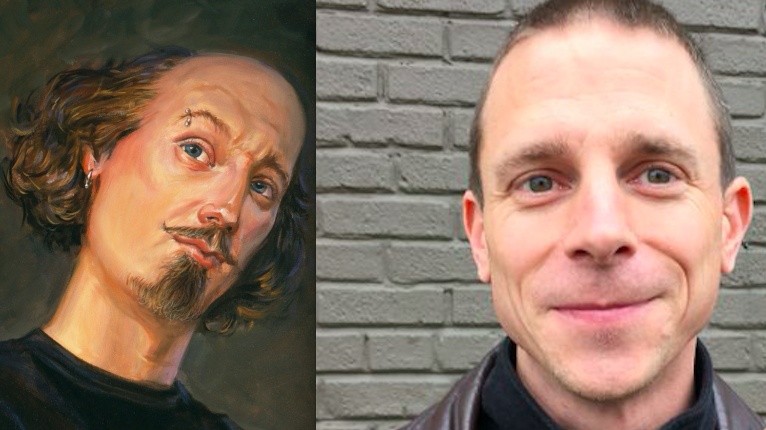

Shakespeare and Newstok

Rhodes College English Professor Scott Newstok has presented his first lesson to the incoming class of 2020, and is a Deusey: “How to think like Shakespeare.” It’s a witty critique of modern education practices that begins with a rather incendiary notion stated in clear, unmistakable terms.

But to me, the most momentous event in your intellectual formation was the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which ushered in our disastrous fixation on testing. Your generation is the first to have gone through primary and secondary school knowing no alternative to a national regimen of assessment. And your professors are only now beginning to realize how this unrelenting assessment has stunted your imaginations….You’ve been cheated of your birthright: a complete education.

In his address Newstok takes on several misconceptions about education, brushing away the waxy film of political ideology to reveal truths about the relationship between traditional models and meaningful progress. He does so using Shakespeare — the only named author in contemporary “common core” curriculum — and the kind of educational models he’d have encountered as a student.

Building a bridge to the 16th century must seem like a perverse prescription for today’s ills. I’m the first to admit that English Renaissance pedagogy was rigid and rightly mocked for its domineering pedants. Few of you would be eager to wake up before 6 a.m. to say mandatory prayers, or to be lashed for tardiness, much less translate Latin for hours on end every day of the week. Could there be a system more antithetical to our own contemporary ideals of student-centered, present-focused, and career-oriented education?

Yet this system somehow managed to nurture world-shifting thinkers, including those who launched the Scientific Revolution. This education fostered some of the very habits of mind endorsed by both the National Education Association and the Partnership for 21st Century Learning: critical thinking; clear communication; collaboration; and creativity. (To these “4Cs,” I would add “curiosity.”) Given that your own education has fallen far short of those laudable goals, I urge you to reconsider Shakespeare’s intellectual formation: that is, not what he purportedly thought — about law or love or leadership — but how he thought. An apparently rigid educational system could, paradoxically, induce liberated thinking.

I’ve only quoted the set up. The good stuff’s all in the body of the address, which was published in the Chronicle of Higher Education, and which I heartily encourage you to read.