Put on your hip waders kids, I’m gonna pontificate a little.

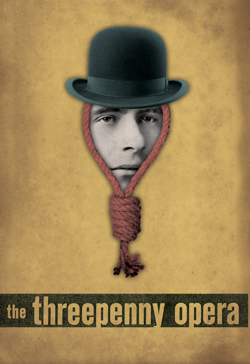

Shortcomings (and there are many) aside, anybody interested in the work of Bertolt Brecht will want to see the Mark Allan Davis-directed production of Threepenny Opera at the U of M. The student actors are top notch, the material is meaty, and the band takes an admirably squawking stab at Kurt Weill’s lurid, lurching score. More to the point, it’s been 24-years since Memphians last had a chance to see this landmark musical, that vintage production was shut down after only two preview performances, and post-millennial Memphis may never see an Arturo Ui or Mother Courage.

That said, pack a sack lunch and get ready for a long evening of underwhelming design, cutsie anachronism, and

self-indulgence.

Brecht’s the reigning king of misunderstood artists. Threepenny Opera, his most accessible work, is a regular victim of these misunderstandings.

Too often the word “Brechtian” is flung around as a synonym for “unnatural,” or, “weird,” or “confrontational,” or it’s used to describe performances that are heavily politicized or formalized to an extreme. I’d make the unlikely case that when Brecht denounced naturalism as the Theatre’s most ridiculous convention he became the Theatre’s best naturalist.

For what it’s worth I don’t think Brecht’s American heirs are writing Broadway musicals They’re in bands, or burlesque shows, or they’re in Chicago doing improv, or they’re touring the country with the WWE, an organization that no longer pretends wrestling is a real sport.

Nobody mistakes realistic sets for busy city streets or believes somebody died in the big fight. So why lie to an audience that knows better, especially when an empty stage is everywhere and every actor, freed from the pretense that he or she is anything but an actor, contains the universe?

Brecht came of age as a playwright in the mid-1920’s, alongside artists of the Bauhaus school. It was a time when edgier creatives found beauty in function in a way that prefigures the contemporary industrial design of Steve Jobs’ iProduct. Designers working on a piece like Threepenny Opera aren’t expected to craft literal spaces for artificial humans to talk to themselves, pretend not to see the audience, and yell at each other when they really should be whispering. They are tasked with building spaces well suited for storytellers, puppeteers, dancers, musicians and other human vessels for the didactic Playwright’s comical lectures and crass object lessons.

Everything that’s brought onto the Brechtian stage acts. Costumes, when appropriate, become uniforms that turn whores into “whores” and brides into “brides,” and brides into whores, and so on, eliminating the need for too much in the way of an introduction.

The most Brechtian moment in the U of M’s Threepenny happens before the show starts, and takes the form of an extended teaching skit showing the audience what happens to inconsiderate ticketholders who forget to silence their phones. It’s a funny bit of the ultraviolence, but it does go on. It’s followed by a second false start in the form of an extended curtain speech where one person greets the audience in badly-read German, while a second interprets. Big comedy. Eventually, the actors are permitted to start the play, which begins in medias res, forgoing the “Ballad of Mack the Knife,” a number that opens and closes the show in every version of the script I’ve ever encountered.

With its off-stage fog machines and finger-popping homages to Bob Fosse this Threepenny tries like a champ to have its Brecht and Broadway too. These have always been strange bedfellows, and the progeny is always malformed.

Ken Ellis’s scenic design is blah and artificially shabby. With notible exceptions, Melissa Penskava Kosa’s costumes never say much about period, place, class or character. In clothing and choreography one is more likely to see a Fosse chorus than a Brecht ensemble which, to take nothing away from Fosse, is like expecting a glass of wine but getting a wino instead. Or, maybe it’s the other way around.

The singing is all strong and the slapstick is mostly funny but points are missed and the pace crawls. For all of Brecht’s mystique, this frank story about Macheath, a dangerous, dashing pimp and highwayman who marries the teenage daughter of Mr. Peachum, a “legitimate” businessman operating an exploitive temp service for beggars, isn’t far removed from any other comedy of manners. Physical humor is encouraged, but the real comedy is rooted in brutish thugs behaving like proper gentlemen while upright Bible-quoting citizens operate like whores and extortionists. When these distinctions aren’t lost in badly mixed sound they dissipate into the numbing blandness of a show with lots of slick tricks and no stylistic continuity.

I didn’t see a translator’s name listed in the program and couldn’t find any history supporting Davis’ choice to eliminate the Balladeer, give his song to Mackie’s old flame Jenny Diver the whore, and move it from the beginning to the middle of the show. It’s a decision that serves Threepenny no better than a series of tacked on transitional skits that, while clever, add at least 20-minutes to the evening. Brecht/Weill songs don’t advance the action like American musical numbers do, and pairing the slow-moving “Ballad of Mack the Knife” with the equally slow-moving (but beautifully sung) “Solomon Song” stops the show in its tracks, and not in a good “show stopping” way.

The U of M’s Threepenny Opera is abundantly creative when it comes to inventing original bits that are only loosely connected to the script, but far less so in finding the vibrant, violent, and hungry spirit of a vibrant, violent, and hungry piece of theater.

Hats off to Jacob Wingfield (Macheath), AJ Bernard (Peachum), Janie Crick (Mrs. Peachum), Kristina Hanford (Polly Peachum), Shakiera Adams (Jenny Diver), Elizabeth Kellicut (Lucy Brown), and Sean Carter (Tiger Brown) and to a talented chorus who collectively make a tough night of theater worth the effort.