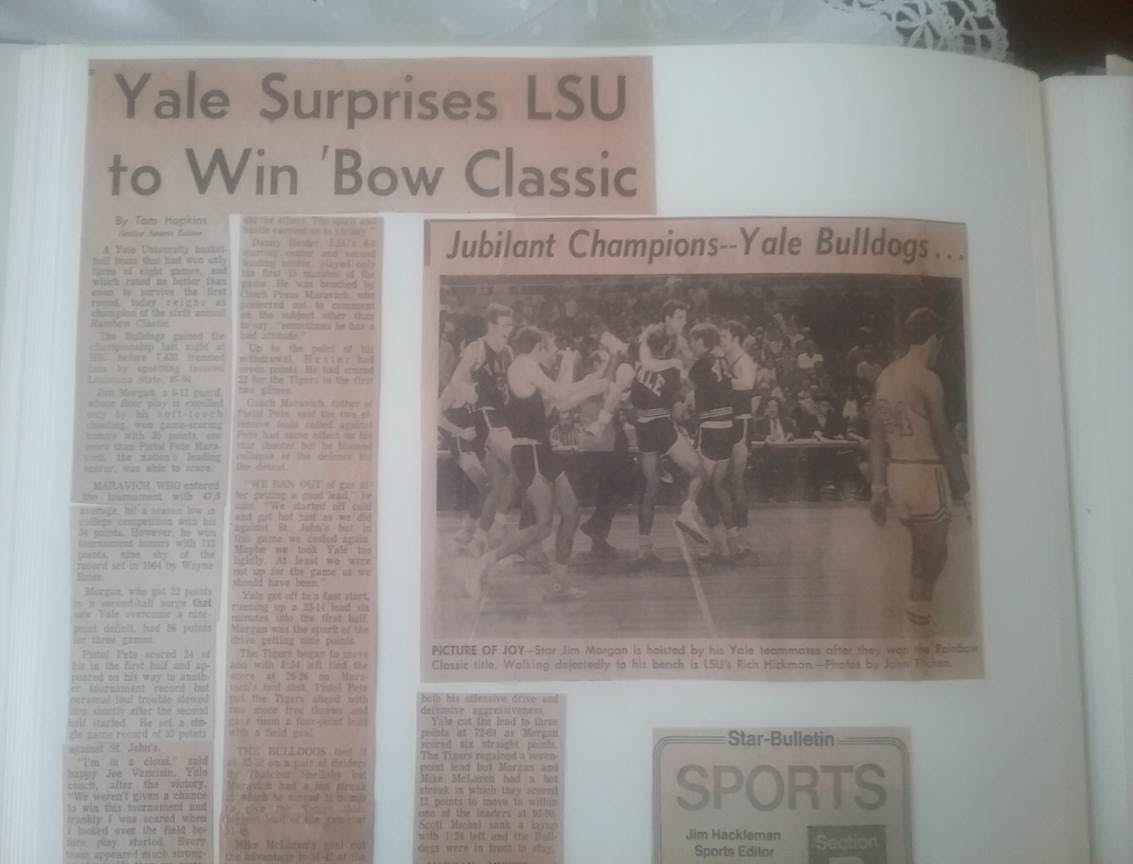

When the Ivy League-champion Yale Bulldogs tip off against LSU Thursday in the opening round of the NCAA tournament, the game will be merely one of 16 that day for millions of Americans highlighting their winning picks in this year’s bracket. But for one Memphian — attorney Mike McLaren — the game will serve as a happy reminder of a previous matchup between the schools, the 50th anniversary of that clash coming later this year.

On December 30th, 1969, in the championship of the Rainbow Classic in Honolulu, Yale upset LSU and its legendary guard, Pete Maravich. A player renowned for his wizardry as both a passer and shooter, Maravich had been named first-team All-America by the AP after both his sophomore and junior seasons. His Tigers were 7-2 entering the Tuesday night game and heavily favored against the 5-5 Bulldogs.

On the floor that day for Yale was McLaren, a sophomore guard enjoying his first season in a varsity uniform. (Freshmen were not eligible then.) “Pistol Pete” entered the game averaging 47 points per game, but was held to 34 by Yale, one less than Bulldog guard Jim Morgan put up in the 97-94 shocker. (Maravich had scored 53 against St. John’s in the semifinals and would average 44.5 points for his senior season.)

“There are pictures where you’ll see four of us who are supposed to be guarding Pistol,” says McLaren, a partner with the Memphis law firm Black McLaren Jones Ryland & Griffee. “You’ve never seen better form on a jump shooter. He was 6’5″. I don’t know why I was expected to guard him.” [McLaren surrendered five inches to Maravich.]

Yale knocked off host Hawaii and San Francisco to earn a shot at basketball’s Beatle, his sagging gray socks part of an already growing legend. McLaren and his teammates knew they were sharing an island with a rock star on their flight west. Upon actually taking the floor to play him, the Bulldogs found something collectively that they didn’t know they had.

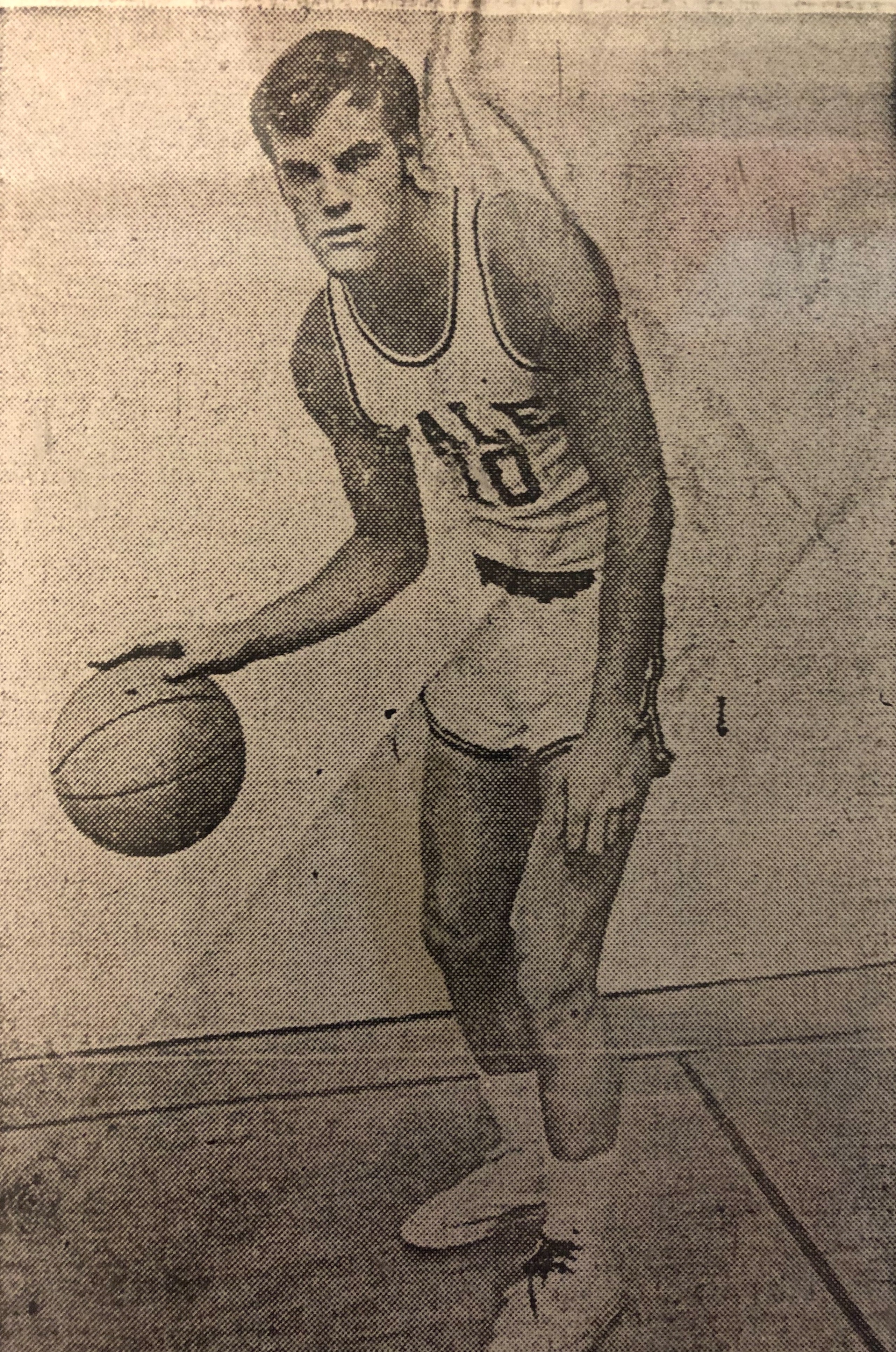

Mike McLaren

“Before the game in the locker room,” recalls McLaren, “[coach Joe Vancisin] said, ‘Mike, you pick up Maravich when he crosses half court. He’s got unbelievable range. When he beats you (it wasn’t if he beats you), Jimmy [Morgan], you switch over and help Mike. When he gets by Jimmy and Mike, John [Whiston], you gotta come out [of the paint] and pick him up. And Jack [Langer], you help Whiston.’

“Our forward, Scottie Michel, said, ‘Okay. I guess I got the other four.'”

How exactly did McLaren guard an unguardable player? “You had to force him left,” he says. “He almost never posted up. He brought the ball up court. We tried to get the ball out of his hands, into another guard’s hands, Rich Hickman. [Hickman] shot something like three for 15, so our strategy worked to that extent. If Maravich got within 15 feet, he just rose up and shot. They came down once, three-on-one, and I was setting up to take a charge [against Maravich]. He stopped on a dime, bounced the ball off the side of my head — on purpose — to a cutter. He was so fancy; it was impossible.”

McLaren played a supporting role to Morgan offensively, but scored 14 points, most of them over the game’s final 10 minutes. Maravich guarded him but, saddled with four fouls, didn’t want to risk disqualification as McLaren launched one midrange jumper after another.

“There was no defense at all by Pete,” says McLaren. “I remember partying hard after the game. I told the guys this was the high point of our athletic careers. We weren’t going pro.”

In Pistol, his 2008 biography of Maravich, author Mike Kriegel wrote that a “sunburned and hungover” LSU team lost to Yale in the game remembered so fondly by Bulldog players today. McLaren has an alternative view: “We were on the beach a lot more than they were, because we didn’t think we had a chance!”