up under the grand piano, playing with my GI Joes.

AB: Jimmy Griffin was co-founder of Bread with David Gates. And he’s a Memphis boy. He was from Memphis and went out to L.A. and they formed Bread. And had many, many hits. And he came back and we became friends. He was out jogging one day, and came in and introduced himself. He and I and two other guys had a writing group. We wrote songs all the time. And we wound up cutting an album with Terry Sylvester of the Hollies.

Was that one of the first things you did there?

AB: It was an early thing. Actually, one of the first things we did was Jimmy himself, because Jimmy was such a good singer. And we had some writers, so we decided that Shoe needed to start a label, and we used Jimmy as our first artist on Shoe Records. It’s funny because the records have turned up a couple times on eBay, and they’re selling for between $50-$100 a piece — for a ’45! And I’m like, ‘Damn, I’ve got probably 75 of these things.’

There’s a whole section on “Disco Duck” and how that came to be. It was originally on Estelle Axton’s label, Fretone Records. [Celebrity DJ] Rick Dees had gone to her with the idea of doing a disco song. She connected him with Bobby Manuel and they finished it, and Bobby cut it, and RSO Records bought it. And they wanted an album right away. So we cut an album in two weeks. Every day, all day long.

NB: There is a whole section of the film about the Dog Police. I remember my dad taking me to the studio where they were shooting it. I even brought home some of the dog masks.

AB: They were doing jingles, because they were three of the finest jazz musicians in town. They’d go over the Media General and crank out those jingles like crazy. Shoe also did jingles, but so we could support our creativity in songs and records. So Tony [Thomas] and them came over and I wound up cutting two jazz albums with them, and both of them got shot down. They didn’t get a deal and they were so bummed out. So they said, We’re gonna do something REAL different. Whatever you want to do, Andy, it’s total freedom. And we didn’t have a lot of electronic gear back then, so I took a microphone and stuck it in the end of a vacuum cleaner hose and gave Tom Lonardo the other end and said ‘Here, sing into this.’

I remember when I was young and used to sing through the vacuum hose and it sounded so cool! So we did all kind of crazy things. And Wayne and Warren heard all this going on through the walls, and they became really interested in it. Wayne was getting into video at that time. MTV was starting to get pretty big. So it just married together. We actually did a whole album.

Still from ‘Dog Police’ video

NB: The video won MTV’s Basement Tapes, hosted by Weird Al Yankovic. I think it was NBC that picked it up and did an actual pilot, they were planning on making it a show. You can see it on YouTube. The pilot has Adam Sandler in it, and Jeremy Piven.

It seems like there was a cool experimental environment at Shoe. I noticed the Scruffs cut their debut there.

AB: Yeah! They used to come in and pull the night shift after everybody else had gone home to bed. The Scruffs would come in and cut til the wee hours of the morning. And then other people would show up in the morning and they would leave. We had two studios that were just pumping out projects all the time. I produced Joyce Cobb. We had a hit song with her, “Dig the Gold,” that went up to #42 in the nation on Billboard. And we had Rick Christian, who got a deal with Mercury records, and one of his songs got picked up by Kenny Rogers and he had a #1 hit with it. And we had Shirley Brown coming over there. We had Levon Helm coming over there. It became a very active place. And that’s why it puzzled me that no one knew anything about it. Then it dawned on me why.

That low profile.

AB: Yeah, it’ll get ya every time!

The first time I heard about Shoe was reading that Chris Bell cut some of “I Am the Cosmos” there. Were you in on that?

AB: I wasn’t in on that session. Warren did. They were friends, so Warren invited him and Ken Woodley to come down and Richard Rosebrough down to Shoe, and they came in late, ’cause that was the only time slot they could fit in there. They cut “I Am the Cosmos” and one or two others. And people are still interested in Big Star and Chris Bell. One day on Facebook, I saw where people were taking pictures through the windows and saying, “Look, I think this is the room where ‘I Am the Cosmos’ was cut.” And I looked at it and went, ‘No, that’s the bathroom!’

That track was actually cut on the other side of the building. We occupied both sides of this really great building. It was supposed to be a basement for a church. So the bottom floor was 16″-18″ of packed concrete and partly underground. So it was super quiet.

NB: Apparently the pastor of the church ran off with the money, so they only built the basement. That’s all that exists! You walk through the front door and you immediately have to go downstairs. So everything was underground. No ground floor, no windows.

AB: It’s really bizarre. We only had one little sign by the front door and that was it. It was just kinda word of mouth. Elvin Bishop came over. Dr. John. I could go on and on. We had to leave out a lot. In fact, there’s enough stories for us to do a Shoe 2!

The Story of Shoe Productions’ Many Hits, Brought to Life on Film