Shaking in the cold with his mother, Alex Ortiz, 10, stood in his underwear at the Mexico border — his father’s alcoholism and death threats behind them in Honduras, the United States in front of their eyes.

He gripped her hand as they crossed the river into Eagle’s Pass, Texas, where they were granted a six-month stay at a U.S. Border Patrol Station. Soon they’d be reconnected with family in Memphis, and, soon, they would overstay their visas.

“I remember driving over the bridge into Memphis from Arkansas and seeing the skyline,” Ortiz, now 24, says. “I had never seen anything like it. Coming here as a young kid, it was all an adventure to me. I just saw it as an experience to explore a new place.”

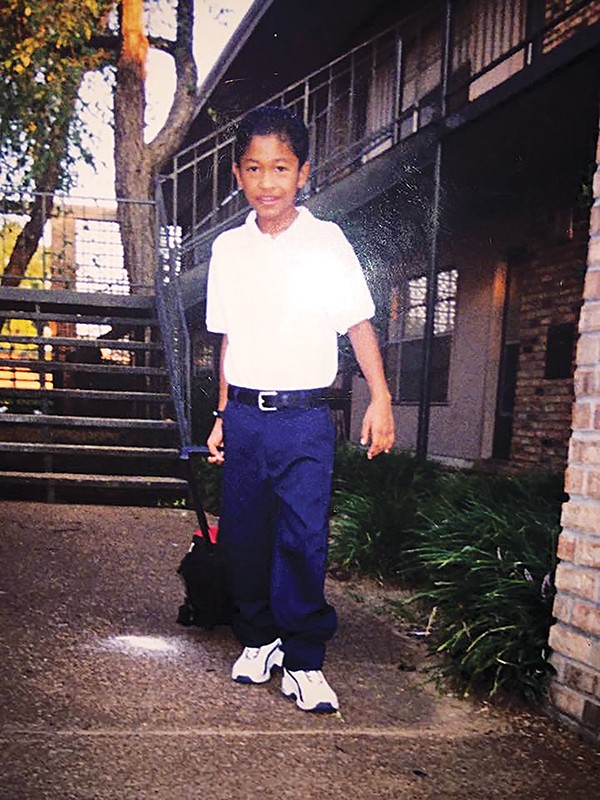

Alex Ortiz, now 24, emmigrated to Memphis when he was 10 years old.

It was 2003 when Ortiz and his mother arrived in the United States, nine years prior to President Barack Obama’s executive order that founded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration program. The initiative protects from deportation those who emigrated to the U.S. before the age of 16, and grants them work authorization and a social security number. About 13,000 immigrants have qualified for DACA in Tennessee, said Lisa Nikolaus, the policy manager with the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition.

With the same executive authority that created the initiative, President-elect Donald Trump could, and likely will, sign it away. Trump said last week immigration would be a top priority and said Sunday he’ll immediately deport 2 million-3 million undocumented immigrants. He’s standing firm on rhetoric that fueled his campaign: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … they’re rapists.” Overturning DACA would have devastating consequences, Nikolaus said.

“It would have a ripple effect not just for these people and their families, but to the businesses that employ them, to our local economy,” Nikolaus says. “It would drive them underground and be a huge devastation for our state.”

Ortiz, who grew from a fifth-grader who couldn’t speak English to the valedictorian of his high school class, was a sophomore in college on a full scholarship when he qualified for DACA. The program granted Ortiz opportunities like interning with Congressman Bennie G. Thompson, a member of the Committee on Homeland Security.

“DACA took me from having a lot of insecurity about what I was going to do with my life to having some ground to stand on,” Ortiz says.

Mauricio Calvo, executive director of Latino Memphis, said he doesn’t think the president-elect will be able to implement many of his complex and expensive campaign promises. He fears, though, Trump will make immigrants the scapegoat for the country’s economic challenges. Calvo hopes the Trump administration will instead create strategic comprehensive immigration reform through bipartisan efforts.

“Latinos are, and will remain, an important part of our local economy,” Calvo said. “In many ways, we are literally and figuratively helping to build our amazing city, the place that we all now call home.”