The first time I rode a train was from Chicago to Memphis. I’d made a car trip north with my aunt who had been visiting here and we gave little thought to how I might get back home. It turns out the train was the most convenient and inexpensive way to travel. So on the appointed day we made the drive from the suburb where she lived into the city and sprawling, spectacular Union Station; we said goodbye and I boarded the train alone. I was 13 years old.

It was an important milestone in my life and one that most kids won’t get to enjoy, not these days, anyway. It was also the beginning of my love affair with train travel. I haven’t done as much of it as I would’ve liked to over the years, but I have traveled back and forth from Memphis to Chicago a number of times, as well as round trips from Memphis to New Orleans. My wife and I took the City of New Orleans for our honeymoon, and years later I took my then-3-year-old son to Chicago.

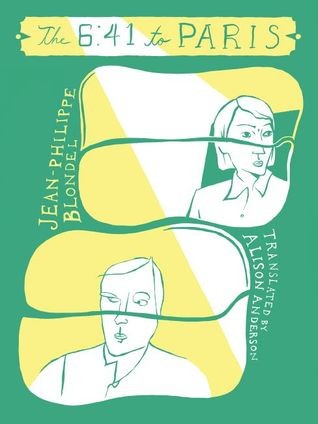

Travel and literature tend to be intertwined. There is little in plot structure more enduring or captivating than a book that takes the reader on the road. In The 6:41 to Paris (New Vessel Press) by Jean-Philippe Blondel (translated to the English by Alison Anderson), the two main characters travel from Troyes, France, to Paris on an early morning train. While the car is full of strangers pushed together for the two-hour ride, some doing work, most trying desperately to mind their own business and be left alone, Cécile Duffaut and Philippe Leduc find themselves seated side by side.

These two know each other. Their history goes back more than 20 years when they had a four-month love affair that ended badly. It ended very badly and, though they don’t speak, we are clued into the whole story through Cécile’s memories and then, in turn, Philippe’s memory of the same time period. “She doesn’t remember me,” Philippe thinks to himself. “So much the better, in the end. I have to keep one thing in mind: most people have a ‘delete’ key which they will press at a given time, when their brain is about to overflow after all the misunderstandings and betrayals, all the hurt and disgrace . . .”

At times, it seems, this train is powered on depression. Cécile and Philippe have both changed, of course, and though the characters have moved on from their failed relationship, neither is particularly happy with where their lives have led them.

The Philippe of memory was a shallow man, at best, who describes the Cécile of his memory as “nothing to look at, with her ordinary face, slightly curly shoulder length hair, and clothes that came straight from a discount superstore.” And yet he has become nothing much to look at, this trifling man who works at an electronics store selling TVs and DVD players. He is the divorced father of two children who has gone soft, his once-impressive physique giving way to age.

Cécile, in the seat next to him, thinks to herself, though that inner dialogue reads as though shouted into his ear: “I’m talking to you, Philippe. This is a declaration, from twenty-seven years away, this is a

declaration even though you don’t look at all the way you used to, even though no one notices you anymore, and you’ve sunken into the anonymity of your fifties where we seem to go all gray and hazy — hardly anyone notices, except for the occasional cruel comment: ‘He must have been a handsome man,’ ‘I’ll bet she was stunning.’”After the end of their relationship during a trip to London, Cécile, by all rights, should have crawled away to live the life of Havisham. But she didn’t and is, instead, a wife and mother who runs her own business that is on the verge of taking off across Europe. She is on her way home after a weekend spent with her parents as they decline ever more quickly into their ages. “I thought about old age. About change. About the boredom of repetition.”

At 13 years old, for 10 hours, I was on my own on that train. I was independent and, instead of being scared (I was an anxious kid), I felt elated and light. Philippe, middle-aged now just as I am, considers travel and the larger sense of broadening horizons while on the train to Paris: “We were growing up in an era when flying was still the exception, and to wake up in New York or Tokyo would have seemed beyond our reach. Computers were at the experimental stage, and no one could imagine that one day we would no longer need phone booths. On the other hand, the future seemed wide open, and the planet, eternal.”

Despite their stations and the necessarily maudlin voices that are, for the vast majority of the time, limited to their own heads, the book is fascinating and fast moving, and the characters’ volley of memories

render them well-rounded. There is the brief glimmer of hope that travel affords all of us, the thought that maybe we won’t get off at the next stop, that maybe a new life will be waiting someplace else, and that maybe the person sitting next to us is who we were meant to be with all along.