Last month, to honor the 55th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the National Civil Rights Museum unveiled “Waddell, Withers, & Smith: A Requiem for King,” an exhibition highlighting three Memphis-based artists whose work responded to King’s assassination and the Civil Rights Movement: self-taught sculptor James Waddell Jr., photojournalist Ernest Withers, and multimedia artist Dolph Smith.

“It goes to show the levels of Dr. King and how many people he impacted,” NCRM associate curator Ryan Jones says of the exhibit. “He didn’t just impact people who were civil rights leaders and human rights activists; he impacted people who were artists. And so this goes to show what he meant as a man and that people here in this great community of Memphis have channeled and responded to something that has been a dark cloud over the city in the past 55 years. Dr. King impacted the hearts and minds of so many citizens.”

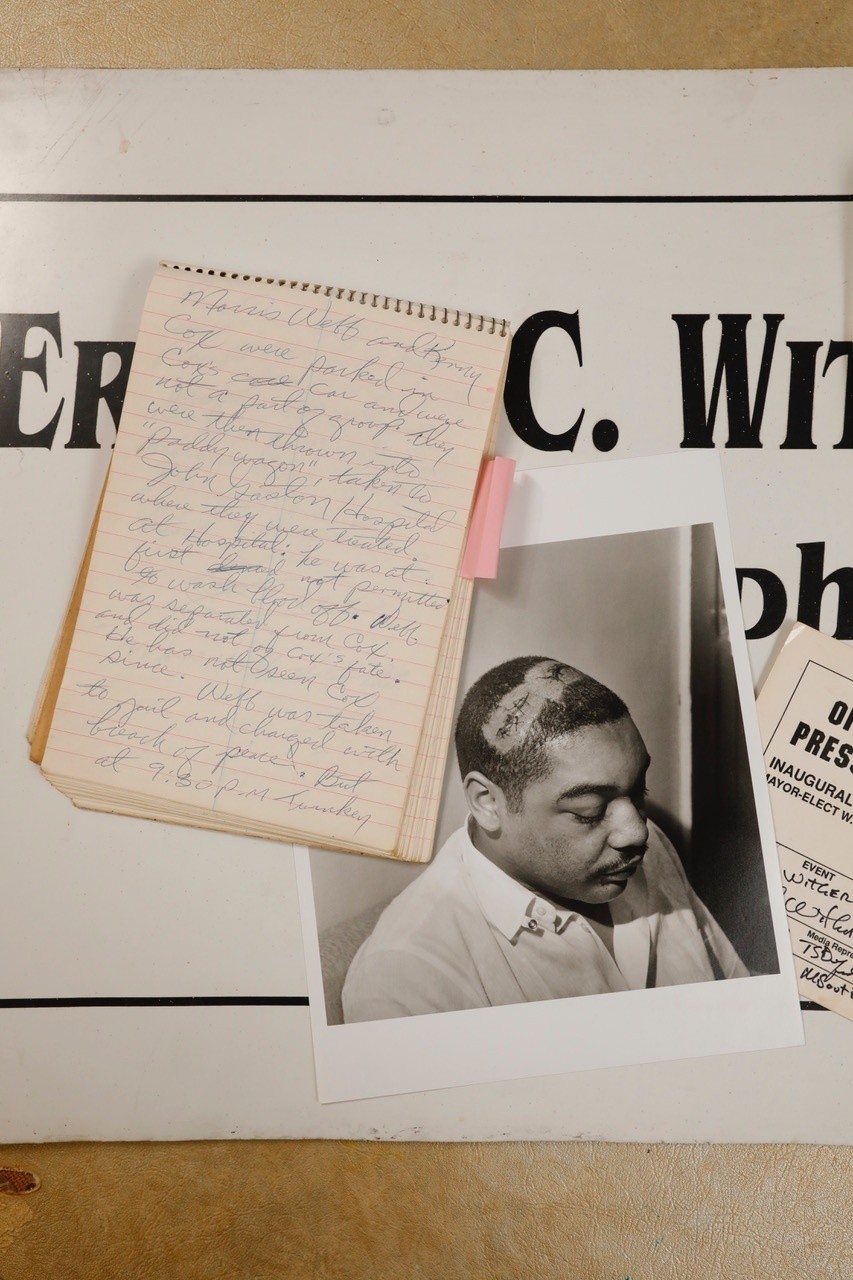

Each of the three artists were born and raised in Memphis, Jones says, and all served in the military, with their respective services being turning points in their artistic careers. Withers, a World War II veteran, learned his craft at the Army School of Photography. He would then go on to photograph some of the most iconic moments of the Civil Rights Movement, including King’s fateful visit to Memphis, the priceless images for which line the exhibition’s walls.

“We can’t tell the story of the modern Civil Rights Movement without the role of photography,” Jones says, and truly, Withers played one of the most significant roles in documenting that history, capturing approximately 1.8 million photographs before his death at 85 years old in 2007.

At the same time Withers was documenting King’s Memphis visit and the aftermath of his assassination, James Waddell (who happened to later be photographed by Withers) was serving in the Vietnam War and didn’t learn what had happened in Memphis until weeks later. For Waddell and his family, King’s death marked a period of pain and grief — “His relatives compared the assassination to a death in the family,” reads the exhibit’s wall text.

“[Sculpture] was his way of reacting to the tragedy that had happened,” Jones says. “He said that living in Memphis and being a native Memphian and not doing the work would be something he would never be able to get over.” So when he returned home, Waddell channeled this grief in the work now on display — an aluminum-cast bust of King and Mountaintop Vision, a bronze statue of King kneeling on a mountaintop with an open Bible. “It shows he’s humbling himself to God,” Waddell said of the sculpture in a 1986 interview in The Commercial Appeal with Anthony Hicks.

Initially, as the 1986 article reveals, Waddell planned to create an eight-foot version of Mountaintop Vision as “the city’s first statue of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” “The time is right, because Memphis is beginning to voice an opinion that there is a need for a statue,” Waddell told The Commercial Appeal. “This will be a tool for understanding.”

Waddell, who has since passed, said he hoped “to see the finished piece placed at the proposed Lorraine Motel Civil Rights Museum, Clayborn Temple, or in Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park.” Though that eight-foot version never came to fruition, at long last, the smaller version of Waddell’s Mountaintop Vision can be seen not only in a public display for the first time, but also at the National Civil Rights Museum as he once had envisioned.

Meanwhile, Dolph Smith, who had long since returned home from the Vietnam War, was in Memphis the night of King’s assassination. As Memphis was set ablaze that night, he and his family stood on the roof of their home, watching the smoke rise around them. He vowed to never forget that date — April 4, 1968. In his personal calendar for that day, he wrote, “If this has happened in Memphis, then now I know it can happen anywhere. It is so hard to believe a man’s basic instinct is to be good.”

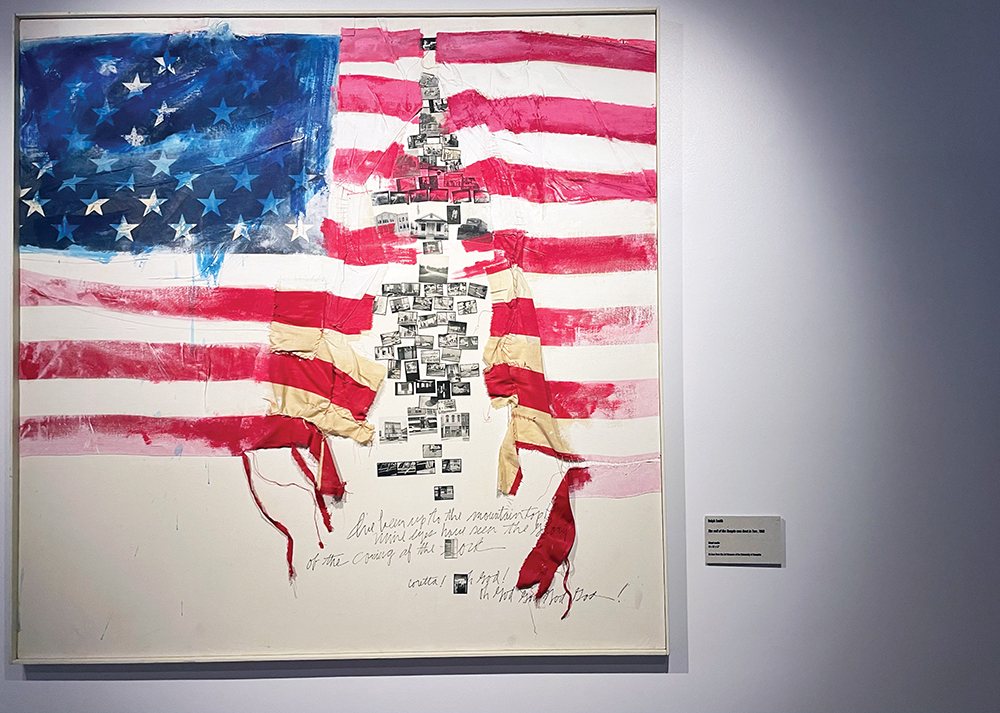

In response to what he called “an unspeakable tragedy” and the public uprising that arose from it, Smith took to the canvas. For one piece on display at the museum, titled The Veil of the Temple Was Rent in Two, the artist ripped an American flag, placing photographs of the Civil Rights Movement in between its tears, as Jones says, “to show the extreme divisiveness that the assassination caused.”

In all, Jones hopes the exhibit will show the reach of King’s legacy extending beyond April 4, 1968, all the way to the present day. In one of the videos projected on the exhibition’s walls, Smith, now at 89 years old, speaks on the importance of witnessing artwork like the pieces on display. “If you make something and it just sits there, it’s unfinished,” Smith says. To him — a painter, bookmaker, and educator — in order for a work of art to be “finished,” it has to be shared, for the mission of the artist is not simply to create but to spark conversation, to encourage self-reflection, and in cases like that of Withers, Waddell, and Smith, to activate progress.

“Waddell, Withers, & Smith: A Requiem for King” is on display at the National Civil Rights Museum through August 28th.

Elise Lauterbach

Elise Lauterbach

Chris Thomas

Chris Thomas  Jim McCarter

Jim McCarter  JB

JB  JB

JB  JB

JB  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Rome Withers

Rome Withers

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  jb

jb