Film, like all art, has its own cycles. It’s not just cycles of marketplace expansion and contraction, or the rise and fall of great stars — although those are things that affect film production — but of artistic direction and audience taste.

In the 1990s, the so-called indie era began with a flowering of filmic weirdness. There was no shortage of social realism, like Kevin Smith’s Clerks, a no-budget look at the world of the service economy’s working stiffs. But there was also formal experimentation, like Quentin Tarantino’s timeline-scrambling structures; magical realism, like Spike Lee’s nods to musical theater; and downright surrealism, like Stephen Soderbergh’s experimental cul-de-sac Schizopolis. By the 2010s, the cycle had receded. Mainstream studio films had been taken over by magic and superheroes, so the underground reacted by swerving toward realism.

Now, there are signs that the film weirdos want to get weird again. This January, the Sundance lineup was crowded with magic, such as Kentucker Audley and Albert Birney’s Strawberry Mansion and Dash Shaw’s animated tour de force Cryptozoo. Then in July, the Cannes Film Festival awarded the Palme d’Or to Titane. Director Julia Ducournau became only the second woman in history to win the festival world’s most prestigious award — and, since Jane Campion’s The Piano tied with Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine in 1993, the first to win it outright.

If you’ve heard anything about Titane, it’s probably that this is the movie where a woman has sex with a car. I’m here to report that yes, that absolutely does happen more than once, but there’s a lot more to it than that. We first meet Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) when she is a bratty tween. Angered by some unseen slight, she’s annoying her father (Bertrand Bonello) from the back seat as he drives on a French freeway. But the family conflict takes a tragic turn when Dad, chastising his daughter, takes his eyes off the road and crashes the car. He’s okay, but Alexia sustains a fractured cranium, which requires the implantation of a titanium plate to fix. She survives the injury, but the doctor warns Alexia’s parents to “watch for neurological signs.”

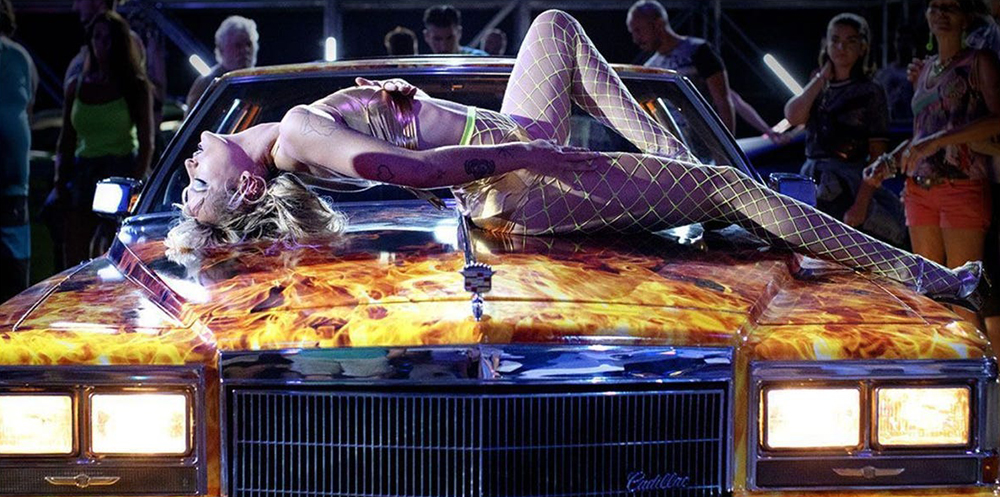

When we flash forward a decade or so, there is no shortage of “neurological signs” with Alexia. You would think her youthful brush with death would have put her off cars, but in fact the opposite has happened. Alexia loves cars — I mean, she really loves them. She makes her living as a booth girl at automotive shows, getting paid to dance seductively with custom autos. When random guys follow her into the parking lot to hit on her, she simply kills them. See, she’s not just a sexy technophile, she’s also a dangerous psychopath who has been terrorizing Europe for years.

After gruesomely dispatching a would-be rapist with a chopstick, Alexia works off a little extra energy with a Cadillac lowrider that’s been giving her the come-hither headlight. A few recreational slayings later, she finds out that 1) the cops are onto her, and 2) she’s pregnant with the Caddy’s car-child. She goes on the lam, but a close call with the gendarmerie causes her to decide that she needs to radically change her appearance. After an excruciating sequence where she remakes her face with brute force, she poses as Adrien, a missing child whom she may have murdered. Adrien’s father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), is a fire captain who has been mourning his disappeared son for a decade. He accepts Alexia as Adrien because he wants it to be true. But Alexia’s Adrien gambit is destined to be short lived, as she grows more and more visibly pregnant. If you think it’s going to be awkward to explain to Vincent that she’s not who he thinks she is, throw in the fact that his “son” is also pregnant with a car baby.

I’m a big fan of Ducournau’s film Raw, which transforms eating disorders into cannibalistic urges for some cutting body horror. Titane is a lot messier and more uneven. It starts off strong, with Rousselle’s fearless performance channelling Malcolm McDowell’s charming psychopathy from A Clockwork Orange. But once she takes up with Vincent, and Ducournau ramps up the paranoid body dysphoria, the story loses momentum. Even if the director can’t quite stick the landing, Titane is a visually ravishing and thematically daring film unlike anything else you’ll see today.