As producer Brian Eno once said, the Velvet Underground didn’t sell many records during their five-year run in the late 1960s, but everyone who bought one started a band.

They were abrasive, off-putting, and alienating — in other words, they were punk years before Lester Bangs coined the term to describe their descendants. One of the people who bought their records was a young English folk singer who performed under the name David Bowie. In 1971, he was playing the Velvets’ ode to methamphetamine “White Light/White Heat” to thousands of teenagers who were just there to hear Ziggy Stardust play “Space Oddity,” and continued to perform the song until his retirement in the early 2000s.

Despite their broad influence, the Velvet Underground is one of the last of the 1960s rock giants to get a career-spanning documentary. Now it seems that they were just waiting for the right person to come along to tell their story. They found that in experimental filmmaker Todd Haynes — an influential cult figure in his own right — whose infamous debut “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story” was told using Barbie dolls to stand in for his subjects. In I’m Not There, he rendered incidents from Bob Dylan’s life using five different actors to portray the singer, including Cate Blanchett.

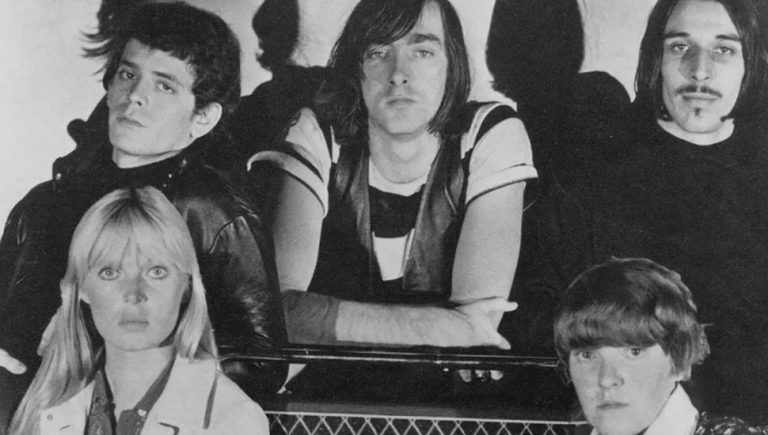

Despite the fact that they owed their careers to their discovery by Andy Warhol, very few people pointed cameras at Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, Mo Tucker, and Nico. This is a problem if you’re trying to make a movie about them. Hayes blows straight past the problem by embracing the experimental film scene bubbling up in Manhattan at the same time as the Velvets’ reign of terror. While assembling the documentary Woodstock, editor Thelma Schoonmaker discovered that a great way to spice up marginally useful footage is to employ split screen. If one image of, say, a drummer playing, is boring, but it’s the only in-focus thing you have to use, pair it with another boring image and suddenly it’s interesting. Hayes takes it to the next level—at one point, I counted 12 simultaneous images in one frame. (Hayes recently told an interviewer that he licensed 2 1/2 hours of footage for the two-hour movie. The film’s list of media credits was so long it gave me a panic attack.)

It all sounds disorienting, but the effect is evocative and clarifying. In the early going, you feel like you’re walking around the New York of the ’60s, looking everywhere for the strange art you heard about. By the time the Velvets hit the road with the Warhol’s revolutionary multimedia presentation, The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, you feel like you’re on their wavelength, and the San Francisco hippies they shocked and appalled seem hopelessly square. Here, Haynes shows his knack for picking the perfect anecdote, such as the fact that Warhol would grab random people from the crowd to run the lights, and just before the band took the stage at San Francisco’s Fillmore theater, promoter Bob Graham hissed “I hope you bomb.” (“Then why did he book us?” wonders a still incredulous Mo Tucker.)

To say this is a “warts and all” story is an understatement. Early in the film, Lou Reed’s sister mounts an angry, pre-emptive defense against people who single out the songwriter for his legendarily copious drug use. This is the guy who wrote “Heroin,” after all. Reed grew up in an oppressive household, and when his parents discovered he was bisexual, they sent him for electroshock therapy. But nearly everyone interviewed comments on how difficult he was to work with, or just be around. Warhol’s Factory is described as being a terrible place for women, but it doesn’t seem like the snake pit of backbiting and out-of-control egos was a great place for anyone.

But without the Factory, Reed and Cale would have never been paired with Nico, the stunning German actress who gave voice to “I’ll Be Your Mirror” and “Femme Fatale.” To Haynes, every bit of it, good and bad and weird, contributed to the volatile mix that produced music that spoke to the outcasts, the gender nonconformists, and the depressive nerds who heard something of themselves in “Black Angel Death Song.” With Summer of Soul, The Sparks Brothers, and now The Velvet Underground, 2021 is shaping up to be a banner year for music documentaries.

The Velvet Underground is playing at Malco Ridgeway Cinema Grill.