My mother died from cancer in the spring of 2023 at the age of 86. I was her only child, 55 and heartbroken. While she lived many years with chronic arthritis pain, my mother Earline Duncan was joyful, energetic, and always eager to share with others. I called her “Mama.” But she was more than that to me. Earline Duncan was my good friend.

December 25th will be my second Christmas without Mama. To avoid debilitating woe, I look grief in the face. Nobody will escape. Life is death, and loss is love’s inheritance. I hug my anguish tightly and let tears wash over me like a flood. When I cannot cry another drop, I am refreshed. Then I rise from the couch and clean my house.

Mama’s death wounded my soul. I own a scab that Mercurochrome cannot heal. However, in the time since her death, besides crying, cleaning house, and writing for the Memphis Flyer, I have discovered another way to recalibrate. I call on Mama’s circle of octogenarian friends, who traveled this life with her from childhood to womanhood, and finally to the elevation of elder. I ask her lifelong friends to share their personal memories of Mama.

Just like Earline Duncan, Dorothy Rozier, Claudette Lacey, Hollye Shotwell, and Verna Vaughn survived the humiliation of second-class citizenship in Jim Crow Memphis during the 1940s. They grew up and went to church in North Memphis’ Greenlaw Community. They graduated from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and they each served Memphis students as “Negro” schoolteachers until the vernacular changed to “Black” during the 1960s.

Once while I was collecting memories, Dorothy Rozier, who is 86, recalled my mother’s unmitigated boldness. When they were girls in middle school, Mama rode her bicycle to Dorothy’s house. At the time, Dorothy’s granddaddy sat on the porch in need of a shave because he was unable to do it himself. When little Earline arrived, she hopped off her bike and volunteered for the task. As a kid, my mother was given a straightedge razor. And according to Dorothy, “Earline shaved my grandaddy like she was a bona fide barber.”

Claudette Lacey and Hollye Shotwell are daughters of the late Lucille Martin Hinton. The sisters were frequent visitors in my mother’s childhood home on N. Third Street. Hollye is 84. Claudette is 88. As classmates, Claudette and Mama went to school together from first grade at Grant Elementary until they graduated from Manassas High in 1954. When I ask about Mama’s personality as a teenager, Hollye says, “Earline liked to read books and she loved to talk.”

When we speak on the phone, Claudette tells me, “Alice Faye! You sound just like Earline.” It pleases me very much that some audible part of my mother resides with me.

As for Verna Vaughn’s friendship with Mama, their herstory intersected through girlhood, fellowship at St. James AME Church, and their employment in the Memphis schools. Mama was eight years older than Verna, who recently turned 80. As children, Verna and her sister Carol deemed Mama to be an “authority figure.” Verna says, “Earline was the big girl who walked the little children to Sunday School. She would fuss and make us behave in church.”

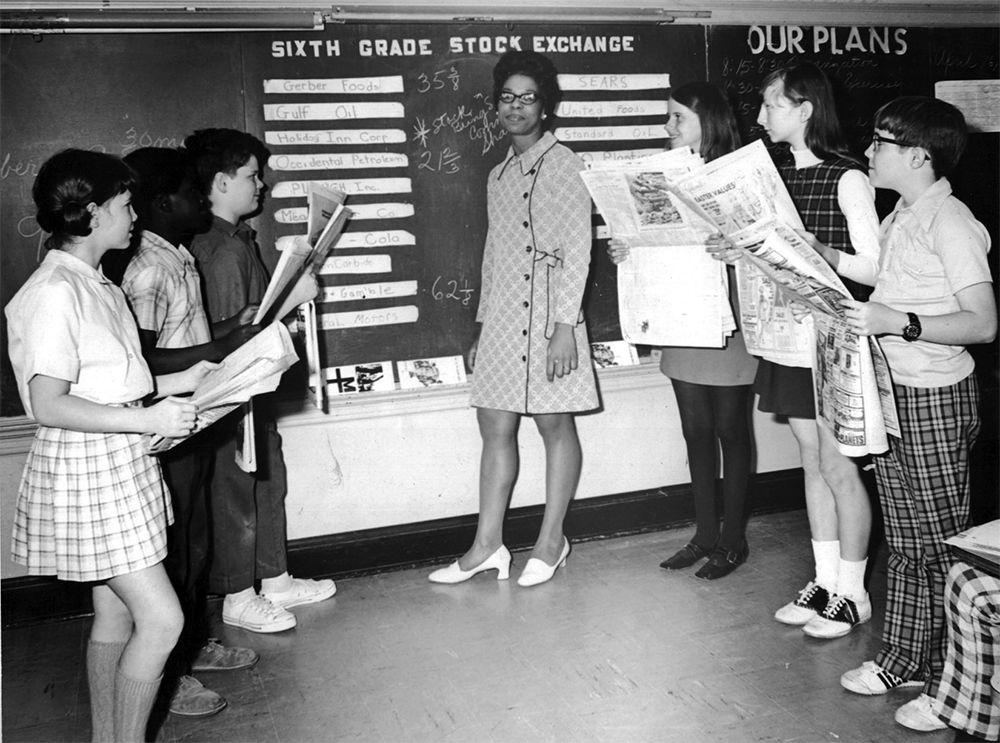

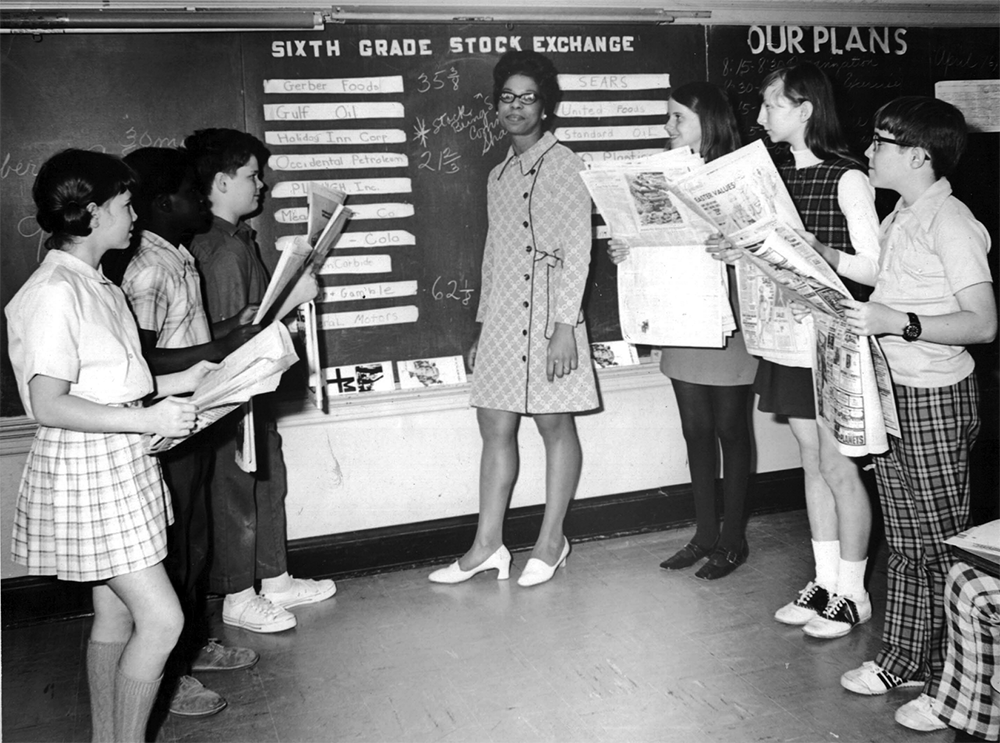

When segregation was abolished in the Memphis schools, Mama and Verna joined a cohort of Black teachers who integrated the faculty at Snowden School. Verna was the librarian and Mama taught 6th grade. As her coworker, Verna discovered that my mother’s intolerance for foolishness was unchanged. She tells me often, “I would walk to her classroom to chitchat and socialize. But Earline would stop me at the door and say, ‘No-no, Verna!’”

Do you miss somebody this holiday season? An old adage says that we live forever if people continue to speak our names. Therefore, gather with others and call to mind your special person. Giggle, gush, and luxuriate in the glow of who they were. Raise your voice and speak many names. Remember love. Happy holidays!

Earline Duncan served as a Memphis teacher for 39 years. To hear her speak about the integration experiment in local schools, visit Rhodes College at vimeo.com/279358197. Alice Faye Duncan is a Memphis educator who writes for children. Learn about her books at alicefayeduncan.com.