Plenty of history books magnify the mission of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was an American champion for the marginalized. While I celebrate his birth each January — and join in remembrance on the anniversary of his April assassination — allow me to shout from the rooftop that the historical impact of his wife, Coretta Scott King, goes largely uncelebrated. As a writer devoted to researching the Civil Rights Movement, I consider America’s lackluster regard for Coretta to be a crying shame.

Coretta’s legacy of social action and promotion of peace deserves to be widely extolled in books and the naming of schools and streets. Without her fortitude, it is likely Dr. King would not have reached his full stature as a civil rights leader. It is also likely that without Coretta’s tireless campaign to establish the King holiday, national and international deference to Martin’s name would be less prominent and shining. If this sounds like an exaggerated assertion, think again.

In 1956 when Dr. King denounced segregation and was a voice for nonviolent protests during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, white segregationists bombed the parsonage where the Kings lived with their firstborn child, Yolanda. While Martin was leading an evening strategy meeting, Coretta and their 10-week-old baby were home when the explosion blasted the front porch to pieces and blew a hole in the living room wall.

No one was injured, but the explosion was a sure reason for Coretta to quit the protest and leave Montgomery for safety. Coretta’s parents, Obadiah and Bernice Scott, lived in Heiberger, Alabama, 80 miles west of Montgomery. Mr. Scott drove to the parsonage expecting to carry his daughter away from danger. Coretta told him, “I am going to stay here with Martin.”

Montgomery was not Coretta’s first encounter with racial terror. When she was a teenager, segregationists set the Scotts’ house on fire. Mr. Scott raised pine timber on the family’s 300 acres. It was the mob’s intention to break his entrepreneurial spirit, but smoldering embers did not make him flinch. He built a new home. Years later, he purchased a lumber mill and segregationists also burned it to ashes.

With faith in a power greater than himself, Coretta’s father stood steadfast in Heiberger to, finally, open a thriving grocery store that served all citizens in Perry County. Just like the song, Obadiah Scott wouldn’t let “nobody” turn him around. He was Coretta’s model of courage. And during the Montgomery bombing, Coretta followed his example. Like her father, she stood unflinching in the face of fire. Coretta then went on to march beside Martin during the Civil Rights Movement from its early days in 1956, until her husband’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

Imagine the outcome if Coretta had abandoned Martin and the movement in Montgomery. If she had fainted in the face of fire, would anyone blame Martin for leaving Montgomery to save his marriage? Absolutely not. But the inward call to pursue freedom in Jim Crow America also weighed heavily in Coretta’s soul. Therefore, Martin never had to choose his family over the movement. And privately, when Martin wanted Coretta to adjourn movement work and be content with motherhood, she reminded him, “I have a call on my life, too.”

During their 13 years marching in the name of civil rights, Martin suffered violence, death threats, and constant trumped-up jail charges. It was Coretta’s disdain for tears, her unwavering words of encouragement, and midnight prayers that helped her husband stay the course. Martin called her “Corrie,” his “brave soldier.”

Few Americans understand the impact of Coretta’s warrior spirit because history books do not adequately explore her life as an activist, leader, and prophetic voice of liberation. Magazines from the ’60s overlooked the bravery in Martin’s warrior woman. Photojournalists rendered her portrait in elegant, unchallenging tones. And from patriarchal pulpits after Dr. King’s murder in Memphis, Black preachers encouraged Coretta to stay pretty and silent, while they jockeyed for positions that once belonged to Martin.

Black male leaders of the movement did not grasp that Coretta was the seed of Obadiah Scott. Burnished by fire, she was incapable of reducing her light. Coretta Scott King followed her own mind. And after Martin’s death, for the next 15 years, she used her voice to promote principles of nonviolence as she rallied the nation to establish a federal holiday to honor Dr. King, a drum major for peace.

As for Martin, Coretta, and the mystery of love, some people believe that marriage is a divine union where two hearts become “one flesh.” If that is true, let me propose a new tradition. Whenever you remember and celebrate the name of Dr. King for his efforts in human rights, be sure to praise and amplify that fated love, who wielded courage to walk as one with him. Her name was Coretta Scott King. She was born April 27, 1927. Martin called her, “Corrie.” She was a woman, wife, and warrior on the battlefield for freedom.

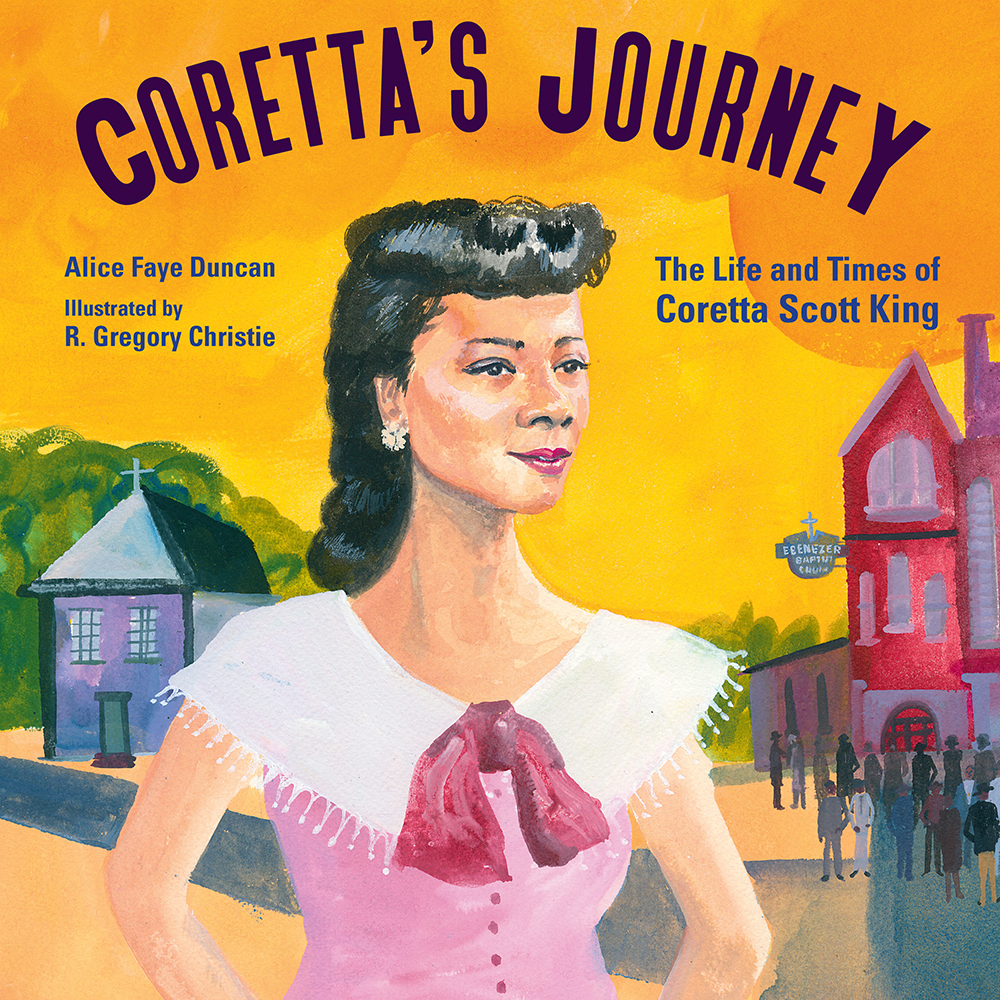

Alice Faye Duncan is a Memphis educator and the author of Coretta’s Journey; Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop; and Yellow Dog Blues, a NYT/NPL Best Illustrated Book selection in 2022. Visit her at alicefayeduncan.com.

*This piece was originally printed in the Dallas Morning News.