In a decade, Megan Abbott went from publishing her dissertation about “the solitary white man moving through the city” in mid-20th-century American hard boiled fiction (book title: The Street Was Mine, 2002) to subverting classic period noir settings with women-character-driven stories in Edgar Award-winning fashion (Die a Little, 2005; The Song is You, 2007; Queenpin, 2007; Bury Me Deep, 2009) to contemporizing noir themes in teenage settings, coming of age as criminal loss of innocence (The End of Everything, 2011; Dare Me, 2012). That last one — a cheer noir with an ostensible villain cheerleader every bit as dangerous as the head of a fictional crime syndicate — put Abbott further into the cultural conscious than ever before. The book has been optioned for a film with Natalie Portman attached to star (though it may end up hitting the screens as a TV series).

In the fall 2013 and spring 2014, Abbott served as the John and Renée Grisham Writer-in-Residence at Ole Miss. There, she taught MFA and undergrad writing classes and worked on her next novel. She also participated in the SRO Noir at the Bar event at Proud Larry’s in February, along with notable local writers Ace Atkins, Tom Franklin, Jack Pendarvis, and William Boyle. That night, she read from her new novel, The Fever, based on real happenings a few years ago in Le Roy, New York. Eighteen high school girls developed vocal and motor tics. There were theories about what was causing it — environmental toxins, fracking, the HPV vaccine, or simply a case of “mass hysteria.” Abbott began writing her fictionalized version the day she heard about the incidents. “It was like I had been waiting to write a story about that kind of case, and then that kind of case happened,” she says. It’s the book that appears to be about to permanently ensconce Abbott on the Rand McNally of the publishing world.

The Memphis Flyer sat down on a May afternoon with Abbott at the literary seat of power in Oxford, Square Books. Earlier that day, she had finished teaching her last class, and within a week she would be heading back to her home in New York.

Memphis Flyer: How was teaching at Ole Miss?

Megan Abbott: Their writing is exemplary here. It’s a really vigorous [creative writing] program. They’re committed, they believe in writing, and they take it seriously.

Did you learn anything about your own writing teaching others to write?

I couldn’t have articulated before about how important it is to make weird choices in your writing. When you make a weird choice, you’re drawing a line with the reader, and when you get the reader across that line, you have them forever — or for the book at least. Because you’re asking them to think about or ponder or feel something they didn’t think they were going to have to feel. It’s the theme of all the books I loved as a kid, and it’s still how I value [a] story. Though it isn’t the content that has to be weird, sometimes it’s the sentence structure or language.

I read a lot of spooky stories and a lot of true crime as a kid. You remember Archie comic books? I used to love them. They have a very glorified view of America and teenager-dom. But I bought an issue once that had a Betty plotline. She looks in the mirror one day and has red blotches on her cheeks, and she can’t explain it. She’s horrified. It turns out to be some kind of familial curse, and there’s a vampire in it, and a ghost, and a gypsy … . What was happening was, the publisher was experimenting with doing an Archie version of Dark Shadows. But it blew my mind because it’s not what you expect when you read Archie. And because of that, my mom gave me Jane Eyre to read. So it turned me on to these Gothic books.

What do you think of them killing off Archie in the July issue?

I know someone who’s a publicist for them, the crime writer Alex Segura. He told me about it in advance. We were talking about how it would be great to have a noir Archie, and he said, “Wait until you see what’s gonna happen.” But, I have a feeling the reports of his death are greatly exaggerated.

Did you read the Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips Criminal storyline [The Last of the Innocent] that has the Archie take-off in it?

Yes. In fact I know Ed now, but I didn’t when I read it. I’ve written for some of the back pages in Criminal, because he has a similar idea about breaking the thing that looks perfect; it’s sort of the Twin Peaks thing. It opens up to this dark matter inside.

You’re from Michigan?

Right outside of Detroit in Grosse Pointe. But the town has an unbelievably stark dividing line. There’s one street where it turns from Detroit to Grosse Pointe, and nothing passes between them. All the perils and troubles of Detroit never seem to touch Grosse Point, which will be 1954 forever. I didn’t grow up in the affluent side of Grosse Point — I lived near the freeway. That’s how we used to divide it, if you lived by Lake St. Clair or if you lived by the freeway, and how many digits you had in your address. The fewer digits you had, you were closer to the lake. It’s where all the auto magnates built these big houses. It has a yacht club and a hunt club. It’s always had that reputation of being old money and hasn’t changed that much.

Is the community in The End of Everything that same kind of suburban place as Grosse Pointe?

In my head it is, though not as wealthy and class isn’t so much an issue. Visually, that’s what I was picturing. There is a lake there, and you can’t go in it. I had references to that in The End of Everything, and [when the book was in production] there was a fact-checking question about lakes not having currents. I was like, wow, you don’t know the Great Lakes.

What about in The Fever. The same kind of place?

It’s more of a small town. I was thinking of it like a Nathaniel Hawthorne story, with a really contained place. A panic has a bigger effect there.

You had a normal upbringing, nothing too crazy?

It was alarmingly uncomplicated. [Laughs.] It was a book-loving household. My dad is a professor at Wayne State and a writer. My mom wrote on the side and now writes short stories. My brother is a compulsive reader. We passed around books constantly. That made its mark on me more than anything specifically in my childhood.

Were you allowed to read anything you wanted?

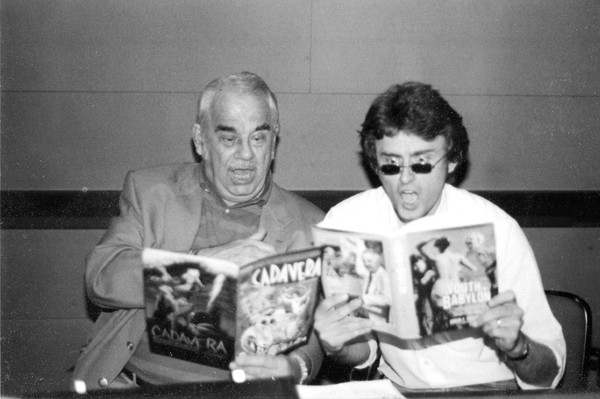

Yes. We used to go to used bookstores a lot. Because of the dramatic quality of the covers, I was drawn to true crime at an unhealthy age — not that it really had an unhealthy effect, because it didn’t do anything to me. But the books terrified me, and you love to be scared as a kid. I remember reading at an early age Helter Skelter and Hollywood Babylon. I liked looking at the pictures in the middle of the book and reading all those tales of women who marry men who are con artists who then kill them. I read mysteries like Agatha Christie as a kid, but I didn’t discover crime fiction until high school.

Like the actual hard-boiled classics?

I was working my way through the canon, and I knew of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett from the movies, but I didn’t even read most of those until grad school. I picked hard-boiled fiction for the thesis so that I could read them.

There wasn’t a bigger reason than just that you wanted to read them?

I didn’t think they got enough attention. Once I read one or two, they were so great to me, and important and influential, that I couldn’t believe I hadn’t been taught them in a class before. And I had gone through countless English classes by then. They’re still not taught enough. And there’s no reason you couldn’t teach Hammett’s Red Harvest in an American Literature class. And it wouldn’t be another dissertation on William Faulkner — which I would’ve absolutely enjoyed, I partially came to Ole Miss because I love Faulkner. But I felt like it would be fresher terrain.

You went to the University of Michigan, and then to NYU for grad school?

I started out wanting to study psychology, and then film, and then, like many others, I landed in English, because you get to talk about books all the time. I wanted to move to New York with two of my girlfriends, so I applied to NYU for the master’s program to give me a reason to go there. I ended up getting my Ph.D., too, because I wanted to talk more about books!

When in all this did you begin to write?

I took a few workshops as an undergrad, and it wasn’t until I started working on my dissertation that I wanted to write something in noir town. I had read Joyce Carol Oates’ Blonde, which feels noir when you read it. I started writing about 50 pages of The End of Everything, but I had no idea how to write a novel. It became a crime novel when I discovered crime fiction. I had a situation but I didn’t know what the book was.

There seems to be a change between the classic noir settings of your novels up to Bury Me Deep and the more contemporary novels from The End of Everything on. Do your agent and publisher suggest that you try certain types of books?

I wanted to do something different for myself creatively [with The End of Everything]. I could write mid-century party scenes forever and never get tired of it. But I thought it would be harder to write closer to present day, because it didn’t feel glamorous to me. Once I started writing the book, I figured out how to make it interesting to me. It was good to take that risk. Somehow I could bring the themes of the earlier books into this world and they would take different shapes.

In the last three books, there’s a character who a little obsessively observes another family, or idolizes a friend or an older sibling. Is that kind of a glamour you’re talking about?

I meant more like an atmosphere or mood, but you’re more right because I do always have the character see something else in some enchanting way. And that’s the energy that pushes the book that they want in that world.

There’s a mystery to that idea, too, because there’s always something darker behind the door.

And ultimately the darkest person is usually the one looking. As a David Lynch fan, you know where that comes from. That always happens.

Kyle MacLachlan in the closet in Blue Velvet.

Exactly. Addie in Dare Me is in many ways my darkest character of all. Which was surprising. But, “It lurks in all of us,” right? The Fever is the only time I don’t exactly do that — they’re probably the nicest protagonists.

There’s a theme of compulsion running through your books: Characters are doing things that are bad for them, and they cannot help it, and they want to do it.

Definitely. That is, to me, the thing of everything. [Abbott laughs.] It’s the only thing I understand that drives a story. Unexpected compulsive behavior is like how all of the plots are propelled in my books, along with the idea that in the end we trap ourselves and then we can maybe save ourselves. What’s really interesting to me isn’t bringing the reader to a catastrophic place but having them identify with the character and have them go places they didn’t think they would go. And then coming out of it somehow.

Is there an element of addiction to it, even beyond compulsion? In Queenpin, the protagonist is in a relationship with a guy, and she knows her boss might kill her because of this, and it doesn’t matter, she cannot stop it. That’s an addiction; the thing you’re doing will probably kill you and it doesn’t matter.

Addiction absolutely applies, but I think how I framed it in my head was like in Double Indemnity, with Walter, and there’s a line in the book where he knows that Phyllis is bad, that he’s going to get caught, and he wants to peep over the edge and he can’t stop himself, which is compulsion. It’s not nihilism, but more a sense of one’s destiny. Which is why I’ll never leave the noir sensibility, because I do believe in that. These are people driven by the Freudian death drive: They don’t want to die, but they want to go to the edge. That’s what’s so funny in Queenpin, because it was weird to have a female character express that. Vicki Hendricks does that in Miami Purity. She does the plot of The Postman Always Rings Twice and switches the genders. In the case of Queenpin, it’s a power test with Gloria, too. She’s in many ways a practical person. It’s so weird thinking about it now. Because they just want it and they don’t necessarily want to stop and then they don’t want to stop and they don’t want to stop and they don’t want to stop. And the protagonist is young, too. Which is a reason I knew teenagers would be good to write about, because they don’t always think through the ramifications of their choices.

Your novels share the characteristic of a young woman character who encounters a new, dangerous world in a noir setting, and your more recent novels seem to literalize the idea within the context of the humid violence of coming of age.

Yeah, and you’re making yourself in some way, so it’s got to be painful, and everything matters so much. It’s funny to think of yourself at that age and why you felt certain ways about yourself so keenly. That’s a way to bring those noir themes but make it realistic. That is your world when you’re a teenager. You read that and you remember being that age.

Do you have a lot of teen readers?

Increasingly, especially after Dare Me. Based on the early responses of the YA bloggers, that will probably be true of The Fever. YA and adult fiction are merging in a strange way that wasn’t true in my day — in my day there wasn’t even a thing called YA. A lot of adults I know read YA, and a million teenagers read adult books. I’m not purposely trying to write a book so an adult and a teen could read it — I don’t know how to thread that needle — but I’m glad they can. I’m especially glad when teens don’t find my books condescending, especially young girls, who are often treated as objects or drama queens or a pop culture parody in some way. I’m sure there are cheerleaders who found that Dare Me isn’t like them, but some have told me that it is, and that it’s actually even more extreme. There are a lot of former cheerleaders at Ole Miss, as you can imagine, and I had a student in class who said her experience was just like Dare Me.

Speaking of Twitter, I know through your account [@MeganEAbbott] that when you were young you were fascinated by the Michael Rockefeller disappearance. And now the new book has come out about what happened [Carl Hoffman’s Savage Harvest].

Oh, yeah!

Do you think there’s something about being a kid and a fascination with the idea that the whole world is mysterious? I fixated on disappearances and weird things and the show In Search Of and Time-Life Books … .

We had the same childhood!

What is it about childhood that makes us respond to those things?

When you’re a kid you feel you’re not allowed into the adult world and that there are secrets being kept from you — and there are literal secrets being kept from you. I remember my parents would have parties and I would be upstairs and try to hear what they were talking about, and they were laughing and they were drunk and were telling bawdy stories, and I thought, I want to know what’s going on! What am I not being told? What is out there? And I think kids are natural investigators — that’s why there are so many kid detective stories and series, it’s about that pursuit: I need to know, I need to know! And if it’s spooky you need to know more.

When I watch those clips of In Search Of on YouTube, I get terrified. I don’t even know if I would want a child to watch it. It gave me nightmares. The Michael Rockefeller book is the scariest book I’ve ever read, but it couldn’t just be what’s in this book; it was summoning back to years of childhood and that there were headhunters and cannibals out there and they were looking for you.

Another one like that is the movie Picnic at Hanging Rock. Give me a sneak peak of the essay you wrote for the new Criterion Blu-ray edition [being released June 17th].

I knew the film as a kid, and I saw it again in college. Criterion asked me to write the essay maybe because of The End of Everything. But watching the movie again after writing The Fever, I realized the movie is about hysteria. I wondered how much it had affected me more than I knew. My essay is about how the movie works because of its famous unresolved ending. Whatever theory we’ve been developing in our head about the mystery in the movie, we’re stuck with it. We know that it’s ours, our mind produced that, whether the girls were raped and killed or they were eaten by cannibals or whatever theory we had: We have to own it. That’s why people got so mad about the ending. There was a story [director] Peter Weir told about a studio executive throwing a coffee cup at the screen during an early screening. And I didn’t even know [the film] was based on a book [by Joan Lindsay], but it’s really good. It’s very short, and when they published it, they chopped off the last chapter, because it explains the mystery. It’s very creepy, but the book is much better without it.

That’s what makes it so powerful, because you just don’t know. The girls were swallowed by the land.

And it has a ripple effect on everybody. When I was a kid I know I was told it was based on a real life case, even though it wasn’t at all. People still think it is.

With Picnic, there’s a connection between the natural world and how portentous it is for these young girls. When I was reading The Fever and the lake that figures into the plot so much, it reminded me of Hanging Rock in the film. Everything kept going back to the rock, and whether it was the cause of the mystery or not, it didn’t matter so much as its importance to these girls.

Exactly. That emerged entirely organically. In the real case The Fever is based on, there was no lake. Part of it came from me growing up by a mysterious lake. Once I started thinking of the lake, its creepiness grew in my head: the smells and the feel of it. That it would have all this small town legend associated with it. You couldn’t go into the water. I remember people drowning in Lake St. Clair. When you’re a kid, that stuff lives in your brain. I love the Salem Witch Trials, and in that case, there’s the idea that these girls felt guilty about this thing they had done in the woods. I realized I had unconsciously wanted to do a version of that, and in the case of The Fever, it becomes the lake. It happened organically, and it became creepier and creepier and I couldn’t let it go. Nature scares me a little, it really does! Maybe it’s living in New York too long. But that lake was the nature of it, and it felt like a death trap. It was beautiful, but deadly. [Abbott laughs.] Plus, it’s really fun to describe. I researched the algal bloom and became fascinated by it. It was glamorous to me, strange and exotic.

How difficult was The Fever to write?

It was one of the easiest. I knew the story really early on, but I wanted it to stay frightening and to keep multiple possibilities floating and keep the ending a surprise. The challenge was to convey the bigness of the event in this small place.

Was there anything like that community-wide fear when you were growing up?

There was a time when I was a kid there were a lot of missing kid cases getting attention because of the Adam Walsh case. There were a lot of school meetings about it. They had the parents put a sign in their windows that was a fluorescent orange letter E. I don’t know what it stood for, but it meant that it was a safe place, so if you thought someone was following you, you could go into that house. Even as a kid, it seemed insane, because if you wanted to kill a kid, wouldn’t you put the sign in your window? You wouldn’t even have to go look for them, they’d come to you!

Is there anything you’re taking from your time in Oxford that has really stood out that might make it into a book, or is it too soon to say?

Yeah, the landscape and the way it’s a magical place; Oxford at night, especially. It’s so beautiful and mysterious, and it’s so different from the North and the Midwest. It will be after I’ve been gone awhile and am reflecting on it, but some glimmer will come.

Do you know what the next book you write from scratch will be?

I have a list of six ideas, and I need to see which one takes. I’ve narrowed it down. I’ve had a lot of false starts with books. It happened with The End of Everything. There are a few I won’t ever go back to because they didn’t catch fire.

Does your next book [now in revision] have a name yet?

It’s called You Will Know Me. It’s about a family with a child prodigy. They’ve always struck me as interesting families because of the way the power works. And then there’s a crime, obviously. I will consider that my Oxford book. I was well into it before I came here, but in Oxford I really pushed through the second half of it.

Is there a certain era you’d like to write about?

I’d like to do something in the 1910s or early ’20s. It was a time of great hucksterism and con artists. And also, like with the Helen Spence case [depicted in Daughter of the White River by Denise White Parkinson], there were still a lot of parts of America that were local in a way where there’d be local justice and rules, and outsiders could be dangerous.

When did you begin to really feel success as a writer?

There are always moments where you feel different, and then you get knocked back down. [Abbott laughs.] It’s filled with failure, and petty indignities, and large indignities. I’ve had great luck and beyond lucky to work with Reagan Arthur, the rock-star editor everyone wanted to work with. She edited Kate Atkinson and George Pelecanos and many others. But in the end you’re stuck with the book, and stuck with the page, and it’s not working, and often you feel like it’s so easy for some writers, and some are struggling more than you. You know how on Mad Men, the agency is growing, then it gets smaller, and they lose Lucky Strike — that’s how publishing feels. You feel like you’re on top of the world, then they pull the rug out from under you.

You’re headed home to New York soon?

Yeah, but I’ll be back in Oxford quite a bit. I’m guest-curating an exhibit at the museum, I’m on a few MFA committees, and I have a lot of good friends here. I can’t quit this place.

Has the collegiality in Oxford been good?

Yeah. It’s a writers’ town, or a book lovers’ town. New York is many kinds of towns, but in terms of books it’s a publishing town, with the business aspect of it. In Oxford it seems it’s more about words, so it’s been like being in this big bubble bath for a year. You just talk about books all the time. Everyone has rich personal histories, people like to go out and talk until the wee hours.

Is it still a novelty that you’re a woman writing crime fiction?

I’ll admit, in many ways it works to my advantage. I stand out more. But it’s true of crime fiction and other genres: Books written by men are considered bigger and more meaningful and significant because they’re written by a man. And when they’re written by a woman, they’re thought of as domestic or about relationships. Tom Perrotta, whom I love, writes about families or domestic issues or suburbia, and his books are important. But there are a lot of women who write about domestic issues or suburbia, and they’re considered Women’s Fiction.

It’s a genre in and of itself.

What does Women’s Fiction mean? I know what men’s fiction is: everything. [Abbott laughs.] But, I’ve never had a male reader say, “You write okay for a woman!” It’s just still this ghost out in the culture at large, a cliché we can’t let go of.

Your love of Mad Men is well known to me. Are you liking the season?

Yes! Don’t you think it’s great? It’s almost too good, it’s breaking my heart. Oh god, I don’t know what I’m going to do when it’s over, though I think they’re smart to end it. You quit while it’s this good.

You often write about Pete Campbell after an episode.

I love Pete. He’s really complicated, and no one gives him credit for it. They’re not watching the show carefully. He’s far more advanced with social issues than anybody else in that world. He’s self-destructive in interesting ways — in that plotline where he had the affair with the Gilmore Girl [Alexis Bledel], she sees a depression in him, a deep emotional sadness he can’t see. He always surprises me. The actor [Vincent Kartheiser] is so unafraid of looking foolish or gross. Don is always so slick, even when he’s grimy he looks gorgeous. Pete will just go there, he’ll fall, get punched — Billy Wilder would have loved him. He would’ve made Pete the center of the show.

Give me 3 books, TV shows, and movies that are important to you.

Mad Men, Deadwood, and Twin Peaks for TV.

For movies it would be In a Lonely Place, Sunset Boulevard or one of many Wilder movies, and Mulholland Drive, which I get in many arguments with people about. Blue Velvet is the more perfect film, but Mulholland Drive is the more complex.

For books, The Sound and the Fury, Farewell, My Lovely would be my Chandler, and Wuthering Heights. I read it far too young, I skipped all the dialect, but it spoke to me, and every time I’ve read it since, it’s rewarded me more.

So, Chandler over Hammett?

Yeah, he’s more personal to me. Hammett is the deeper thinker and politically more in tune with me, the way he sees the world in some ways. But Marlowe is probably my favorite character ever. I’ve read those books a lot, and they still surprise me.

Do you feel like you’ll ever catch up on everything you want to read?

No, and isn’t that a great feeling? You’re worried you might have hit the bottom, and you realize there’s a bottom beneath the bottom. A false floor.

You wrote the screenplay for Dare Me? Is that progressing?

That was one of the harder experiences, adapting my own stuff. It’s still in play. There’s been TV interest in it, too. Which in part I think it might be more suited towards. TV’s where it at! [Abbott laughs.] People have been interested in it as a series, because you could build it out and keep switching the power, the ascent and descent, like a crime family show, or Game of Thrones, for that matter. It’s interesting, given how important TV has become to my creative mind recently. There are so many doors opening up, there are so many shows that are more specific than they used to be. You remember 15-20 years ago, I’d watch almost anything because there weren’t that many choices. And now you can find things that feel like they’re made for you.

Have you been pulled in that direction?

I’ve gotten offers, but you have to move out to L.A., and I don’t know how that would be. But I know a lot of writers who are doing it. The collaborative element interests me, writing in a group like that seems really fun.

The Fever (Little, Brown and Company) is released on June 17th. Abbott will be at Square Books in Oxford on June 24th at 4 p.m.

[Updated Thursday, June 12, 2014, 1:52 p.m. for grammar]

Paul Schiraldi

Paul Schiraldi

Dan Ball

Dan Ball  Robin Tucker

Robin Tucker

David Thompson

David Thompson  Charle Berlin

Charle Berlin  Eric Page

Eric Page