Mars McKay is a Memphis-based, experimental horror filmmaker and the host of Black Lodge’s monthly LBGTv Queer Cinema Night. The avid cinephile had never seen David Lynch’s infamous 1984 adaptation of Dune. We attended a sold-out 40th anniversary screening of the film at Malco Paradiso, then retired to Houston’s bar for cocktails and debriefing. Coincidentally, while we were discussing Dune, we saw Memphis director Craig Brewer, who joined the conversation while he was waiting for his table.

Mars McKay: Hello, how you Dune?

Chris McCoy: What do you know about Dune, the David Lynch version from 1984?

MM: I have been trying to avoid everything at all costs! Well, I’m currently reading the book to prepare for Dune and Dune 2.

CM: How far along are you in the book?

MM: I am about halfway through, and according to my friends, I’m about where the first Villeneuve movie ends. The David Lynch, I hear, is very polarizing. When people start talking about it to me, I’m like, Uhuh, no. I want to go in with as unbiased and opinion as I can. So all I know is what I know from reading the book.

CM: What’s your attitude towards David Lynch?

MM: Oh, I love him. Love him. I’m not the biggest fan of Eraserhead, but Mulholland Drive! [makes chef’s kiss gesture] Which, I got my theories about … but I love his work.

137 minutes later …

CM: Okay, Mars. You are now a person who has seen David Lynch’s Dune. What did you think?

MM: I’m definitely smiling from air to ear right now.

CM: Yes, you are!

MM: My favorite character, the one I got the most hyped for, was Pug Atreides

CM: Yes! The Battle Pug!

MM: Battle Pug!

CM: We’re going to be out there shooting lasers at each other, so let’s take pugs into battle with us!

MM: Pugs can be ferocious!

CM: And it’s Patrick Stewart who carries the pug into battle!

MM: It was my favorite part of the movie — me and the guy sitting next to me with The Thing t-shirt. He and I were like, “Is that Captain Picard?”

CM: With hair!

MM: I, of course, was super on board with the presentation, the translation from the book to the movie, through the first half, up until the point where they start developing the relationship between Paul and Chani. After that, I was like, this feels rushed now. I loved it, though!

CM: It feels rushed because it is rushed. Here we are, about 90 minutes in, and we’re just now in the desert, meeting the Fremen, you know?

MM: In the book, that’s like 350 pages.

CM: Yeah. Because there’s all that world-building.

MM: Which I love.

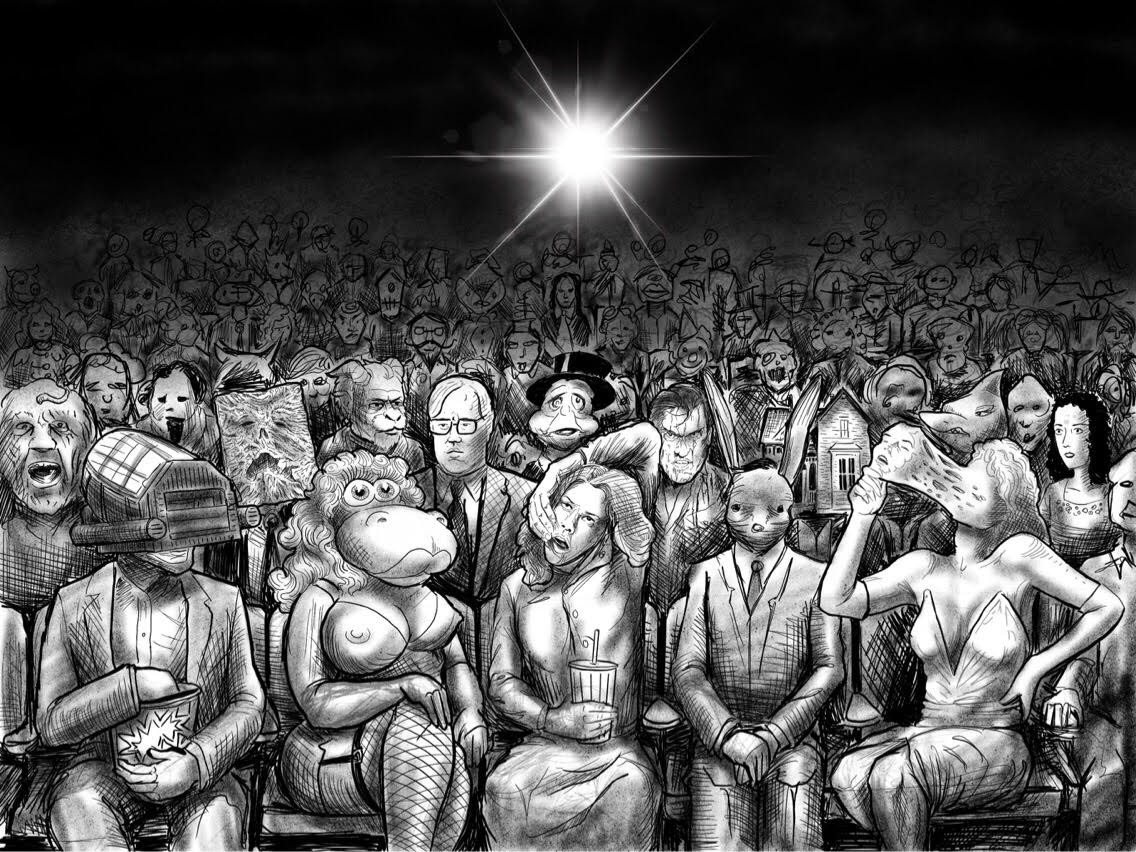

CM: Me too. But I think the real problem with adapting Dune is all the world building. At some point, you’re going to have to explain the thousand-year selective breeding program the Bene Gesserit witches were running to develop the ultimate psychic super-being, the Kwisatz Haderach, to a theater full of over-caffinated 12-year-olds. It’s a super complex narrative that doesn’t adapt easily.

MM: The white savior narrative, Paul as the messiah, is intentional. The Bene Gesserit went from planet to planet planting those myths.

CM: They did it on purpose.

MM: That’s something that was not addressed in the film at all. But it’s so ingrained in Fremen culture, their priesthoods connect. They already have their own Reverend Mother, and when she dies, Lady Jessica just steps in there and takes over.

CM: It was all a setup by the Bene Gesserit to create their chosen one …

MM: … and then the first thing the Chosen One does is turn on them.

CM: Right.

MM: He doesn’t want to do it.

CM: The real message of Dune is, “‘Don’t have Chosen Ones, they’ll always turn on you.”

MM: You could say it’s predetermined.

MM: One thing I really didn’t like about the movie was Paul’s sister, Alia the little kid. I haven’t gotten to that part of the book yet, but every scene she was in just made me a little uncomfortable. Like, just something about the way she’s shown.

MM: But overall, I really liked it. The first thing I said to you when it was over was, “I don’t understand why this gets so much hate.” But the last half does feel rushed, kinda cramped.

CM: I’m reading A Masterpiece in Disarray, which is a book about the making of Dune. Dino De Laurentiis produced it. He got David Lynch on board, and then said, “My daughter, Raffaella, you will produce it!” And she kinda didn’t know what she was doing.

MM: So, it was the financials. Speaking of David Lynch’s cameo …

CM: That was amazing! I’d never noticed that before!

MM: I didn’t realize it at first until you were like, “That’s David Lynch!”

CM: He’s the poor guy in the Spice Harvester going, “Hey guys, can you come get us before the worm eats us?”

MM: He’s got that voice.

CM: So Lynch, obviously, was not the right guy for the job, but I don’t know that there was a right guy for the job. There’s no way that you remotely do that story justice in two hours. It’s a long movie!

MM: It was two and a half hours.

CM: At one point it’s like, “For the next two years, there’s this giant war …” Well, that’s usually what we see in movies — stuff that’s important to the plot!

MM: I liked having Lynch as the director. It’s wild to see him do a space fantasy. I loved the dreamy elements within it, when Paul’s seeing the visions after ingesting spice. The visions are just fantastic.

CM: That’s David Lynch’s wheelhouse, you know? And there’s a lot of it in the book.

MM: They probably looked at that stuff and said, “Let’s get Lynch!”

CM: George Lucas tried to get Lynch to direct Return of the Jedi. Can you imagine?

MM: I don’t think that would have worked at all.

CM: After he was nominated for Best Director with The Elephant Man, he was a hot commodity around Hollywood for a while. He turned down Jedi because he wanted to do something that wasn’t an established vision, and did this instead.

MM: The Elephant Man is one of my favorites of his. People go from Eraserhead to Blue Velvet, and I’m like, “Don’t skip Elephant Man!”

CM: The psychedelia is impeccable. But what this story needed was a good editor, and I’m not talking about a good film editor, I’m talking about a good story editor. And that just wasn’t happening.

MM: That was my only qualm with it. The pacing at the end where it just felt kind of like doing a visual, as opposed to the way stretched out first half. I was super happy to see that ’cause I’m really loving the book. But seeing that presented and then all of a sudden, the moment the whole stuff with Chani happens, it just felt like it’s trying to squeeze into pants that are too tight.

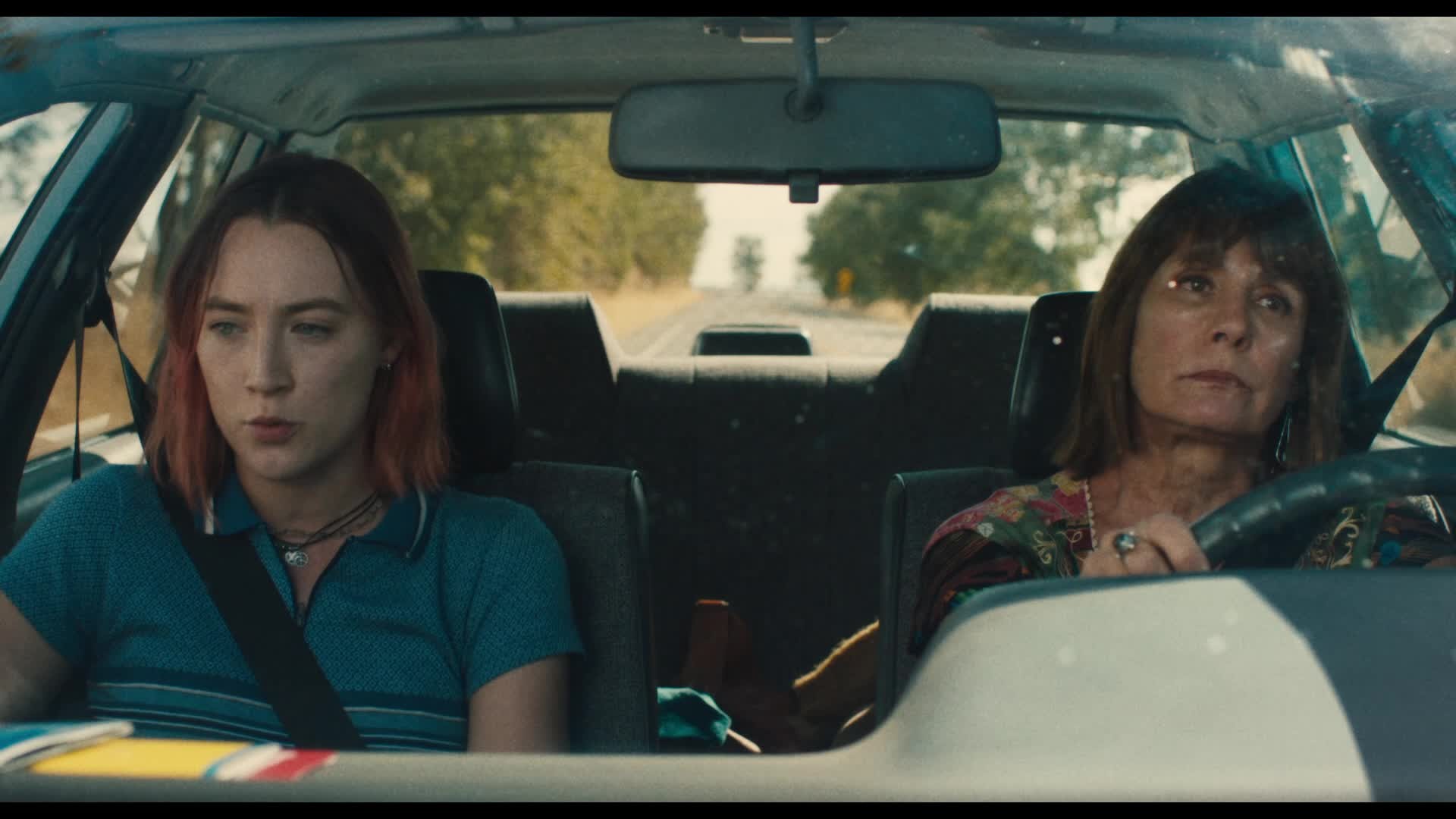

CM: She’s the one who draws him into Fremen society, and their whole relationship is nothing.

MM: Chani is a nothing character, and I hate that because in the book, she’s, immediately depicted as … not aggressive but …

CM: … Assertive.

MM: Assertive and a bit ferocious. But it was the Eighties, and I see a lot of, “We have two attractive leads here, let’s just throw them together.” I also felt like the way Lady Jessica’s presented is not nearly as freaking badass as she is in the book. If I met her in real life, I would be terrified. The Bene Gesserit, I envision them as very intense and intimidating.

CM: You know who was great, though? Stilgar. Javier Bardem plays him in Villeneuve Dune, and he’s fine, but Lynch’s guy [Everett McGill], he is the bomb. His voice is just perfect when he says “Usul” and “Maud’Dib.”

MM: Yeah, but when he’s first introduced, he goes, “I’m Stilgar,” and then he does that weird coughing thing. I was trying hard not to laugh.

MM: The moment I saw Kyle MacLachlan as Paul, especially with the early, young, 15-year-old Paul, I was like, yeah, this is him. He’s so boyish, I even wondered, how long did it take to film this? Because he looks older by the end of it. He looks more distinguished.

CM: It was such hell to film, I think, that everybody like looked older by the time it was over.

Around this time, Craig and Jodi Brewer showed up in Houston’s bar. They joined the conversation with us as they waited for their table.

Craig Brewer: Have you ever seen the David Lynch Dune? 1984?

Jodi Brewer: I don’t think I have. I’ve probably seen clips.

CB: Sting’s in it.

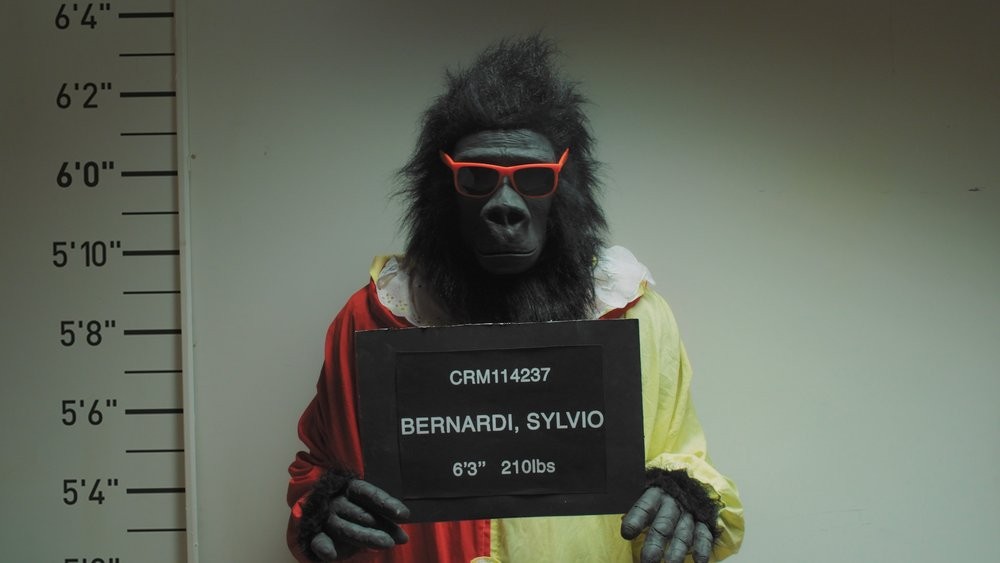

MM: I’m not gonna lie. Sting’s hot. He’s got tiny nipples, but he’s hot.

CM: It’s like prime, Police-era, yoga-body Sting. He’s nearly-naked, and has a knife fight with Kyle MacLachlan.

JB: That’s hot.

CB: So hot.

CM: Mars, would you recommend people watch David Lynch’s Dune?

MM: Absolutely. But I think you should temper your expectations. I think a lot of people are very excited about the Villenueve version coming up. But my recommendation would be doing what I’m doing, and reading the book first

CM: Honestly, it made more sense to you because you’re reading it. If you didn’t have that background, some of it would just be noise to you.

MM: That’s why I say read the book. I do think that, the only frustrating element was, if I had not read the book, I would be lost. I feel like I’m just pushing the book now, but …

CB: It’s great! The book is amazing! It was one of my father’s favorites.

MM: The book made me appreciate the movie so much more. And so I am very excited about the Villenueve version.

CM: He really sticks closer to the book, and he can stretch out and tell the story.

CB: I hope he sticks the landing.

CM: The Lynch Dune is like a beautiful mess. When Lynch is on, he’s on.

MM: This is going in the collection of movies that I love by him now.

CM: If you want to see David Lynch with an enormous budget just going nuts, it works great. But if you’re looking for a coherent movie that makes sense the same way Star Wars makes sense — which is basically what Lynch was signed up to do — no.

MM: No, it does not. But Dune is not Star Wars.