St. Francis Elevator Ride, i.e. designer and artist Josh Breeden, makes digital collages that look roughly like what your grandmother might have seen if she took acid and spent a long time exploring her 1960s kitchen. Tequila-sunrise-tinted backdrops create a ground for bouquets of metallic machinery, while illustrative body parts float somewhere in the natural order.

In a new show, “Lush Interiors,” at the Memphis Botanic Garden, Breeden expands his practice into three dimensions: The collages are separated out on several wooden planes, which, in turn, are bolted together to create a layered image. Breeden makes the cuts using a CNC router, and so, like everything else on the Elevator Ride, the panels are cleanly designed. This approach is a step forward but not a departure from the artist’s earlier work, which variously portrayed the crystallized and melting visage of Miley Cyrus and mid-century dinner parties gone psychedelically haywire.

Tending the Typing Pool by St. Francis Elevator Ride

The collages in “Lush Interiors” bring to mind Renaissance botanical drawings. The outsized fruits of the artist’s imagination, coupled with some engineering-style linework, give the impression of a Taxonomy of the Weird. Even the assumed name seems to confirm: St. Francis, old world patron of the natural, goes on an elevator ride, otherwise known as the No. 1 American experience. So it makes sense that there is a good mix of gross Americana and transcendent florals visible in the work.

Breeden is a great designer, and his work as St. Francis definitely walks a border between art and design. But I’d be curious to see what would happen if he abandoned his spic-and-span design sensibility and let in some mess. After all, a 1960s grandma on hallucinogens would probably not have the time to clean.

Contemporary blacksmithing is not so much a job as it is a vocation, like nunhood or being a Hollywood stuntman. The average American teenager doesn’t just stumble into a smithy on the way home from Anime club, and so the few current-day souls who choose to spend their life in a forge are special. In my experience (and I used to work at the Metal Museum, so I get to have an opinion), the field is populated with people who love doing things the hard way, appreciate nature, make bad puns, and are usually very sturdy.

Bear these traits in mind when you go see the blacksmith E.A. Chase’s exhibit of engineering sketches, on view at the museum through October 2nd. The small exhibit is located on the first floor of the museum’s library building, and, though it isn’t the flashiest show in the museum’s history, it is certainly one of the most candid. You can imagine Chase, a white-bearded, veteran craftsman, sitting in his California studio and carefully shading in his imaginative designs of steel mermaids, copper monkeys, and iron dragonflies.

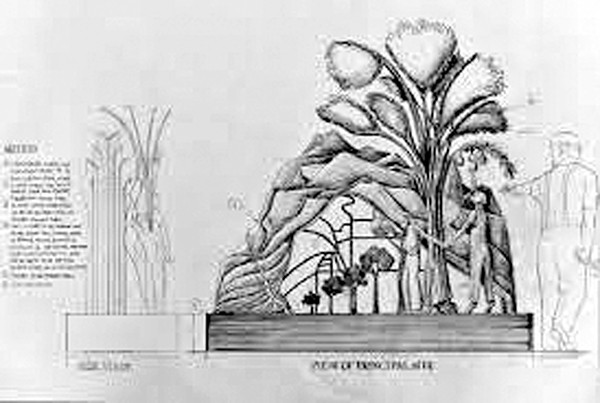

E.A. Chase’s Proposed Sculpture for the City of Exeter, California

Chase is one of the 20th century’s most noted blacksmiths, a New-York-educated craft revivalist whose designs are both innovatively engineered and unusually artful. The artist made his drawings of gates, lamps, railings, chandeliers, and fireplace sets for a seemingly whimsical and monied Californian clientele. His butterfly-shaped steel gates, lovingly sketched on velum paper, will make you want to acquire coastal property and grow citrus fruit. Hand-serifed letters and accompanying sketches of miniature blacksmiths only add to the candor and charm of the work.

The show of Chase’s drawings offers visitors a chance to visualize the labor and extensive planning that goes into large-scale metalworking projects, even those that never came to fore. There’s something sad and beautiful about the drawings for projects that were left somewhere in the balance. One structure, a proposed public commission, showcases the complete history of the city of Santa Cruz from indigenous history to tech economy. The drawing is elaborately made, but the gate never came to fruition. A brief note beneath the piece reads that it “floundered in politics.”