As Memphis prepares for a 4th of July weekend, members and guests of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP are still savoring some moments last weekend from the organization’s centennial anniversary luncheon — particularly from keynoters Melissa Harris-Perry, former MSNBC host and Wake Forest professor, and Harold Ford Jr., the onetime Memphis congressman who now works on Wall Street and keeps his hand in politically, also on MSNBC.

There were notable things happening before keynoters Harris-Perry and Ford took their star turns, of course. Local NAACP president Deidre Malone and MC Mearl Purvis kept things moving from the dais, and a series of local dignitaries, including Ford’s successor, current 9th District congressman Steve Cohen and Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland, had some trenchant things to say — Cohen about the perils of the Trump presidency, Strickland about the need to boost African Americans’ share of local business opportunities.

Arguably, though, the best crowd reaction early on was to remarks by longtime civil rights activist Jocelyn Wurzburg,  JB

JB

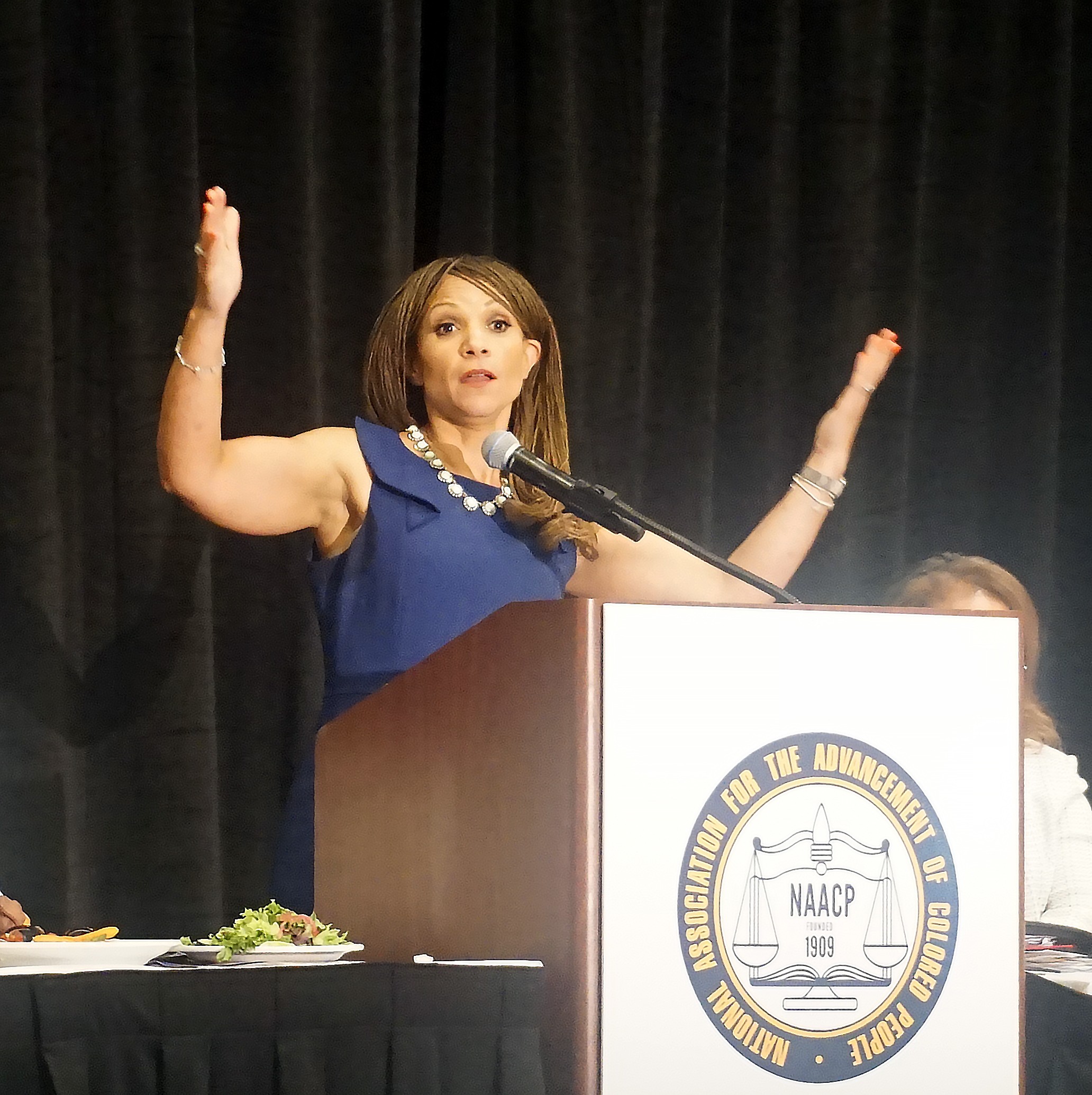

Melissa Harris-Perry

who (along with Shannon Brown and Roquita Coleman-Williams) was one of three official co-chairs for the event, held at the East Memphis Hilton last Saturday and devoted to the theme “Reflecting on the Past, Remaining Focused on the Future: 100 Years of Civil Rights and Human Rights Advocacy.”

Wurzburg, recipient of numerous citations and the person for whom Tennessee Human Rights Commission’s annual Civil Rights Legacy award was named, conflated two tales. The first was about being embarrassed in her early youth when her mother, without asking, signed her up as a member of the Daughters of the Confederacy; the second detailed her response, during a visit to New Orleans, when a resident of that city lamented Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s recent removal of Confederate memorials, including a statue of Robert E. Lee.

The New Orleans native insisted that Lee had been done an injustice, in that the Civil War, in which he led a Southern army, had not been done on behalf of slavery. Wurzburg countered that, “as a member of the Daughters of the Confederacy, I can assure you it was.”

Harris-Perry, utilizing her erstwhile media chops, would wow the NAACP audience with a deceptively stream-of-consciousness rendition, including flamboyant hand-and-arm gestures, of what was actually a tightly organized dramatic presentation, aptly illustrated by a series of slides.

And along with her mastery of the medium (two actually; that of television and that of the lecture hall) came several provocative messages. One was both powerful and original: Taking off from her declaration that America had elected a president who was both “a racist and a pussy-grabber,” she formulated a convincing argument that racial domination, in its various forms, had depended on a distinctly physical domination of black women.

Slavery, which had involved the calculated and merciless separation of children from their mothers, had continued “through us,” Harris-Perry declared. To maintain the current stratified social system, she suggested, “Black women have to give birth,” and thereby to yield up to others “not only the product of our labor but our labor….The people who run this joint are pussy-grabbers.” That, she said, was “the reality of our wombs.”

Noting the incidence of black domestic servants in her paternal ancestry visi-a-vis the fact that her mother’s side was white and relatively privileged, Harris-Perry identified strongly with the former and with the idea of building “from the bottom,” a moral that she said would apply both to the advancement of the NAACP and the redevelopment of a dilapidated Democratic Party. “You always have to start with the least of these, literally, Jesus said. If you start at the top, you will miss so much. If you start at the bottom, you will miss nothing.”

Harris-Perry was the proverbial Hard Act to Follow, but Ford, who came next and last, managed to do just fine.

Harold Ford Jr.

Professing that he was “glad to be home,” the former 9th District Congressman (who came within an ace of winning a Senate seat as a Democrat in 2006) executed an artful segue from Harris-Perry. Elaborating on the theme of “the power of women,” he recalled the importance of women teachers in his early education, extolled the helpful role played by “women in this district” in the development of his political career, and did some verbal doting on his 4 ½-year-old daughter Georgia.

Ford then shifted to the subject of change and to what he saw as a geometrically increasing demand for it in the society of today, treating the abrupt shift by American voters to Obama in 2008 and, even more precipitously, to Trump in 2016 as a case in point. The silver lining was the fact, as he saw it, that yet another political shift in a wholly different direction could happen, and relatively quickly.

“People want change, and they want it now,” he said, noting the pell-mell transformations of public technology, like the ever-escalating rise in photography via cell phone. He recalled being told two years ago that, within five years from that point, “97 percent of all the pictures in the world” would have been taken.

Ford closed on a note of optimism: “We’ve got to be daring and not afraid of change.” He quoted Babe Ruth to the effect that “Yesterday’s home runs do not win tomorrow’s ball games.”