Was it Emily Post or Miss Manners who addressed the topic of farting at dinner? Whichever maven it was, the advice went something like this: ghastly, mostly involuntary embarrassments should be ignored by smeller and feller alike. I mention this even though all the important farting in Evan Linder’s new play, Byhalia, Mississippi, happens somewhere other than the table, because his play is a comedy of manners. It illustrates, among other things, how easy it is to go “nose blind” to the noxious things we tolerate and even pardon in the name of good taste and breeding.

Also because the show — good as it is — may have some nose blind spots of its own.

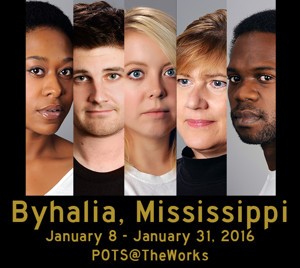

Byhalia, Mississippi plays really, really well. I caught a fever for the work Linder does with his creative partners at The New Colony when Rhodes College produced The Warriors, a staged collection of interviews with survivors of the mass shooting at Westside Middle School in Jonesboro, Arkansas. The Warriors wasn’t just good theater. The New Colony’s stubborn refusal to sensationalize tragedy felt very nearly groundbreaking. I didn’t love Linder’s comedy Five Lesbians Eating a Quiche, but I liked. A unique theatrical voice was clearly emerging. His latest play is the most impressive so far. Still, as previously noted, there were things that got under my skin — Things difficult to talk about without dreaded spoilers. So…

I’ll dispense with plot summaries and start by underscoring some things the play gets really, really right.

Byhalia works because the characters and their relationships are true to life. It’s fiction, but if you’ve spent any time in the Memphis or the surrounding region, you’ll recognize every person on stage. In that regard it reminds me a lot of The Warriors where actors played real people. Linder knows his subject matter. He may have set up shop in Chicago, but more pertinent facts may be discovered by clicking this link, and scrolling down the page until you see THE PICTURE. You’ll know it when you see it. This is a guy who gets us in ways only a few other writers really do. He gets us in ways that compliment and counterweight the romantic firefly-infested stories we like to tell ourselves.

Jillian Barron, who plays Laurel, Linder’s female protagonist, is especially strong here. Barron, it seems, can do no wrong. She was one of the more fantastic things about Jo Lenhart’s fantastic As You Like It at Theatre Memphis. She followed that with an award-worthy turn as a talky millennial in Rapture, Blister, Burn in the same space. Her Laurel doesn’t always make good choices but she’s always trying (sometimes failing) to choose better. She owns her worst mistakes — eventually— and she learns from them, kinda. She’s flawed but decent, and constantly, awkwardly evolving. It’s a terrific role on the page and Barron wears the character like school colors.

Jim, Linder’s philandering male protagonist, is what passes for “post racial” in the American South. Evan McCarley plays him as a laid back good ol’ boy who can’t understand why Ole Miss abandoned Col. Reb, but “some of his best friends “… etc. The play trades old Jim Crow stereotypes for new Jim Crow stereotypes so Jim, an unemployed construction worker faced with the prospect of taking a job at Walmart, isn’t frothing at the mouth because his wife slept with an African-American. Sure, he immediately assumes the worst of his best friend Karl, but, end of day, the baby’s blackness is only an issue because it’s an indelible mark of Laurel’s infidelity. It makes her mistakes worse than his own because her mistakes can’t be swept under the rug. Pop culture’s usual cartoon rednecks who hate on women and do racist things because they’re cartoon rednecks have been replaced here by something more banal. And more awful. Something that loves you like your mama. Something that hides behind heritage, embedding itself in values and institutions where nobody will look because looking is rude.

But what about that Nativity scene conclusion, really? The one where the affable, adorably inept white people (babe in arms) get something close to a happy ending? Maybe it’s not storybook perfect, but is does call to mind the holy family in its hopefulness. The play’s pivotal couple is reunited. They don’t leave town ahead of scandal (or worse). They’re going to be okay. The troublesome brown baby at the center of their marriage crisis gets to keep one actual parent while young Jim learns to embrace his recent shame as though it were his very own flesh and blood.

Isn’t “white father learns to love non-white baby,” an awfully patronizing (from “pater”) plot point?

I opened my original, and generally positive review with a question about closure. Is it for caucasians only? The play ends with Jim and Laurel doing some variation on what audiences will experience as “the right thing.” But outcomes are less certain for Byhalia‘s remaining African-American characters. They remain caught up in incidental counter-narratives about diaspora and sperm donor dads. On one hand Byhalia, Mississippi refines images of white racism while seeming to affirm unfortunate African American stereotypes regarding cheapness of life and hyper-sexualization.

Absent fathers are a staple of the American family epic and like Tennessee Williams’ Glass Menagerie, Byhalia, Mississippi is sometimes a haunting portrait of a man who isn’t there— The story of a man taking no responsibility for his progeny. This invisible dad does pay an indirect price exacted by his (angry) status conscious wife, Ayesha when Laurel runs a suggestive birth announcement in the newspaper. Ayesha predicts a coming scandal that her husband, a small town high school principal, can’t endure. She persuades her flatulent, philandering spouse to leave his his job and relocate to Jackson — which is conveniently where she always wanted to live anyway.

Ayesha offers Laurel $4,000 to get out of town. It’s enough to relocate, but in the absence of meaningful sustained support, the bargain becomes little more that a payment for her husband’s extra-marital sex, priced at a rate that buys discretion. Days later Ayesha and the invisible daddy put the brown-ish baby, Byhalia, and whatever those two things might mean in the rearview mirror, and drive away.

Jessica Johnson’s Ayesha is a force of nature. The actor finds dignity in disgust. She finds grace, even in a Jerry Springer moment where she goes all Martin Luther and nails a message to Laurel’s door.

Karl, who’s known Jim, Laurel, and Ayesha for most of their lives, may be Linder’s most interestingly developed character. His ending is certainly the play’s unhappiest and Marc Gill — another actor who can do no wrong — nails it. Gill is very good at emphasizing the things his character doesn’t say, and sharing perfectly framed glimpses of the things he wants to keep hidden. Ayesha calls him an “uncle,” and the word lands hard with double meaning. Karl and Jim are best friends, co-workers, and serial roommates. But the relationship is out of balance. there’s a dishonesty between them that only becomes apparent when Jim assumes the worst. And there’s dishonesty on top of that.

Karl’s pants are down when we meet him. He’s been caught whacking off to pictures on his laptop that he really doesn’t want anybody else to see. That kind of introduction lingers.

Byhalia, Mississippi ends with Jim and Laurel free at last. They’re free— momentarily, at least — from Laurel’s hateful mom (Gail Black in top form).They’re free(ish) from the bonds of other people’s stupid rules. They’re free to laugh. They’re free to feel good bout naming their kid for a hate crime victim they’d never heard of until his memory was invoked to shame Laurel. They’re free to sit on the roof and smoke pot while the little one sleeps. The are also free and isolated from all their black friends. And all of their black “friends.”

Talking about these sorts of things can be tricky. Hopefully nobody involved will experience this supplementary review as an accusation of bad faith. I liked Byhalia, Mississippi. As an evening of entertaining theater, I can recommend it. But no matter how hard I try, I simply can’t experience it as a finished piece of work. And if it is finished, I can’t experience it as the hopeful work I believe it’s intended to be.