Galileo goes before the inquisition for expanding the Copernican heresy.

What’s the deal with 1616?

Well, Shakespeare died in England, obviously. Cervantes kicked the bucket in Spain. But celebrity death’s not all that interesting, in and of itself. 1616 was a time of enormous contradiction. Old dynasties crumbled while a new world was being plundered. The Earth was growing larger and smaller at the same time. A slave trade and smallpox flourished in the places where where sea monsters once appeared on flat world maps. Science advanced brave new ideas while the church doubled down on its authority and witches were hunted with renewed fervor. Globalism was in its infancy, as were global corporations. Applied arts and sciences found themselves at odds with establishment values.

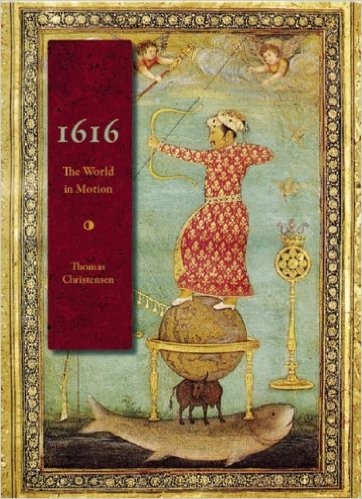

Thomas Christensen‘s book 1616: The World in Motion is an entertaining and enlightening romp through the early modern era, when Spanish Galleons delivered silver from Acapulco to China and exchanged it for silk and spice. Christensen’s a first rate storyteller, with a curators eye for art and artifact. He’s also the keynote speaker for the 1616 Symposium at Rhodes College this week. Although it’s been made possible by the Pearce Shakespeare Endowment, the symposium uses Shakespeare’s death as a pretext to assemble scholars from different disciplines to discuss a world that was, quite literally, on the move.

Louise Bourgeois, the Royal Midwife

Christensen’s book covers a lot of ground. In less than 400 heavily-illustrated pages he touches on a little bit of everything from major world events to a power struggle that escalated between a French midwife, and the king’s physicians because the latter group had, “No knowledge of the placenta and the womb of a woman, either before or after her delivery.”

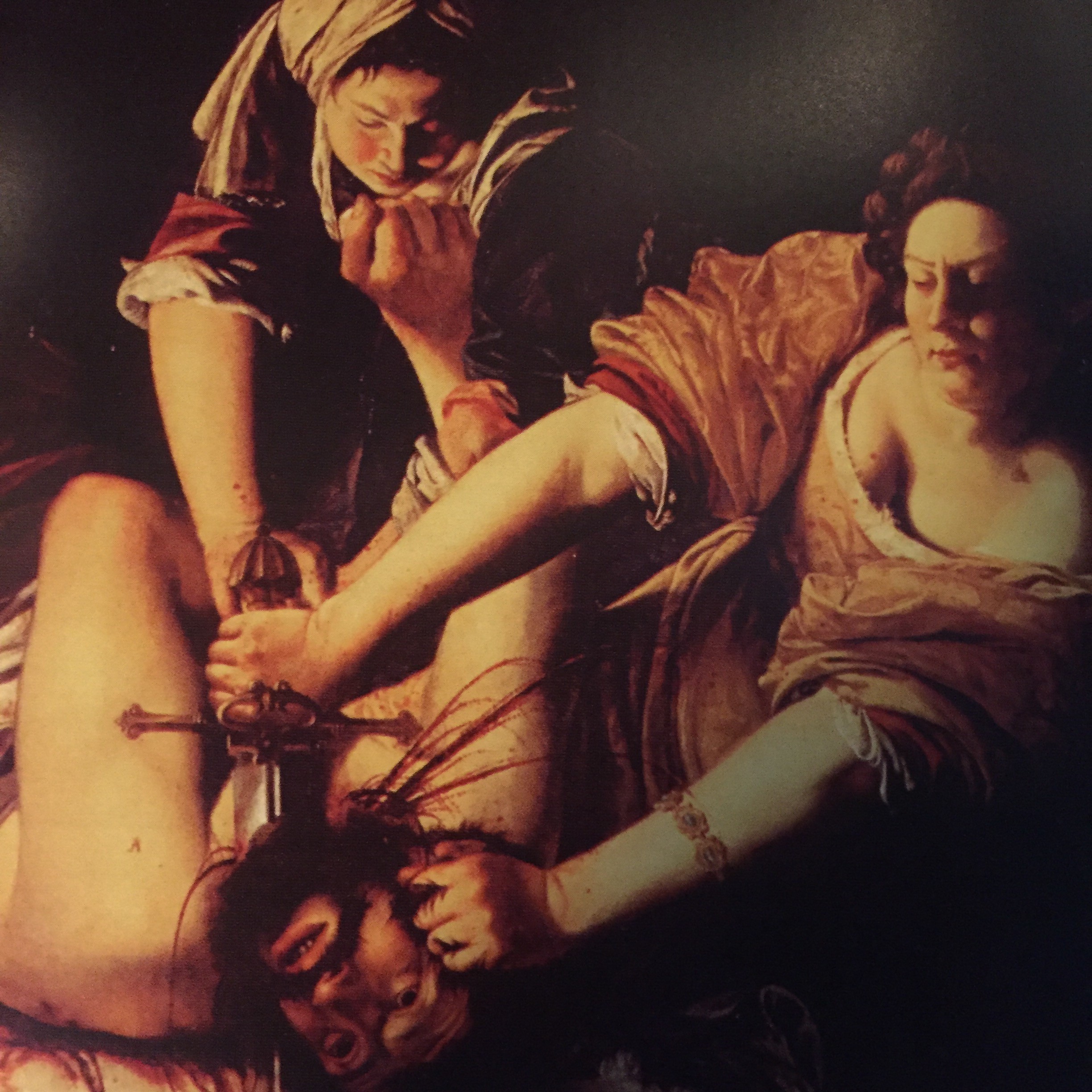

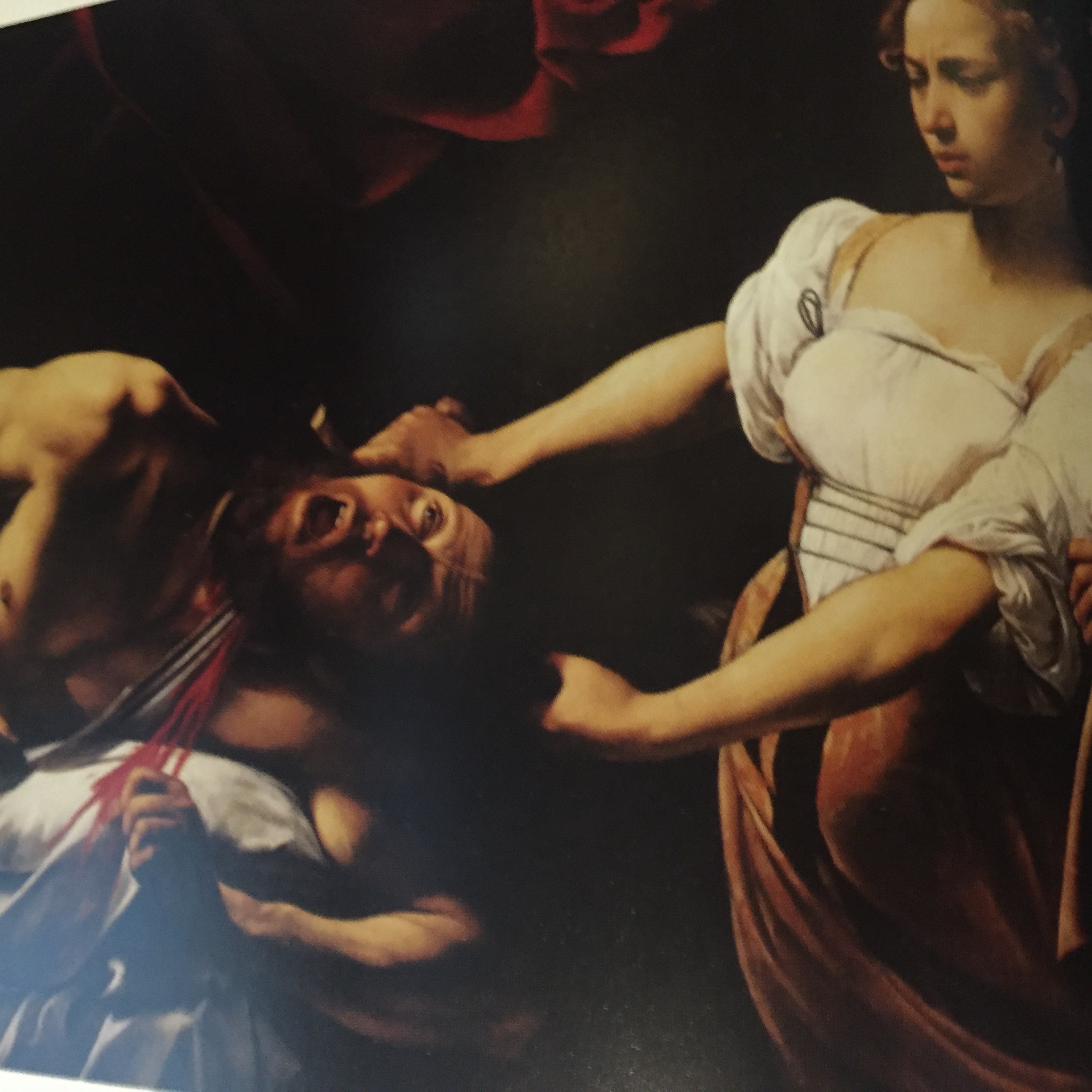

“Shakespeare’s Sisters,” a chapter devoted to women in 1616, is especially fascinating. More “rational” views of the natural world had curious consequences. Witch hunting, for example, had once swept up equal numbers of men and women. By 1616 accusations were leveled primarily at older women who were more likely to be herbalists, and keepers of folk traditions. Christensen elaborates on reasonably well known stories about Pocahontas‘ visit to Europe, the reign of Nur Jahan over the Mughal Empire, and the trials and artistic triumphs of baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi. My favorite part, however, is Christensen’s juxtaposition of the life of two crossdressing women: Mary Frith (AKA Moll Cutpurse), a pipe-smoking pimp known as the “Roaring Girl,” and Catalina de Erauso, a Basque soldier who aided in the conquest of the Americas, and was later given special dispensation by the pope to dress in men’s clothing.

Erauso, who first dressed as a man to escape life as a nun, served as the right hand man to her brother who never recognized her. She was eventually transferred to a heavy combat zone after the siblings came to blows over another woman.

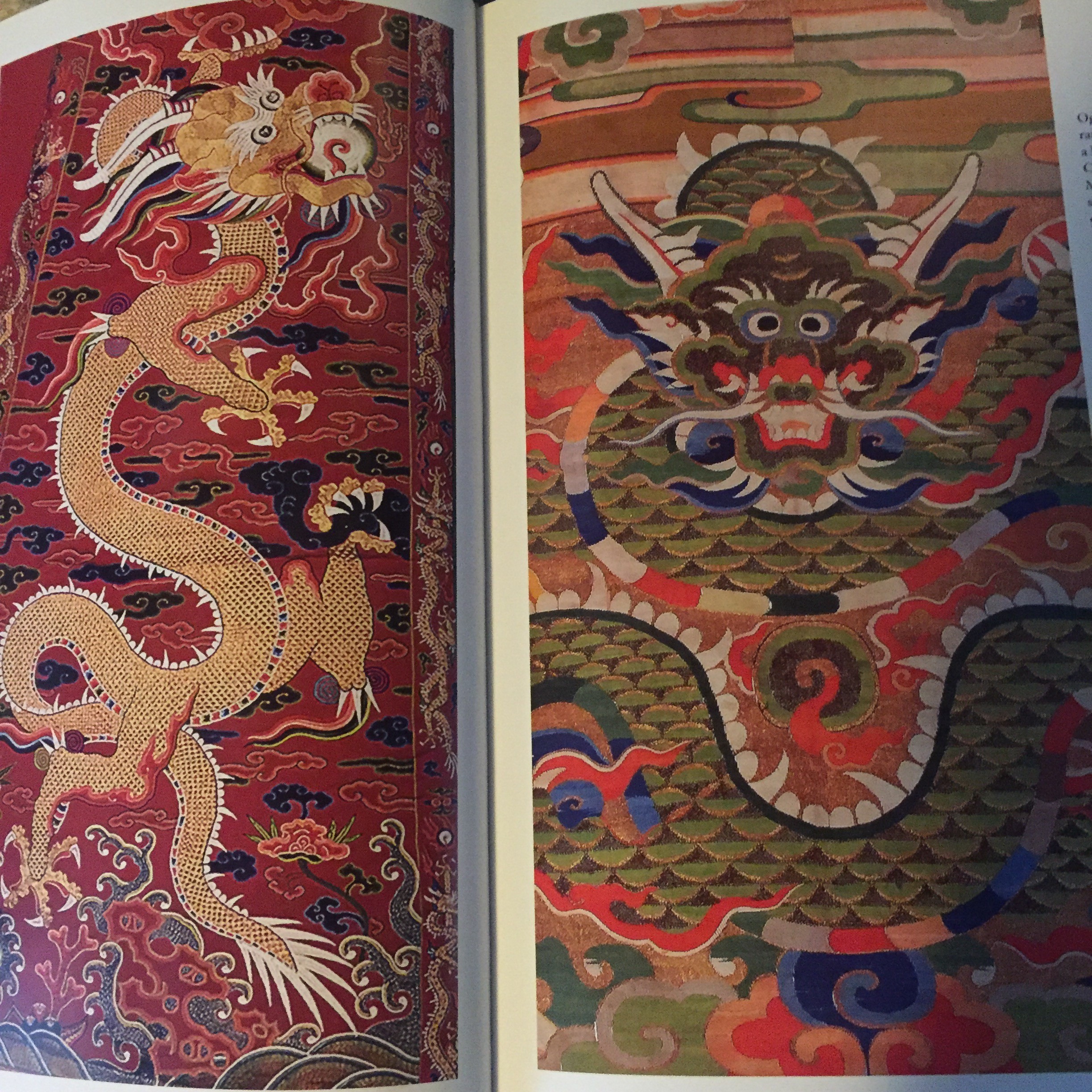

Gorgeous double-paged spread from 1616: The World in Motion

As far as Shakespeare is concerned, he was quite the innovator in his day, but it would be another hundred years before his Romantic makeover as the great lion of Western literature. As his fame grew in the 19th and 20th centuries, the man himself became harder and harder to see. Like Rhodes professor Dr. Scott Newstok explained in a recent interview for Memphis Magazine, the “fixation on Shakespeare occludes the way he actually worked.”

To that end the 1616 symposium doubles as a reverse-engineered portrait of Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi.

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Caravaggio.