The calls come at all times of the day. “Hi, this is Dana. Hope you’re having a great day. I was reaching out to see if you had any interest in maybe getting an offer on your property. My wife and I are buying homes in the area, so we thought we would shoot you a call real quick to see if you have any interest. We can pay cash. …”

“Hi, it’s Ashley again. I gave you a call a couple of weeks ago, and I wasn’t able to reach you. I wanted to reach back out and see if you’re interested in getting an offer on your property. My husband and I have been buying homes in the area, and just wanted to see if it’s anything you were interested in. …”

The callers know your name, your address, and seemingly how much your property is worth. When it’s not calls, it’s text messages: “Hi, Christopher. My name is Angela. I was reaching out to see if you were interested in getting an offer. …”

Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis

Printed and hand-made signs pop up at intersections.

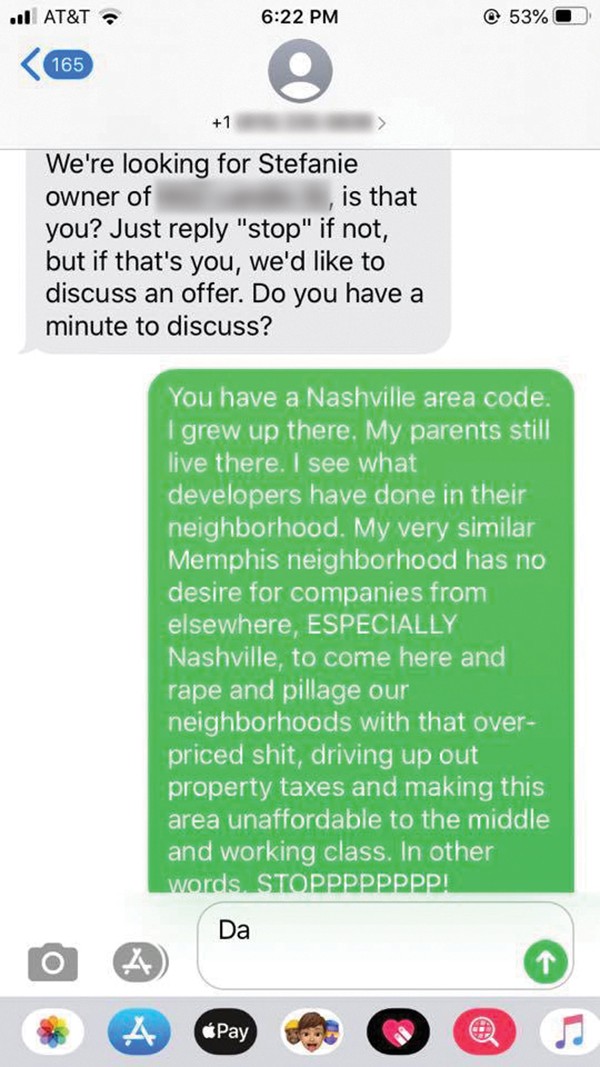

People all over the Mid-South have been getting these calls for years, but in recent months, the volume has seemingly accelerated. A Facebook query yielded 115 comments from people saying they have been receiving unwanted calls, texts, letters, and postcards from sketchy strangers wanting to buy their homes. “I get them about once a week,” says Katie Mars.

“They call me for my mom’s house,” Cristina McCarter says.

“Yes, many robocall voicemails faking as if they are individual calls from a local couple just happening by my property and want to know if I want a cash offer. I don’t know how they got my cell, but I often admire their creativity,” says Paul Morris.

“I get calls, and I don’t even own a home,” Mac Edwards says. “I think they work with the auto warranty people.”

“I got one recently where they said, ‘Hey, neighbor. I just moved into your neighborhood! Thought I’d say hi! By the way, would you like to sell your house?'” Alex Greene adds.

“I asked how they got my number, and they didn’t reply,” says Dana Gabrion.

“I had a guy call multiple times. He gave me attitude in messages because I wouldn’t call him back. Another one got upset with me when I asked him how he got my number when he called to ask about the house,” says Gabriel DeCarlo.

“Every day for our house, and multiple times a day for our rental property,” Josh Campbell says.

“Every few weeks I get about 20 calls and texts telling ‘Vernon’ they’d like to buy his house,” Cecelia Dean Ralston says. “This has been going on for five or six years. No idea who Vernon is, and I’ve had the same number for 15 years. I’ve told dozens of people it’s not me, but they don’t care.”

Meriwether Nichols is a Memphian who now lives in Sante Fe, New Mexico. She uses her former home in Midtown as a rental property. She gets calls and texts about it “nearly every day. They are from somebody who is a real person, at least from what I can tell, and they use a first name. They do not identify a company.”

Inevitably, the callers deny being realtors and claim to be mom-and-pop real estate investors. “They make it sound pretty folksy. And sometimes, if I’m of a mind to, I will call them back or I will text them back and say, ‘What is your purpose? What’s your intention for this property? Are you an investor? Are you a flipper? What company are you with?'”

Nichols says answers are rarely forthcoming, but once she got a person calling from a number in the 901 area code to admit he was actually in Bozeman, Montana. “You skiptraced my number through property tax records and called me on my personal cell phone in the middle of a pandemic,” Nichols told the caller. “This feels awfully predatory.”

Cold calls and unsolicited text messages are among the tools used by buyers relying on data-mining.

Who is making these cold calls, sending unsolicited texts, and flooding neighborhoods with postcards filled with identifying personal information?

“I don’t think this is realtors who are doing this,” says Kathryn Garland, president of the Memphis Area Association of Realtors. “My suggestion to any homeowner who gets a call like this is to consult their realtor, because we’re the ones who are the experts in our field. We can tell you what the value is of your home and make sure you’re not leaving money on the table.”

Anyone can call themselves a real estate investor, Garland says. “But a realtor is a licensed real estate professional who is part of the National Association of Realtors and abides by a code of ethics.”

Realtors have a fiduciary duty to protect the interest of their clients. “So it’s a standard of care,” Garland says. “A ‘real estate investor’ might, with their own money, buy and sell real estate, but they can’t broker it for a consumer, necessarily.”

Finding leads is always problem No. 1 in real estate, as in any job related to sales. Cold calls are a tactic to create leads. “There’s nothing inherently wrong with doing this, other than it annoys people,” Garland says. “It raises the question of, ‘Why are you calling me?’ There’s gotta be a scam here, you know? I don’t necessarily think that that’s always the case.”

Traditionally, a property owner wanting to sell will contact a realtor to put their home on the market. Cold callers are looking to short-circuit that process and cut out the realtors. Garland says the current flood of solicitations is a reflection of the state of the Mid-South market: “I will say, this is about inventory being low. That’s basic supply and demand. And so, when supply is short and demand is high, it drives prices higher. That’s why we’ve had such great return, year over year — especially this year. I think we’re like 19 percent over last year on average wholesale price. And we’re in the middle of the pandemic. My point is that investors — they may be paying cash or whatever — but they don’t always pay top dollar for things.”

Garland was one of the few real estate professionals willing to talk on the record about this issue. No licensed realtors I spoke with admitted to cold calling or texting. “I think it’s tacky” was a common response.

“That’s not the first contact I want to have with a client,” says one realtor.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one veteran real estate professional, whom we will call “B,” was more blunt. “Look, it’s hard to make money in real estate. It’s like going to grad school.”

There are two groups making these calls, B says. One group “doesn’t know what they’re doing.” The other group is “massive corporations gobbling up single-family homes.”

Both groups are driven by a common incentive: massive amounts of money pouring into the speculative real estate market from national and international investors. Take a worldwide pandemic, a borderline depression, soaring unemployment, and a political situation that is, to put it euphemistically, fluid, and that adds up to unprecedented uncertainty. The stock market, a traditional place for speculative capital, is being propped up by trillion-dollar influxes from central banks. “Everyone is terrified,” says B. “They’re trying to find something to believe in.”

That “something” is real estate, traditionally the safest of investments. Newbies looking to get rich quick in the hot market are flocking to classes taught by real estate “gurus,” B says. Some of these gurus are telling their students that, while traditional methods of generating leads can have only a one to three percent return rate, data mining companies claim their lists of property owners can deliver up to 40 percent returns. While it is true that a realtor will get you the best deal for your home, there are situations a realtor won’t touch. Maybe an inherited property has too much deferred maintenance, and the owner cannot afford to bring it up to code. The cold callers may be vultures, B says, but “vultures clean stuff up.”

Chris McCoy

Chris McCoy

Engaging with cold callers can be a risky business. Grant Whittle has been inundated with inquiries about his rental property, a Midtown duplex. “Whenever I get a text message, I write them back and I say, ‘I want $190,000, as-is, no questions asked. You pay all the closing costs.’ I think that’s sort of fair value for the house. They normally never write me back because they want to pay like half that.”

One day last December, someone did respond. “This guy texted me back and said, ‘Well, let me check.’ And I was like, ‘Whatever.'”

The real estate investor unexpectedly said yes to Whittle’s price and conditions, drew up a contract, and put down earnest money. “I still, even at that point, was thinking, ‘I bet this isn’t going to work out.'”

Then the investor asked to inspect the house. “And I’m thinking, have you not even driven by it? Cause I think, in general, they don’t,” says Whittle.

The day after the inspection, the investor called to say he couldn’t go through with the deal at $190,000. “And I was thinking to myself, I wouldn’t have ever thought you could either, except that you were all insistent on it. Maybe he’s just really green and stupid.”

Despite their contract, the investor offered $110,000. Whittle refused. “And then he actually called me again about it about a week later and said, ‘Are you sure you don’t want to sell it for $110,000?’ I was like, ‘No!’ There are obviously people out there who have on their hands a house that is a burden for them. They don’t want it anymore, and it’s not in very good condition. It would be hard to sell, and they just want to get rid of it. Okay, fine. But I’m not that person.”

Many of these real estate “wholesalers” do not actually have the capital on hand to buy a house in cash. When they get a hit, as in Whittle’s case, they will try to get the target home under contract for a certain amount. Then they will use the contract’s 30-day duration to shop the property around to their list of investment contacts to sell it for more than the contracted price. If they can’t make the upsell (30 percent or more), they will simply let the contract expire, having effectively taken the property off the market for a month.

Steve Lockwood will soon be retiring after 18 years as the head of the Frayser Community Development Corporation (CDC). Lockwood has been in the housing game in Memphis since the 1970s, when he helped take Cooper-Young from a decaying wreck to one of the most desirable neighborhoods in Memphis.

“Homeownership on the macro scale is simply good for neighborhoods,” he says. “Because people are not so much financially invested, which they are, but they’re also personally invested. No one is against rental properties — we’re landlords, too. But there’s pretty strong data that shows that if you’ve got a reasonable percentage of homeowners, the neighborhood is simply healthier, the communication between people is better, neighborhood responsibility works better, and yards get cut.”

Lockwood says during the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, “This neighborhood was the absolute ground-zero laboratory for predatory lending.” After the crash, a wave of foreclosures ripped through the neighborhood. “Frayser led the state in foreclosures for about 10 years straight.”

Black families, which make up about 85 percent of Frayser, suffered foreclosures at approximately seven times the rate of white families. “Homeownership has not always been the great benefit for Black families that it’s supposed to have been.”

Many of those foreclosed homes never resold and were simply abandoned. Under Lockwood’s leadership, it’s been the mission of the nonprofit Frayser CDC to purchase and rehab blighted properties, rent them to low-income Frayserites, and help as many of them as possible to become homeowners. The market conditions in Frayser make it irresistible to wholesalers and cold-callers. “Our home prices right now are 37 percent of the Memphis area median, and our prices are rising faster in general than any other neighborhood in the city.”

The Frayser CDC owns about 130 properties, which means they are inundated with unsolicited offers. As I spoke to him on the phone, Lockwood pulled 15 postcards out of his trash can — about one day’s haul. “Some of the postcards are real sophisticated,” he says. “They’ve got a picture of your house on it and it says, ‘Is this your house? I’m interested in buying it. Call me up.’ They’re trying to give the impression that they paid some individualized attention to you, in a sense. But obviously they’re just data mining. That allows them to plug in thousands of addresses, get photos off of Google Earth, and punch out these slick-looking postcards. There’s an industry of people who do this for a fee. It’s pretty specialized.”

Lockwood says the wholesalers have made it more difficult for his organization to find houses. “We’re steadily trying to buy blighted houses, fix them, and put them back into service. These days we mostly sell to homeowners. But it’s gotten very hard to find houses because these big boys are playing this game and keeping all the good ones for themselves. The real real estate phenomenon going on in Frayser right now is that there are people snatching up all the houses, fixing them up, and then reselling them to investors in California. Then they keep the rental contract. And that’s really where they make their money, on the management side, moving forward.

“These people are not all monsters — which is to say, some of them do good work on the house, put families in, and are good managers of the houses. What they have done is contributing to lowering the amount of blight in the neighborhood. I’m not completely cussing these guys. But they are not contributing to homeownership. And in fact, they’re locking these homes, long-term, into non-local ownership. So I’m not completely applauding them, either. And some of them are predators and really bad people.”

In order to compete with the data-driven, investment-financed, rental business, Lockwood says the Frayser CDC is looking into adopting the direct-mail model. “We’re very businesslike, but we’re mission-based do-gooders in this neighborhood. And we mean that. So we’re trying to learn to play this game on behalf of homeownership, and the good of the neighborhood, rather than how it’s working out now.”

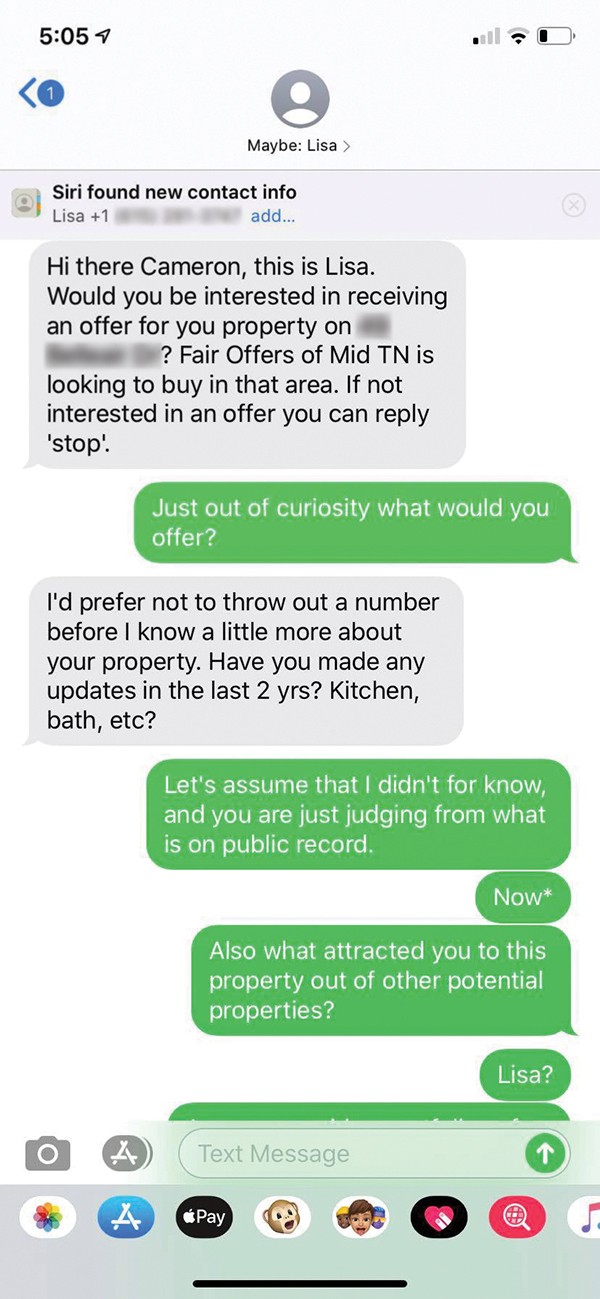

I attempted to trace several calls from numbers given to me by respondents to my Facebook post. One call to Memphian Cameron Mann claimed to come from a company called Middle Tennessee Home Buyers. I reached a person at the company in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, who identified himself as Jeremy. He denied his company was behind the call. “We made a decision that we’re not going to do that.”

Returning one call from the 901 area code got me a person named Andy who said he was in Scottsdale, Arizona. When I returned calls from voicemails received earlier this year, the numbers had all been disconnected.

Last Thursday, as I was at my desk working on this story, I got a voicemail. “Hey, this is Mark, giving you a call. I was driving in the neighborhood and I noticed your house. I was looking to see if you might ever consider an offer for the property, I pay cash and all closing costs, and I’m close right now.”

I returned the call within five minutes and was connected to Eric from the National Home Buying Company. He was in Nashville and said his company bought properties all over Tennessee. He claimed his company did about 20 deals a week. When I asked for an offer on my home, he asked me about the condition of the roof and the HVAC system. He quoted me a price that was 30 percent below the current estimate on zillow.com. When I revealed I was a reporter, he became flustered. Was Mark — his colleague who claimed in the voicemail to be driving by my house 10 minutes ago — real? Of course he was, Eric said. When I asked to arrange a meeting with Mark, Eric said he would pass along the message. Mark never called.

Eric, it turned out, was unusually polite. I returned a voicemail from “Ashley,” who claimed she was buying houses with her husband. I got a person who identified himself as Jake Taylor, who said Ashley was currently out of the office “to pick up the baby.”

“Typically, we bring the most value to homeowners who are looking to sell their home, but not necessarily wanting to invest any more money into it, and then have to go through a realtor and show it a bunch of times, and then pay commissions and fees. We’ll just come in and buy it as-is,” Taylor said.

When I told him my address, Taylor said, “I love that little area.” Then he asked me where I was planning to move to.

“I’d rather not tell you,” I said.

“Okay, well, fuck you too, then,” he replied.