Over the course of my lifetime, three sports-related stories have staggered me. I say sports-related because these were stories that unfolded on a scale that dwarfed the athletic endeavors of their central character. The first occurred 20 years ago this month, when basketball icon Magic Johnson announced that he’d been diagnosed with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. The second staggering tale from the greater sports universe came in June 1994 (just a few days after my wedding), when football icon O.J. Simpson was followed along an L.A. freeway by a helicopter in the aftermath of his wife’s savage murder.

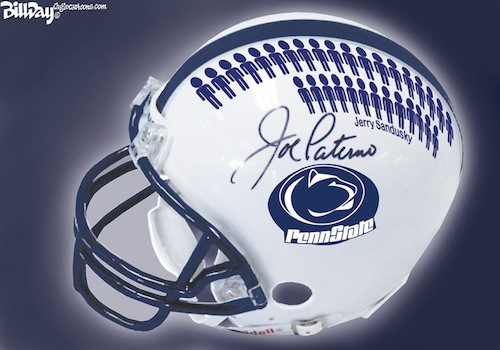

Bill Day cartoon

Bill Day cartoon

And now there’s the Sandusky Affair. Former Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky is charged with 40 counts of sexual abuse involving boys, charges that cover a 15-year period (1994-2009) in which higher ups — most notably iconic Nittany Lion football coach Joe Paterno — apparently looked the other way as a monster stalked his prey. This story should stagger us for years to come. (As my colleague Jackson Baker points out, we must allow the legal system to do its thing. But there’s a lot of smoke with 40 charges.)

As heartbreaking and tragic as Magic’s announcement felt in 1991, we knew the athlete himself was the primary victim of his own decisions and behavior. As horrific as the murders of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Goldman were, there were “only” two victims. Now with the truth emerging about Sandusky and his predatory ways, the victims under this latest headline could be counted in the dozens, if not hundreds. (When a grand jury report mentions eight victims, you can rest assured the number is a fraction of the total.)

With due respect to the athletic achievements of Magic and O.J., they are not in the category of Joe Paterno. In digesting Paterno’s firing last Wednesday after 46 years as the head coach at Penn State, I could come up with only two other college coaches (both basketball) I consider of similar renown when we measure their achievements in the arena and in the larger, more important, picture we know as life: UCLA’s John Wooden and North Carolina’s Dean Smith. Forget Paterno’s 409 wins and two national championships. This is a man whose program graduated as many as 89 percent of its players. (In baseball terms, this is a big-league player hitting .450.) A Penn State library was built with funds raised entirely by Paterno and his wife. Joe Paterno is, by most every measure, a decent man. An exceptional man, even.

But Joe Paterno had at least one blind spot, at least one breakdown in judgment. Who knows when Paterno first got wind that his longtime assistant may have been acting inappropriately with children? Perhaps it was 1999, when Sandusky retired at the still-young coaching age of 55. Perhaps it was in 2002 when, according to the grand jury, a graduate-assistant approached him having seen Sandusky raping a child inside Penn State’s football facility. Whenever Paterno became aware, he should have called the police. Had that call been made, we wouldn’t have a story of such magnitude today (and the Sandusky victim count would be much smaller).

With the demise of a man who belonged on a college sports Mount Rushmore, I see three lessons we should carry into a future made less certain by the reminder that there are, indeed, monsters among us:

• There are authority figures … and there’s the police. The grad student who witnessed a crime (on a horrific scale) reported what he’d seen to a man (Paterno) he considered an authority. Paterno then reported what he’d heard to another authority (a Penn State vice president). And so the word traveled and, presumably, was minimized with each telling. Forget good-Samaritan laws that obligate us to report crimes we witness. Let’s remember the moral obligation we have, particularly to victimized children. Predators rely on silence and fear … and a blind eye from authority.

• Exclusive power is dangerous. Paterno achieved a status in and around Penn State that, frankly, isn’t natural. It’s the stuff we read and hear about when tyrants are taken down overseas. (To be sure, Paterno’s elevated stature was gained through benevolent actions.) In the words of Theodore Roosevelt, “The rule of the boss is the negation of democracy.” When looking back on Paterno’s fall, we’ll see that the rule of the boss was, in this case, the negation of justice. However much power a person is seen to hold, there must be someone brave enough to tell him (or her) when a decision is wrong. “Coach, you really need to go to the police with this.”

• Sports are a privilege, and supplementary. Penn State did the right thing in firing both Paterno and president Graham Spanier. The student rally in support of Paterno last Wednesday night was unsettling. (As was the football game played Saturday. Should have been cancelled.) We too often describe our favorite athletes and coaches as heroes. They’re not. The young men who came forward to finally bring Jerry Sandusky to justice … they are heroes.