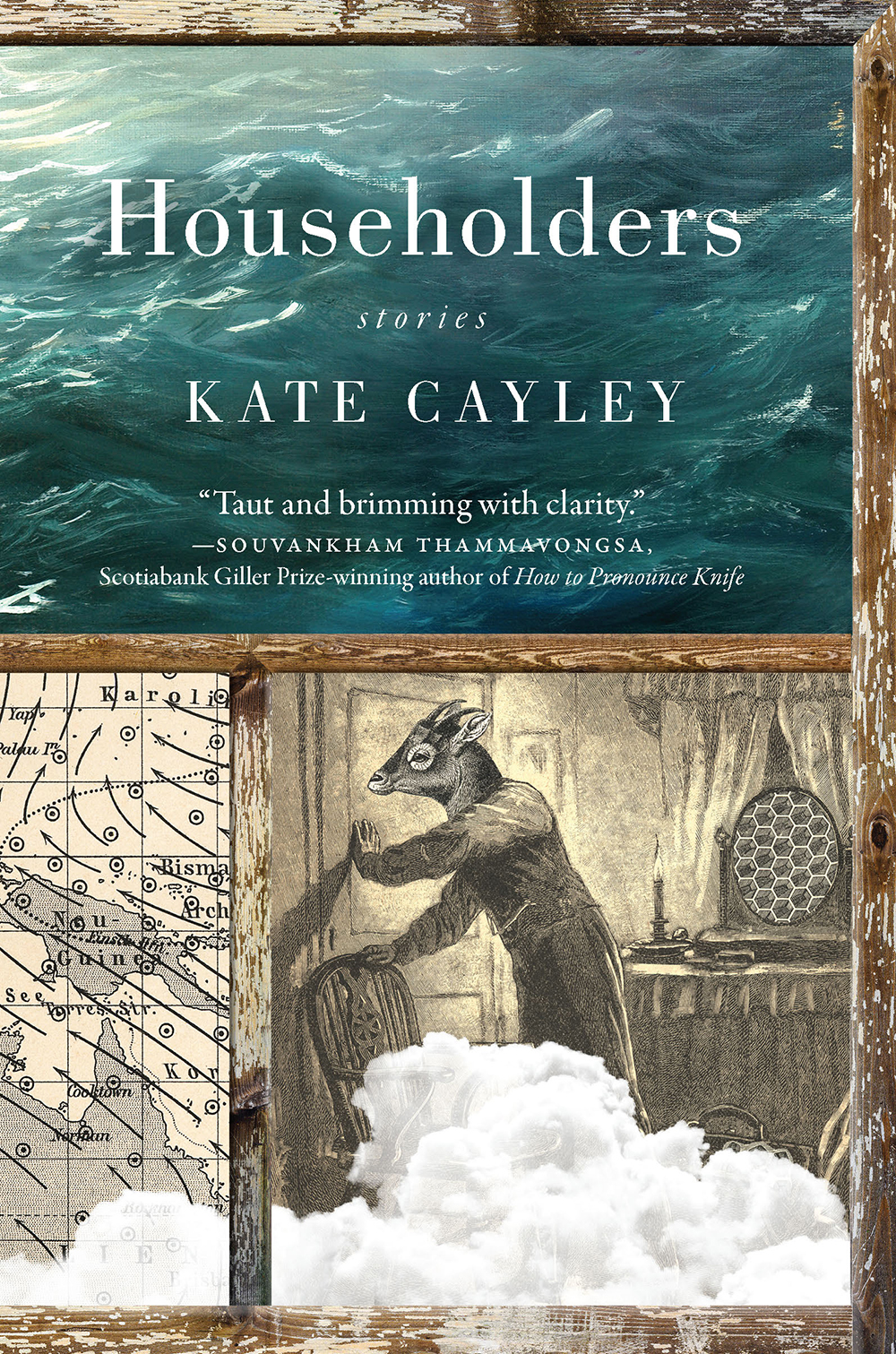

At a time when once-in-a-lifetime climate catastrophes are more and more commonplace, where each election is framed as a battle for the nation’s soul, it’s understandable that salvation is an idea with no little allure. So it’s no surprise that Kate Cayley’s Householders (Biblioasis), which the acknowledgments point out the author edited in March 2020, is a short story collection much preoccupied with salvation.

In Cayley’s collection of haunting short stories, mothers attempt to save daughters from the evils of contemporary living, and then from scarcity and hunger; daughters attempt to save mothers from lonely deaths in antiseptic nursing homes; and there is even a woman who disguises herself as a nun.

The stories in Householders form an interconnected narrative. Some tell parts of a larger story through a lens that spans decades and different perspectives, while others are connected only tangentially.

The first story in the collection, “The Crooked Man,” is one of the latter. It tells of a gentrifying neighborhood and stands as a warning against assumptions. With a struggling family working to make ends meet and to make a place for themselves, there’s a whiff of Sarah Langan’s fabulous Good Neighbors in some of the plot turns and settings, but Cayley makes the story all her own.

Her characters are often portrayed at extremes — living on a religious commune, engrossed in the self-contained world of academia, surviving on welfare and at the edge of town in a trailer slowly being reclaimed by the hills. Sometimes they live two lives, like the protagonist of “Pilgrims,” one of the most immediately compelling stories in the collection, in which the unnamed protagonist poses as a nun for an online blog. Her life can be divided into sections, a clearly demarcated before and after, and then there is the saintly life of Sister Bernadette, distinct from the protagonist’s actual identity.

“She wanted to be offered a pure sympathy,” Cayley writes in “Pilgrims.” “Now she wanted people, but no one she actually knew, because they knew her as herself—shy, not always truthful, envious of whatever she was not, stupid about men.”

If salvation and forgiveness are motifs of Householders, so, too, are past lives and former identities. Often, Cayley’s characters, flawed but sympathetic, feel they must jettison versions of themselves to be saved, whether spiritually or in a more tangible, mundane way. Several of the stories follow Naomi (formerly known as Nancy) and her daughter Trout. The two are inhabitants and, later, refugees from the religious commune known as the Other Kingdom. Both worlds offer something the other lacks. Naomi doesn’t miss the mindless consumption of contemporary society while living in the Other Kingdom, but she worries that they may never do better than subsist there. Back in the city, she misses the closeness of the commune, the feeling of family, but she can at least eat a full meal.

Eventually, the Covid pandemic makes its way onto the pages of Householders, often mentioned in passing, almost on the margins. At the Other Kingdom, Saul believes the pandemic is a sign of the end times, but Trout thinks that little in life is so obviously divided into phases — the beginning, the end. “Outside, away from their rarefied stale air, she’d come to feel that everything was not so decisive. That everything that pulled one way also pulled in another.”

In Householders, people leave often, but some people stay. Forgiveness is much sought after but rarely given freely, so Cayley writes with a passion that seems to extend that longed-for forgiveness to her characters when they cannot bring themselves to do it for themselves. People are pulled one way, but also in another, and, as in life, find themselves somewhere between extremes.