(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

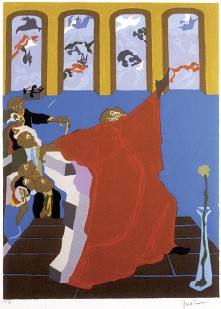

No. 5 from Eight Studies for The Book of Genesis ‘And God created all the fowls of the air and fishes of the seas.’

Under the curatorial savvy of Marina Pacini, the Memphis Brooks

Museum of Art has mounted the stunning and comprehensive exhibit “The

Prints of Jacob Lawrence, 1963 – 2000.”

Eighty-one lithographs, woodcuts, silk-screens, and etchings —

on loan from the Jacob Lawrence estate courtesy of New York’s DC Moore

Gallery — fill gallery after gallery with pure pigments, bold

shapes, sharply angled perspectives, and pitch-perfect storytelling by

Lawrence, the late Harlem Renaissance artist who took printmaking

to the level of masterwork and created a vision powerful enough to

speak to all people and all times.

You’ll find all of Lawrence’s best works here, including the

exhilarating and unnerving study No. 5 from Eight Studies for

The Book of Genesis, in which a preacher grips his marble podium

with his left arm while streaks of red flash from his right hand like

lightning. The preacher’s dark-red robe fills most of the silk-screen

as his parishioners gasp and crowd against the wall while water fills

their sanctuary and images of Genesis play across the alcoves and

stained glass windows.

At the center of the screenprint The Capture, from The

Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture series, Haitian revolutionary general

Toussaint rides a white steed and wears a cloak as deep red as the robe

of the preacher. Toussaint’s eyes are piercingly bright. His body leans

forward on the horse he rides straight toward the viewer. The print’s

pure-white and saturate-red color and the tall grasses that lick

Toussaint’s body like flames tell us his mission is full of passion,

danger, and purity of vision.

Lawrence tells story after story of courageous bids for freedom.

Harriet Tubman leads fugitive slaves north to freedom in Forest

Creatures, and Africans, being transported for sale in the slave

market, successfully commandeer a Spanish galleon in Revolt on the

Amistad.

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

The Capture, No. 17 from The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture series: ‘Toussaint captured Marmelade, held by Vernet, a mulatto, 1795.’

Placards accompanying these prints contain Lawrence’s reflections on

his life and worldview. We learn from these vividly written footnotes

that he moved with his family to Harlem at the age of 13, steeped

himself in books at Harlem’s Schomburg Library, and reveled in the

architecture and energy of the big city. This was the early 1930s.

While America was struggling through the Great Depression,

African-American creativity and intellectual thought was flourishing in

what came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. During those years,

Lawrence developed a passion for knowledge and social justice that

informed his life and art until his death in 2000.

The highlight of the show are the 22 prints in The Legend of John

Brown series, Lawrence’s undisputed masterwork. These are the

sparest, most abstract works of Lawrence’s career. They are also the

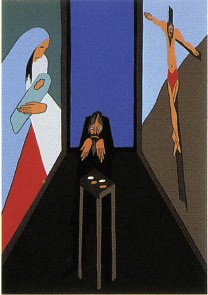

most poignantly apropos for our time. In screenprint No. 1,

Christ hangs on the cross back-dropped by what look like fast-moving

storm clouds or the wings and beak of a large raven or an omen —

readings that remind us Christ’s crucifixion is a dark drama about

government brutality, warring religious factions, and a friend’s

betrayal as well as the hope for redemption. Below Christ, a

figure in dark clothing turns his head down and to the side. This could

be one of Christ’s disciples, John Brown, or someone today making the

same tough choices, asking the same kind of life-changing questions: In

what shall I place my hope? To whom shall I give my

allegiance?

No. 1 from the portfolio The Legend of John Brown

In the placard next to the final image of the series, Lawrence

succinctly noted that, “Brown was found guilty of treason and murder in

the 1st degree and was hanged.” Instead of a storm cloud, like the one

that backdrops Christ in screenprint No. 1, the shape that

coalesces behind Brown’s body is a soft pale blue. Jagged in some

places, softly curving in others, the cloud looks, in part, like the

profile of a lion or other large predator with a gaping mouth and thick

strong neck. Its color and shape are fitting metaphor for the spirit of

a revolutionary who was both a fanatic and a saint, a man who resorted

to violence when all peaceful attempts to help the slaves were

thwarted.

While much of Lawrence’s art reveals what can be accomplished when

people work in concert with courage and conviction, The Legend of

John Brown series is a darker tale that plays out again and again

in a world where slave-trafficking still thrives and millions live in

refugee camps, in bondage, and in poverty. People in desperate

circumstances, The Legend of John Brown reminds us, resort to

desperate measures.

On a more positive note in screenprint No. 14, sharply angled

images of Mary holding the baby Jesus and Christ-crucified thrust our

point-of-view through a long and narrow room out into a piercingly blue

sky. Beyond ego, beyond narrow concerns — like Toussaint, Tubman,

and Christ — Lawrence inspires us to explore the big ideas, to

trust the redemptive power of love, and to make a difference.