Surely everybody in Memphis (and in the world at large, for that matter) is acquainted with the fact that a tragedy was visited on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — and mankind — upon the civil rights icon’s appearances in town in March and April 1968 for a dual purpose: to lend his unrivaled moral authority to the cause of striking sanitation workers and to gird for what was then an imminent Poor People’s March to be held in Washington, D.C.

The purposes were interrelated; Dr. King was on the brink of a subtle but huge change of course — from his familiar role of campaigner for racial equity to that of crusader for economic and political justice at large. The new mission encompassed the old one and had always been implicit in what King, already a Nobel laureate, thought and did. Some commentators have subsequently seen the Memphis sojourn as an ill-fated interruption of his life’s work. But the evidence is that he himself saw it as a previously unforeseen serendipity, as an opportunity to kindle the embers of the all-inclusive social revolution he had in mind.

In any case, King was no stranger to Memphis. In several previous visits over the years, he had foreshadowed his larger purpose. Though he may have passed through town on other occasions — Memphis is, after all, a crossroads city of sorts — his presence was particularly public and notable on four earlier dates.

July 31, 1959: King was already a celebrated personage of sorts when, at the age of 30, he came to Memphis to speak at the venerable Mason Temple at a Freedom Rally, called to support what was an unprecedented effort by Memphis blacks to mount a significant political presence in a local election.

Four African Americans were making a bid for public office in that year’s city election. The candidates and the offices they sought were: Russell Sugarmon, Public Works commissioner; the Rev. Benjamin Hooks, Juvenile Court judge; Elihue Stanback, tax assessor; the Revs. Roy Love and Henry Buntin, running for the Memphis School Board. They constituted what was being called the Volunteer Ticket, which also had one white member, Ray Churchill, who was running to depose Judge Beverly Boushe, referred to at the rally by the celebrated Rev. W.H. Brewster as “our longtime enemy.”

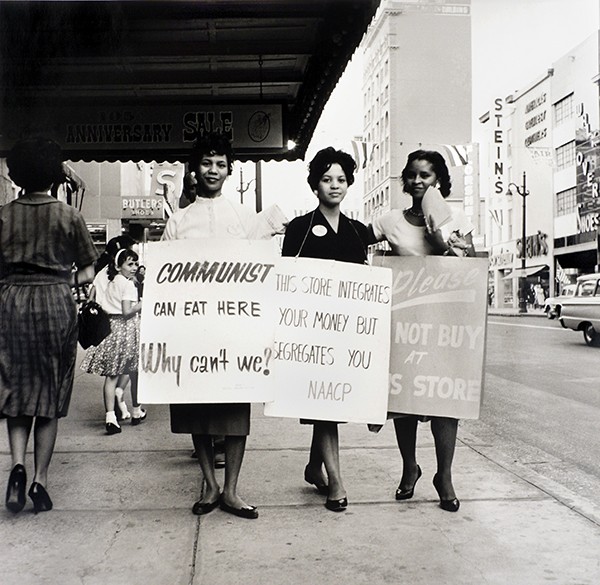

Gelatin silver print, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art purchase; funds provided by Sara and Kevin Adams, Deupree Family Foundation, Henry and Lynne Turley, Kaywin Feldman and Jim Lutz, and Marina Pacini and David McCarthy 2006.31.135 © Withers Family Trust

Other black eminences besides King were on hand to support the ticket — Daisy Bates of Little Rock’s desegregation battle; opera singer Mahalia Jackson, and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. But King was the cynosure. The Commercial Appeal headlined its morning-after report “‘Want to be Free’ is Chant At Big Negro Political Rally,” and began the lede, “Rev. Martin Luther King of Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott frame, inspired it and the audience echoed it.”

In a speech repeatedly interrupted by the aforementioned chant, King, who had taken up Rosa Parks’ cause and led a successful months-long boycott of the Montgomery bus system to end its system of segregated seating areas, told the crowd about the Montgomery participants: “They saw that ultimately it is more honorable to work in dignity than to ride in humiliation. They chose tired feet over tired souls.”

The rally also featured remarks by Lieutenant George W. Lee, a symbol of the black community’s Old Guard, who responded to King by saying, “We’re going to fight till hell freezes over, and, if necessary, skate across on ice in order to keep freedom moving in the right direction,” and by Sugarmon, who commented, “Many people still think of Memphis as Mr. Crump’s town and us as Mr. Crump’s Negroes. That ain’t so now.”

April 30, 1963: King was back in Memphis four years later for a local organizational meeting of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference and took part in another rally, this one hosted by Metropolitan Baptist Church and devoted to the subject of voting rights. Hooks, once more a candidate for Juvenile Court judge, and the Rev. Shuttlesworth were again on the bill, as were the Revs. Ralph Abernathy and Wyeth Walker of Atlanta, associates of King in SCLC.

But the turnout of just under 1,000 attendees — “spellbound,” they were called by the CA — was primarily, as before, motivated by a desire to see and hear King, who was only days away from playing the decisive role in Birmingham protests that would break the back of hard-core segregation in that industrial Alabama city.

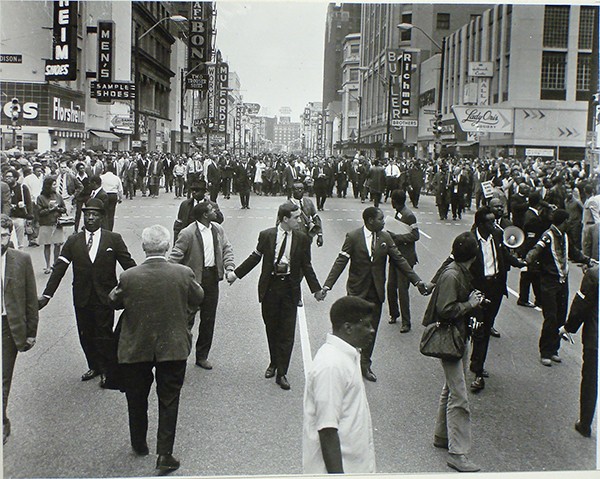

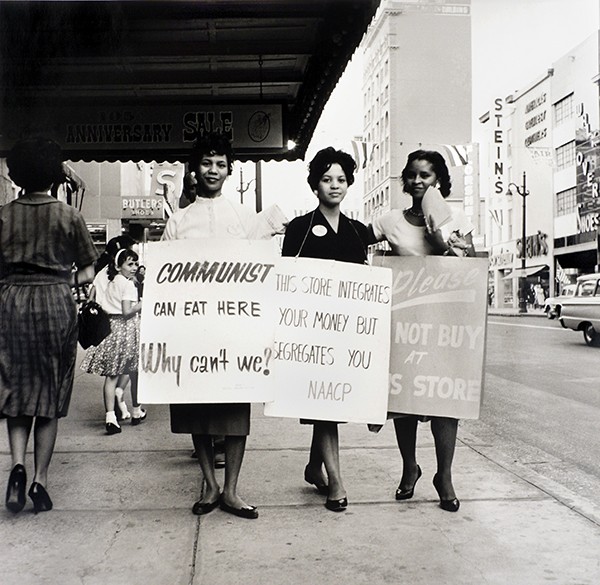

Gelatin silver print, printed from original negative in 1999, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art purchase with funds provided by Ernest and Dorothy Withers, Panopticon Gallery, Inc., Waltham, MA, Landon and Carol Butler, The Deupree Family Foundation, and The Turley Foundation 2005.3.116 © Withers Family Trust

The venue was once again Metropolitan Baptist, and local traffic was jammed for hours in advance of King’s appearance. The audience, forced to wait because of the snafu in the streets, sang choruses of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” during the delay.

Once Dr. King mounted the pulpit and got started, he was at his eloquent best, quoting from Shakespeare, Thoreau, Emerson, and even Sigmund Freud. “We are on the way to freedom land,” he said, emphasizing anew the importance of the ballot in the struggle for justice (“Even today, we can say to the Southerner, you may keep us from voting, but we’ll keep you from being president.”) and making a special appeal to children to join the burgeoning civil rights movement.

He bespoke his own impatience amid the gathering momentum of that year, which would include the March on Washington later in 1963, in saying, “I’m tired of seeing the first Negro to do this, the first Negro to do that. I want to see some seconds and thirds.”

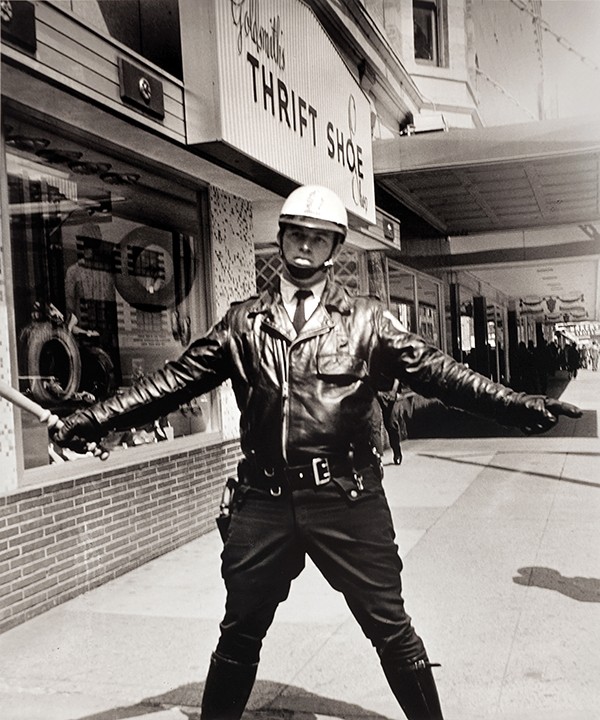

June 7, 1966: Dr. King’s next major visit to Memphis came as a stand-in of sorts for James Meredith, who had been the first black admitted to the University of Mississippi in 1963, amid rioting and even armed resistance on the part of white resisters. In early June, Meredith had launched a solitary March Against Fear, which began in Memphis and was intended to take him all the way to Jackson, Mississippi, the Magnolia state’s capital.

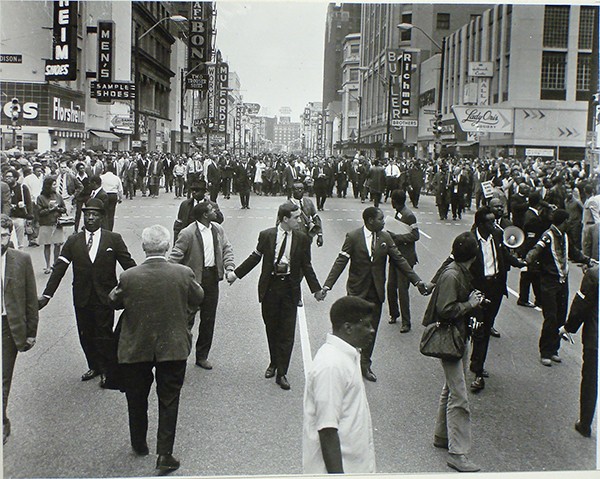

But Meredith was shot by a sniper just outside Hernando and hospitalized. King, along with 21 other marchers, hastened to the site where the march was interrupted and vowed to continue Meredith’s route to Jackson. Three Mississippi Highway Patrolmen interrupted the surrogate march and engaged in a shoving match with King, ordering him and the marchers to remove themselves from the main pavement of Highway 51 and do their walking on the shoulder of the road.

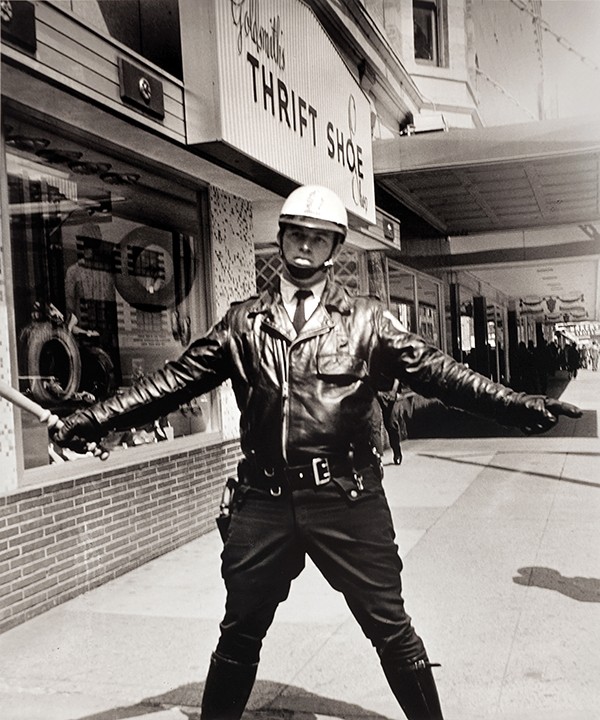

Gelatin silver print, printed from original negative in 1999, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art purchase with funds provided by Ernest and Dorothy Withers, Panopticon Gallery, Inc., Waltham, MA, Landon and Carol Butler, The Deupree Family Foundation, and The Turley Foundation 2005.3.35 © Withers Family Trust

“Why, in Selma we marched on the pavement,” Dr. King said, citing the previous year’s march he’d led that culminated in the passage of a voting rights bill in Washington. The head trooper replied, “But you had a permit then. We don’t care if you march to New Orleans, but get off the pavement.”

After taking an ice cream break at a local roadside stand, King and the marchers resolved to continue the march on the shoulder of Highway 51 and resumed their passage south. The numbers of marchers grew geometrically, day by day, including such other avatars as Stokely Carmichael, Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young, and, finally, by a convalescing James Meredith himself. Eventually a throng of several thousand, filling up the highway’s pavement, entered Jackson in triumph.

Commented King: “There is nothing more powerful to dramatize injustice like the tramp, tramp, tramp of marching feet.”

September 9, 1966: On that March Against Fear in June, Carmichael, one of the leaders of a new, more militant form of protest, had aroused much attention by a public call for Black Power. At the time, the advent of firebrands like Carmichael was widely seen as threatening the leadership of the civil rights movement by King and other apostles of non-violence.

On a return visit to Memphis and to Metropolitan Baptist Church for a meeting of the Progressive National Baptist Convention, King met the dilemma head-on. He gave a speech affirming his intent to hold his ground — and the movement’s. “If every Negro in America turned to violence tonight, I’ll still stand with non-violence,” he declared. “We will persist in the struggle against injustice, but we must use the proper methods in doing it. … Our power does not lie in Molotov cocktails and rocks and bottles. It lies in voting and the willingness to suffer for righteousness.”

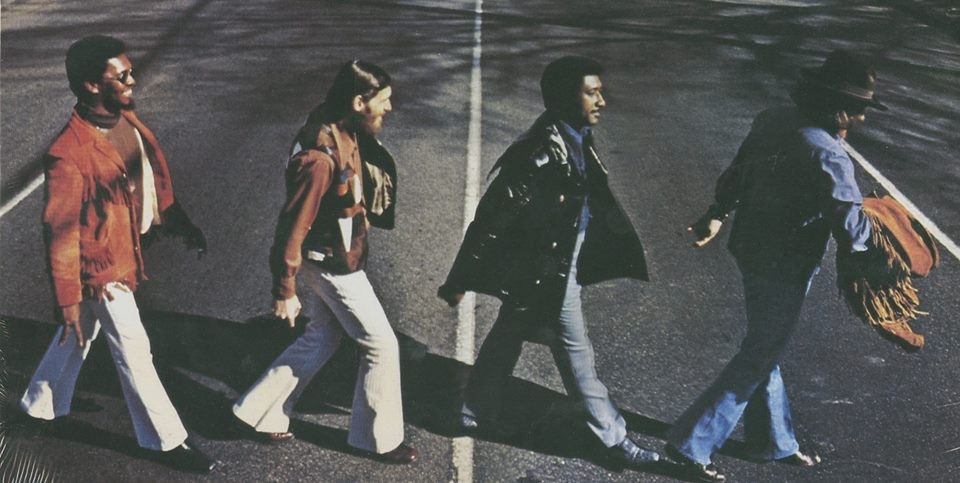

© Withers Family Trust

But, while his non-violent methods did not change, then or ever, King would become ever more militant thenceforth in his own way. In condemning the Black Power impulse as such, he had pointed out in that Memphis speech, “The weakness of riots is that they can be overcome by superior force, the National Guard. We need us something the National Guard can’t stop.”

But he, too, had shifted his emphasis. Speaking of an “invisible wall” barring the way to progress, he said, “The wall is perpetrated by white moderates who say to us, ‘Wait,’ by a federal government more interested in winning the war in Vietnam than in winning the war right here, by some white politicians, by some Negro politicians, by some white ministers, [and] some Negro ministers more interested in being Uncle Toms than in being just.”

Increasingly, for Dr. King, the task of “being just” had expanded beyond civil rights per se, beyond voting rights, and into the struggle to end the Vietnam War as well as into a new campaign to bridge the immemorial gap between rich and poor.

It was in pursuit of that latter dream that Martin Luther King conceived of the Poor People’s March and, as a warm-up of sorts for that mission, committed himself to assist the striking sanitation workers of Memphis in 1968.

Beginning with a visit to Memphis on March 18th, when he addressed the strikers and proclaimed solidarity with them, he would come back two more times, on March 28th for a march that would misfire, eluding King’s control and ending in violence, and one more fateful time, on April 3rd, with the intention of leading another march in support of the strikers and keeping it non-violent.

That night, though feeling ill, he would respond to entreaties from his associates and leave his room at the Lorraine Motel in the middle of a rainstorm, coming to Mason Temple, where he delivered his last rousing message in the powerful, climactic and unconsciously prophetic “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech.

On April 4th, on what would be his final occasion in Memphis, Dr. King was standing on the balcony of the Lorraine, preparing for an evening out with friends and supporters, when a sniper’s shot rang out, ending a gallant, courageous life and curtailing his final ambition — to accomplish the age-old vision of true economic justice — a vision that continues to this day.

MLK50 Events

Pinwheels for Peace

Events, ideally, should be fun or at least entertaining. But how to peg it around something that involves racism and a murder? Will it be too sad or scary? Is there an age limit for this sort of thing?

“Nobody’s too young for social justice or activism,” says Dory Lerner of the National Civil Rights Museum.

The idea, she says, is to turn it around into something productive. MLK50 Pinwheels for Peace is an example of that and is part of the larger MLK50 Curriculum called Creating Change through Action, which is geared toward parents, teachers, and activists and includes units on peace, justice, housing, education, poverty, and better jobs.

Kids all across the country at schools, nature centers, and botanic gardens are invited to make pinwheels and then plant them in a peace garden. Folks at the National Civil Rights Museum will be setting up a pinwheel-making station at the museum on April 4th, 9 a.m.-3 p.m. Participants are asked to reflect on what they can do to make the community better while making the pinwheels. Pinwheels for Peace runs through April 9th, the day of King’s burial.

“Our goal is to fight,” says Lerner, “but instead of using our fists, we use our minds, our voices, our feet.”

— Susan Ellis

Other Events

Seeing Civil Rights Symposium

Brooks Museum, March 28th-29th

Exploring Ernest Withers’ photography as art and a political tool. Features a keynote speech by Teju Cole.

The Mountaintop

Halloran Centre, March 28th-April 1st

Katori Hall’s drama about King’s last night.

At the River I Stand

Halloran Centre, March 31st, 3 p.m.

Screening of this documentary followed by a panel talk hosted by former NAACP president Cornell Brooks.

Final Footsteps of Martin Luther King Jr.

Tennessee Welcome Center, April 3rd, 9:30 a.m.

Tour retracing King’s last steps, including stops at Clayborn Temple, Mason Temple, the Lorraine Motel, St. Joseph’s Hospital, and R.S. Lewis Funeral Home. Features a keynote speech from Eric Williams, curator of religion at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

Memphis 50 Years Later, Marching Forward

Mike Rose Theatre, University of Memphis, April 3rd

Part of the Where Do We Go From Here? Symposium with panels on education and poverty and a talk by historian Taylor Branch.

IRIS Orchestra “It’s Up to Us”

Clayborn Temple, April 3rd

Program based on a speech by King with commentary from Dr. Harold Middlebrook.

I Am 2018

Mason Temple (930 Mason), April 3rd

Commemorating King’s Mountaintop speech. Featuring Danny Glover, Common, Andrew Young, Bernice King, and others.

Reenactment of “I AM A MAN” photo

Fourth and Beale, April 4th, 6 a.m.

A reenactment of iconic photo by Ernest Withers.

50th Anniversary Commemoration

National Civil Rights Museum, April 4th

A day full of events reflecting on this horrible anniversary, with tributes starting at 10 a.m, a 6:01 p.m. (the time of the assassination) bell toll, and an evening of storytelling starting at 6:15 p.m. at Crosstown Concourse.

For more events, go to mlk50.civilrightsmuseum.org.

Flynt | Dreamstime.com

Flynt | Dreamstime.com

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Kaitlyn Flint

Kaitlyn Flint

Button Brigade

Button Brigade  Laura Jean Hocking

Laura Jean Hocking