It’s not the kind of remembrance people like to attach to those we historically have deemed as heroic martyrs.

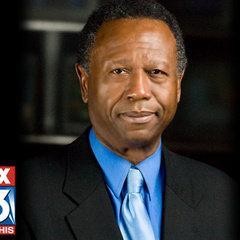

A man so disconsolate over what his critics and he himself viewed as abject failure, lying in a Memphis motel room bed, fully clothed, weeping and unable to move for 13 hours. Yet, in his book Death of a King, political commentator and talk-show host, Tavis Smiley, paints a sincere and honest picture of civil rights icon Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a man whose human frailties are put to the test in the final year of his life — in a struggle to regain lost prestige, popularity, and his own moral compass.

Beginning with his controversial Riverside Church speech in New York, delivered one year to the day before his assassination in Memphis, King attempted to lay out a new direction for the nonviolent movement he had fostered. With monumental civil rights legislation already on the books, King wanted to expand the scope and participation of the fight against what he saw as the interconnected triad of poverty, racism, and militarism that he felt was tearing away at the fabric of America during the height of the Vietnam War era.

It was an effort to expand on the coalition, which had proven so successful in winning the hearts and minds of those previously drawn to the civil rights movement. But, like others who’ve risen to great heights of leadership on oratory or sheer will, King unwittingly allowed himself to become more insulated from what was going on around him.

Smiley’s book deftly portrays King as a man on a treadmill. No matter how fast he tried to run, everything and everyone in his life was still passing him by, and he couldn’t understand why. He was the same. But, the rest the nation, which he once briefly held in the palm of his hand, had moved on in fractious directions, including his own previous inner circle at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

In Smiley’s book, one of King’s greatest disconnects was with women, and most importantly, his wife, the long-suffering Coretta Scott King. When they first met when both were in their early 20s, King openly admired her not just for her stunning beauty, but also because she became the most strident and unflinching supporter of his nonviolent strategy. Once they started having children, however, King encouraged her to be more subservient, while at the same time he continued his dalliances with other women. So, entrenched in his chauvinistic attitude, King initially rebuked his colleague James Bevel’s suggestion to all male members of the SCLC and other black ministers to tell their wives about their affairs with other women. According to Smiley, King finally did come clean with Mrs. King about one affair, which he told her he put an end to.

I also was drawn to the turbulent final month of King’s life, when it came to how the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike had become a cause celebre’ with him despite warnings from his SCLC inner circle, including apparently Jesse Jackson, that the issues in Memphis were “small potatoes” and not worth getting involved in. But, coming in a year in which he’d been booed off stages, and he was jeered and ridiculed as out of touch with his own people, the reception King received in coming to Memphis was reinvigorating. Memphis had become to him the potential springboard for his still not fleshed out idea of having a “Poor People’s March on Washington.” He viewed it as a golden opportunity to reestablish the nonviolent movement as a viable form of effective protest.

However, as he did through most of that tumultuous final year of his life, King miscalculated, believing the power of his persona alone could bring together divisive factions. The ensuing riot on Beale Street in March of 1968 devastated him enough to seek refuge in a room at the former Rivermont Hotel. King would regroup. His unwavering faith in his mission would allow him to do no less. But, days later, a bullet would be unforgiving.

I applaud Smiley for his determined and compassionate attempt to humanize a man so many authors before have either lionized or demonized. The book provides a lesson, a study in our own mortality. It encourages us to never be so self-assured, so defiant in the face of unwelcomed truth, or so tunnel-visioned about what we believe is right that we ignore the sage counsel of friends and neglect the love and support of family.

For all of us, even the greatest among us, are only mere mortals in the end.