I’ve started to become suspicious when someone points and says “This is what America is all about” or “this is not America.” America is many things. Americans wrote: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Americans also owned slaves — and later, freed slaves. America is a nation of immigrants that erected a statue welcoming the tired, poor, and hungry masses yearning to breathe free. Americans have also looked down on, at various times, Irish, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, Cuban, and Hispanic immigrants. America is, as the bad term paper cliche goes, a land of contrasts. Because America is made up of humans, who are themselves a mixture of good and bad, the American identity is always a tug of war between extremes.

From 1968 to 2002, one of our perpetual tug of war’s strongest pullers for good was Fred Rogers. He was a Presbyterian minister from Pennsylvania who fell in love with television, and saw in it a potential to do good on a vast scale. His TV show, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, started on a Pittsburgh area educational television station in 1968 and became PBS’ first hit. As one producer puts it early in the documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Mr. Rogers’ show was the exact opposite of everything conventional wisdom held was “good TV.” The sets were cheap, the puppets nowhere near Muppet levels of sophistication, and there were often long stretches of silence. And yet it became a cultural touchstone, thanks to the steady magnetism and stalwart humanity of its host.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is helmed by Morgan Neville, one of the finest documentary directors working today. He won the Best Documentary Oscar in 2013 with his film about backup singers, 20 Feet From Stardom, and last year he shared an Emmy with Memphian Robert Gordon for Best of Enemies, the story of the epic political debates between William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal during the 1968 election season. (Neville’s new film also boasts a Memphis connection: composer Jonathan Kirkscey provides the score.)

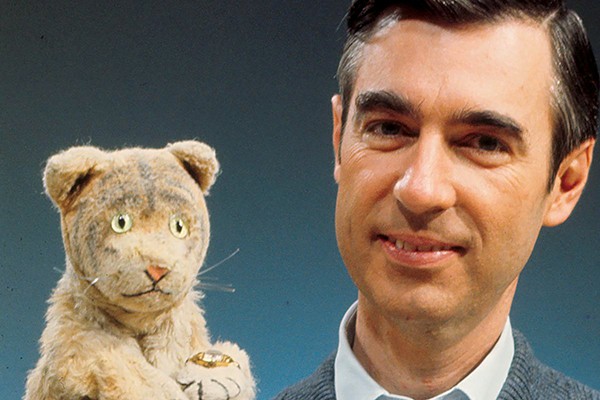

Daniel Tiger (left) and Fred Rogers, star of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood

Documentaries are always judged first by their subject, and Neville has a knack for choosing exactly the right ones. A master of documentary structure, he makes the case for Rogers’ continued relevance right out of the gate. Launched in 1968, during the most violent period of the Vietnam War and the rash of political assassinations in America, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood never shied away from wrestling with tough questions. During its very first week, there was a storyline where King Friday XIII wanted to build a wall around the Neighborhood of Make Believe because he was frightened of change. After Robert Kennedy was killed, Rogers did a week of shows teaching children how to deal with death.

The most electrifying moment in the film comes when Rogers is asked to testify before a Congressional committee hearing debating the future of PBS. His unpretentious eloquence brings everyone in the room to tears, including the senator who is there to grill him for wasting $20 million of taxpayer money on kid’s shows. Through it all, Rogers’ uncanny talent for connecting onscreen shines through as he makes friends with everyone from cellist Yo Yo Ma to KoKo the gorilla, who signs “friend” and “love” at the TV host.

You can tell a lot about a person by the quality of his enemies. Rogers was a lifelong Republican who advocated for an “open, accepting Christianity.” During the early years of Fox News, Rogers was routinely attacked as a decadent influence whose doctrine of radical compassion had raised a generation of soft liberals. When he died, his funeral was picketed by the notorious hate group Westboro Baptist Church. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is what you would call a warts and all documentary — or at least, you would call it that if its subject had any real warts to expose. At various points during the film, the people who knew and worked with Rogers say that he was exactly the same person offscreen as onscreen, thoroughly kind and empathetic to a fault. The worst thing Neville can come up with in the interest of balance is that, toward the end of his TV career, he started to identify more with the grumpy King Friday XIII than with the meek Daniel Tiger. I guess power really does get to everyone eventually.