In the premiere of the six-episode miniseries reboot of The X-Files, agent Fox Mulder (David Duchovny) meets Tad O’Malley (Joel McHale), a right-wing talk show host in the mold of Glenn Beck. As he is about to get into O’Malley’s limo, Mulder snidely remarks that paranoia has made the younger man rich. Back in the 1990s, conspiracy was a cottage industry Mulder ran out of the basement of the FBI’s Washington office. In 2016, it’s the founding sentiment of the Tea Party, and thus big business.

Organized political paranoia is not new to 2016, nor was it new to 1993, when Special Agent Dana Scully (Gillian Anderson) was assigned to keep tabs on Fox “Spooky” Mulder’s paranormal investigations. In his 1964 essay for Harper’s Magazine, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” historian Richard Hofstadter traced conspiratorial thinking back to the 1797 publication of a book called Proofs of a Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Government of Europe Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Freemasons, Illuminati, and Reading Societies.

Hofstadter’s focus was on the right-wing, anti-communist paranoia that had birthed the House Un-American Activities Committee and the John Birch Society, whose crackpot beliefs about water fluoridation were immortalized by Sterling Hayden’s General Jack Ripper character in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. But in 1964, there was another strain of the paranoia virus spreading to the left. The Warren Report on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was released less than a month before “The Paranoid Style,” and people were already finding holes in its conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone. As the 1960s rolled on, with more assassinations, riots, war in Vietnam, and general social chaos, the radicalized left began to take what Hofstadter called “the characteristic paranoid leap into fantasy.”

The American cinema of paranoia began in 1962 with The Manchurian Candidate, where Frank Sinatra and Janet Leigh uncover a Communist brainwashing plot. The spy genre jumped onboard the paranoia train in 1965 with The Ipcress File, whose dark vision contrasted with the swinging Bond films. In the 1970s, Warren Beatty starred in The Parallax View, Robert Redford went undercover in Three Days of the Condor, and Dustin Hoffman was tortured by secret Nazi Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man.

The 1970s were also the heyday of the paranormal, with public interest spiking for UFOs, cryptozoology, and the Bermuda Triangle. Spielberg drew on this rich vein of weirdness for his 1977 masterpiece Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which defined the visual style of The X-Files.

The apex of the conspiracy genre came in 1991 with Oliver Stone’s epic JFK, which earned its Best Editing Academy Award in a breathless sequence where Donald Sutherland lays out the details of the conspiracy to kill the president to Kevin Costner. The same year, Duchovny portrayed an FBI agent on David Lynch’s Twin Peaks.

Chris Carter successfully synthesized those threads into The X-Files, whose nine-year run peaked in 1997 with almost 20 million weekly viewers. He pioneered the contemporary television formula of long-form storytelling sprinkled with stand-alone, “monster of the week” episodes. So in this age of retreads, it seems like a natural choice for a revival.

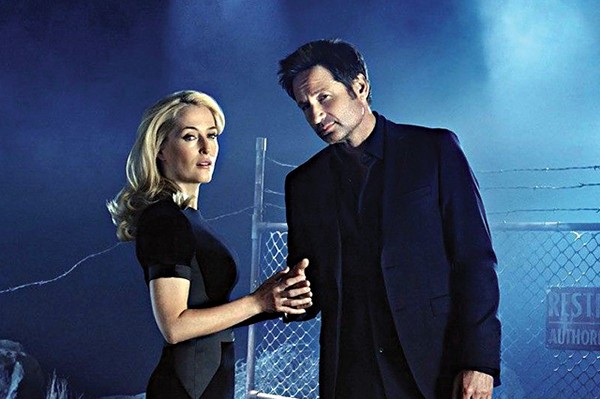

But the premiere of the six-episode miniseries reveals that the 1990s conspiracy formula doesn’t adapt well to the post-9/11 world. Duchovny remains his charming, if slightly wooden, self, and Anderson’s take on Scully is more confident and subtle. The leads’ onscreen chemistry is stronger than ever, but since Mulder and Scully have actually had a (possibly alien hybrid) baby together in the show’s later seasons, the Sam-and-Diane, will-they-or-won’t-they tension is missing from their relationship. Carter’s writing, on the other hand, is a lifeless attempt to graft 1990s paranoia onto today’s more hard-edged, legitimately scary right-wing worldview. The premiere’s attempt at emulating JFK‘s immortal Mr. X sequence falls flat. Even worse, Carter’s instincts for suspense seem to have failed him. It was years before Mulder saw a real UFO in the show’s original run, but he touches one in the first 30 minutes of the reboot.

Still, all the pieces are in place, and the miniseries’ third episode, “Mulder and Scully Meet the Were-Monster,” written and directed by Glen Morgan, whose “José Chung’s From Outer Space” is the best episode of the original series, looks promising. But after the lackluster premiere, the miniseries may only be satisfying to those who want to believe.