Valerie Piraino will be giving a talk at Crosstown Arts tonight (Wednesday, Nov. 20), 6 p.m.. The emerging artist, who lives and works in New York, was previously a resident artist at The Studio Museum in Harlem, and has shown work at Queen’s Sculpture Center and Chicago’s Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. Her Crosstown show, “Reconstruction” combines recent works with earlier installations.

Piraino works largely with transfer process, a method that she says is “very much embedded with photography.” Most recently she has been working with fabric transfers, though her Crosstown show contains earlier iterations of this interest: slide projection, printmaking, even embossed wax seals.

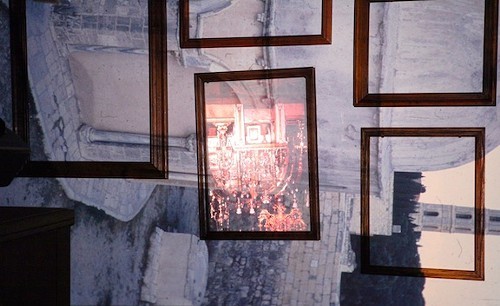

The show consists of five correlated installations: an array of small, handmade prints depicting old furniture; a row of vignette-shaped, framed mirrors; 11 wooden frames that contain projected slide images from several decades ago; and another slide image, projected into a corner at slightly below waist-height. The gallery space is bisected by a makeshift wall, giving the room a sense of front and back.

The idea of a transfer operates in “Reconstruction” in a couple different senses. There is the obvious transfer of one material to another, but there is also the thematic transfer of memory, both personal and historical. Piraino’s work attempts to reconstruct personal and family history but pays material reference to Victorian-era (read: American Reconstruction-era) furniture.

Piraino began this work when she inherited a large collection of family slides. She says, “Much of the context [of the photographs] has been lost as family members passed away. All of that has since been folded into the work and has really become a central question for me… how to you reconcile having personal objects with very little context?”

History, in Piraino’s work, is repressed, evidenced only by its inexplicable leftover objects. Her row of vignette-shaped mirrors are marked with a centered, creme-colored wax seal. They cast ovals of light onto the gallery floor. There’s a domestic simplicity and beauty to the mirrors, but the work is frustrating. It doesn’t tell a viewer what she or he wants to know. It does so purposefully, with reference to one of the most egregious “forgetting” of civil rights for African Americans, post-Reconstruction era.

Piraino’s work elegantly conveys a sense of muted history, the artifacts of which have an undeniable coldness. Her installations are less about what were, than what could have been, were history better remembered.