In this week of worldwide remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., focused on his martyrdom here in Memphis, many eminent visitors will have come to celebrate his name and commemorate his mission. One of the first to speak on the subject was Eric Holder, the former U.S. Attorney General under President Obama.

Holder, introduced by the newly elected Democratic U.S. Senator from Alabama, Doug Jones, was keynote speaker at a Monday luncheon at the Peabody held in tandem with a two-day symposium co-sponsored by the University of Memphis Law School and the National Civil Rights Museum.

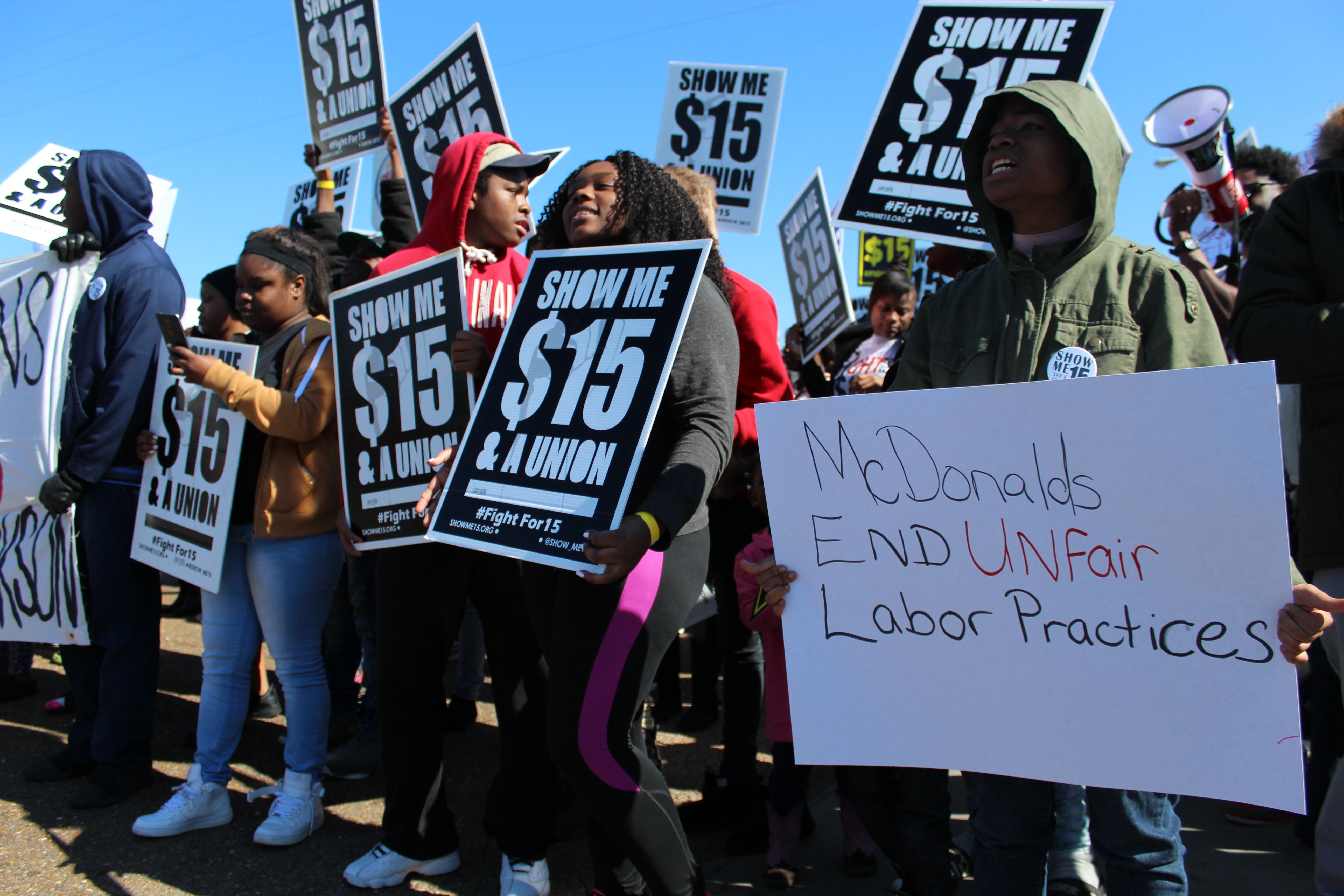

Holder reminded his listeners that, “Dr. King’s dream has not been fully realized,” further noting that there has been backsliding on voting rights, criminal justice reform, and the unexpected re-empowerment of white supremacists and white nationalists. The struggle for social justice, Holder said, remains as difficult as it was during the time of King, who, he noted, was seen by many as a “threatening, polarizing, and disliked figure.”

“The age of bullies and bigots is not entirely behind us,” Holder continued. “We have not yet reached the promised land.” He suggested that, as was the case with King, “it is necessary to be indignant and impatient so that it impels us to take action. … We cannot look back toward a past that was comforting to few. That is not how to make America great.”

Holder was complimentary toward Memphis. “I love this city, its energy, its sense of possibility, and its extraordinary progress,” he said, specifically paying tribute to the 901 Take ‘Em Down movement for its successful agitation to remove symbols of Confederate domination from the Memphis landscape.

But he enumerated several problems still much in need of correcting, including continued economic inequality and systematic voter suppression and gerrymandering.

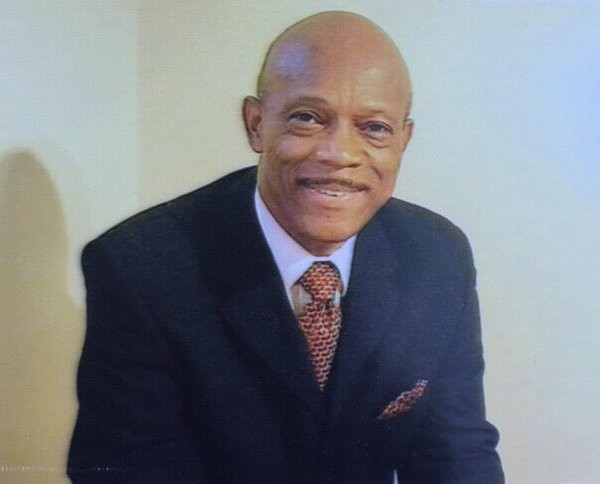

• The subject of voting rights was the subject of one of the most well-attended symposium panels conducted Monday, moderated by UM law professor Steve Mulroy. It was also one of the subjects on the mind of former Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen, now running as a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate and one of the many political figures of note on hand for the MLK50 week of commemorations.

In an interview with the Flyer at the Peabody on Monday, Bredesen mentioned the existence of various “efforts to suppress African American voters [as] one of the things as senator I’d like to address.”

Bredesen said as the former state’s chief executive, he was able to solve vexing problems by governing from the middle, working with both parties, including those he called “economic Republicans.” If elected Senator, he said he would continue in that vein.

As a successful health-care executive before entering politics, Bredesen said he would address the issue of the nation’s medical insurance system, currently at risk because of uncertainty about the fate of the Affordable Care Act. “The act is still on the books,” he said, “and we’ve got to make it work. As was the case with Medicare and Social Security,” he added, “it requires modifications.”

Bredesen sees his ability to compromise across the political aisle as an asset in his forthcoming Senate race against expected Republican foe, the ultra-conservative U.S. Representative Marsha Blackburn, whom he currently leads in statewide polls.

• Meanwhile, retiring incumbent Republican Senator Bob Corker, the man whom Bredesen and Blackburn would replace, was also in town, addressing members of the Rotary club of Memphis on Tuesday and warning of a spendthrift Congress and the importance of the Iran nuclear pact. “The President should know: you can only tear up the agreement one time,” he said. (More at memphisflyer.com, Political Beat blog.)