Tavis Smiley recalled it as a defining moment: the day he was given a set of LPs featuring the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr.

Smiley — national broadcaster, talk-show host, and author — was 12 years old when he received those recordings while he recuperated from the beatings he’d received from his stepfather. Growing up in small-town Indiana as a member of a large black family in a largely white community, Smiley hadn’t had King on his radar, but as Smiley said recently by phone from Los Angeles, King did more than change his life:

“He saved my life. He redirected me. In those speeches — in the reassurance of his voice — King talked about the power of love, how love was the only force capable of turning an enemy into a friend. Here I was trying to figure out my life, and I hear King talking about love. He was talking about a nation, but he might as well have been talking to me as a child. I was going to have to love my way through this situation. Hatred was not an option. I would have to love my enemies, love those who used and exploited me, and forgive those I was angry with — including my parents.”

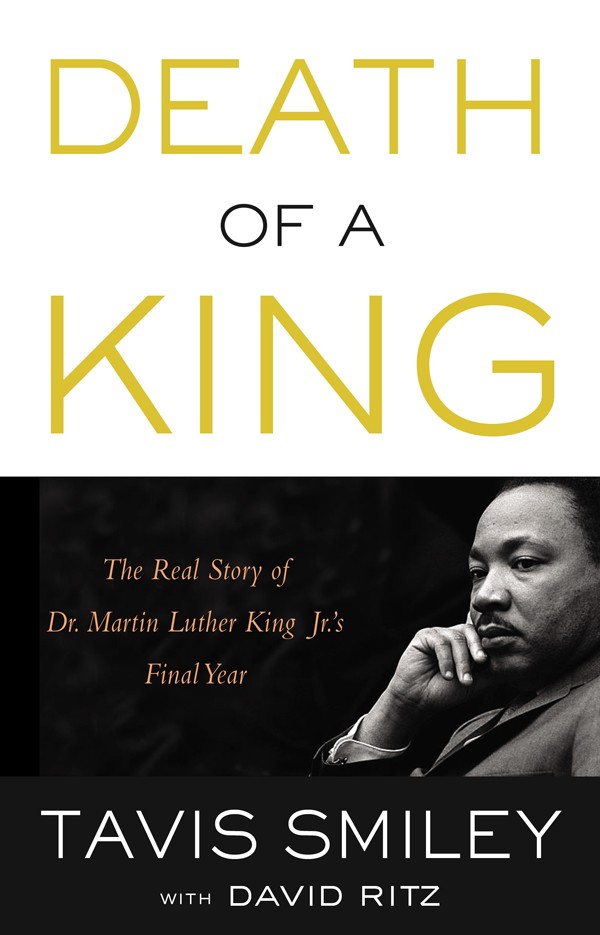

Smiley’s heartfelt response was an answer to why his latest book, Death of a King (Little, Brown), perhaps means more to him than any of his previous books. It was a question asked in anticipation of Smiley’s two upcoming Memphis book signings. He’ll sign and discuss Death of a King on Friday, September 19th, at the Booksellers at Laurelwood at 1:30 p.m. and at the National Civil Rights Museum from 6 to 8 p.m.

It certainly won’t be Smiley’s first time in Memphis. He was here in April to celebrate the National Civil Rights Museum’s redesign (which Smiley said exceeded his expectations). And he certainly doesn’t claim that his Death of a King competes with the “heavy-lifting” of King biographers Taylor Branch, Clayborne Carson, and David Garrow.

What Smiley and his collaborator David Ritz (along with researcher Jared Hernandez) have here, though, is a dramatic retelling of King’s final and pivotal year. What kind of man had King become during those 12 months? That is the question at the heart of the book, and it opens on April 4, 1967, the day the life of Martin Luther King would undergo fundamental change. He was readying for his speech inside Riverside Church in Manhattan — a speech denouncing America’s involvement in Vietnam, the third component in the triple threat to American democracy as King saw it: racism, poverty, and militarism. There were additional, more personal challenges, too, not the least of which the dissension inside the ranks of the civil rights movement and the rise in black-power rhetoric. King’s gospel of nonviolence was losing ground.

“Everybody had turned on him: the White House, the media (including the black media), black organizations,” Smiley said of the difficult position King found himself in. “We may think we know King, but we don’t know him unless we too wrestle with what he endured” — and recognize the toll that the pressure and the tension took on King physically and mentally.

The subtitle of Smiley’s book is “The Real Story of Dr. Martin Luther’s King Jr.’s Final Year,” and that title, Smiley said, is “pushback” on the sanitized, sterilized image some may have of King. But the “real” King will come as no disappointment to readers. It came as no disappointment to Smiley himself:

“It is so rare to come across someone who truly is as advertised — King as truly who I thought he was. That was a beautiful realization for me. But that doesn’t mean King was perfect. He was a public servant, not a perfect servant. At the center of his working witness is this primary mission to love and serve others. He was the real deal.”

And by the time King heard of the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, he was given real hope — hope that he could build a bridge to the movement’s militants; hope that Memphis would direct national attention to the country’s poor of all races.

Death of a King comes with its author’s own hopes. “I’m hopeful that, of all my books, this will be the one that will empower the greatest number of people, will enlighten the greatest number, the book that years from now people will continue to refer to as the most accessible,” Smiley said. “Not the definitive book on King’s last year. That would be arrogant of me. But I want everyday people to understand the real story, the true story of Martin Luther King Jr., the man they maybe do not know.”