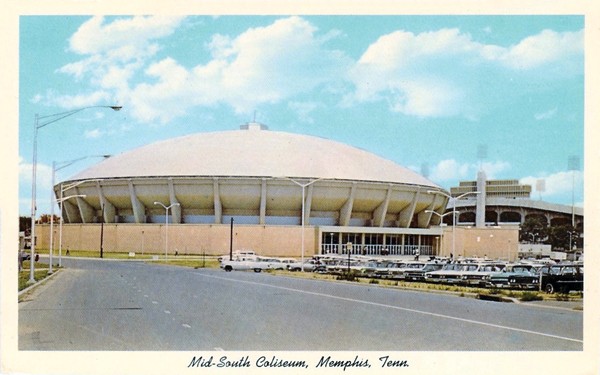

Echoes from my boot heels clicked thinly off the asphalt and bricks outside the Mid-South Coliseum. I paused and looked way up to its domed roof before I walked in. Driving up Southern Avenue was the closest I’d ever been to the building before. My only real fascination with it now was story research. I had no idea why anyone would want to save the Coliseum — or tear it down. I had no idea I’d find the answers to both questions under the big dome.

The service entrance was open on the east side. It was the large, roll-up gate where 18-wheelers would load in lights and sound gear for concerts. I stepped forward and my foot falls were muffled as I passed through the tunnel and into the still air and massive darkness of the Coliseum’s dome.

Photographs by Brandon Dill

Photographs by Brandon Dill

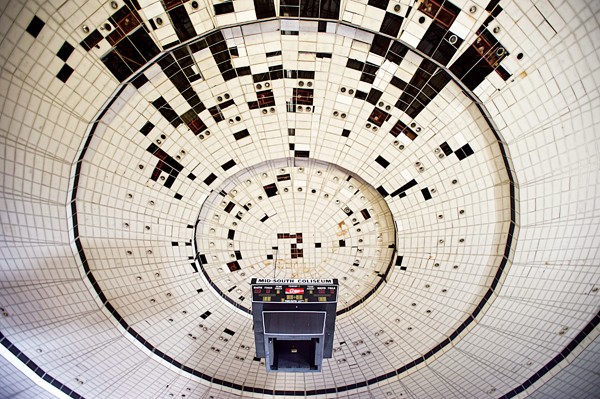

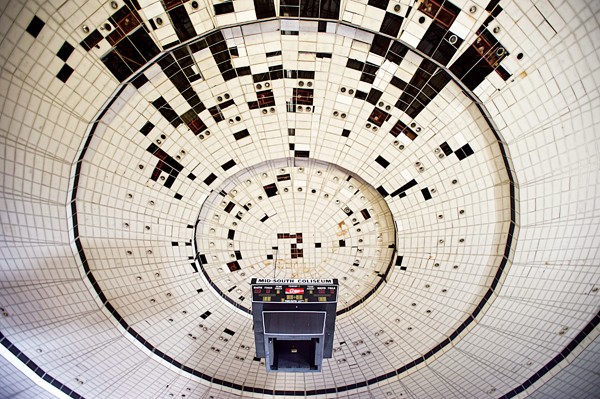

A shaft of light from the door exposed three or four white semi-truck trailers parked close to the center of the floor. They sat under the old scoreboard, which was analog but still big by today’s standards. I knew the trailers housed the pieces of the old Memphis Grand Carousel, now destined for the Children’s Museum of Memphis. But what made me pause was how easily the Coliseum swallowed those huge truck trailers.

I touched base with the city official who had let us all in — a television news crew, a video production team, reporters and a photographer from The Commercial Appeal, and me. The official said to just go and look at whatever I wanted, a golden permission slip.

Pictures of what’s left inside the Coliseum.

Crumbles of loose black material (that looked like dirt but weren’t dirt) were scattered over the floor, but the place wasn’t as much dirty as it was cluttered. Stacks of chairs; rolls of chain link fence; paisley couch cushions stacked on pallets; a giant red “M” peeking out of a crate. Kyle Veazey, the CA‘s politics team leader, told me it was the old “Memphis” sign from the now-demolished Lone Star concrete plant downtown.

Tiles were missing from the once-white ceiling. It reminded me somehow of the incomplete Death Star from Return of the Jedi. Nails and bits of metal clinked away from my boots as I walked. I clicked on my phone’s flashlight.

Outdoor light shone through on the west side of the floor. The concourse looked like it had been just closed the night before. With a broom and a mop, the place would be ready for guests. Several office windows were shattered, vandalized. Fluorescent light bulbs stuck out of the tops of trash cans. The entrance doors had been broken and boarded up.

On the second level, rows and rows of empty seats sat folded. I unfolded one and sat down. Veazey laughed and reminded me how dusty and/or moldy I’d be. I jumped up, thinking of the decade of mold on my back and the slow death that was sure to follow. But even in the brief time I sat in the chair, I could imagine seeing a show or a graduation there.

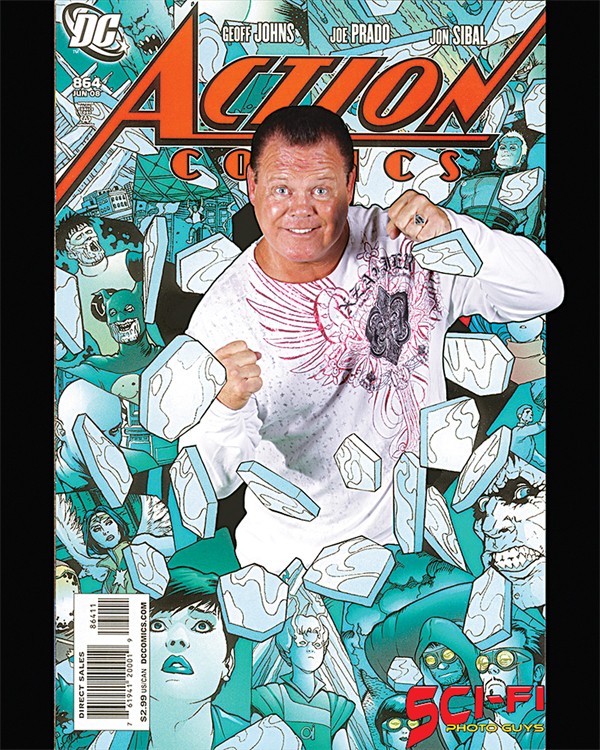

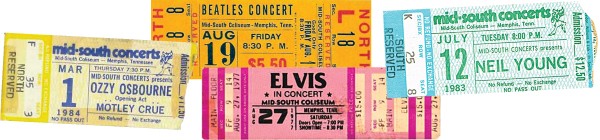

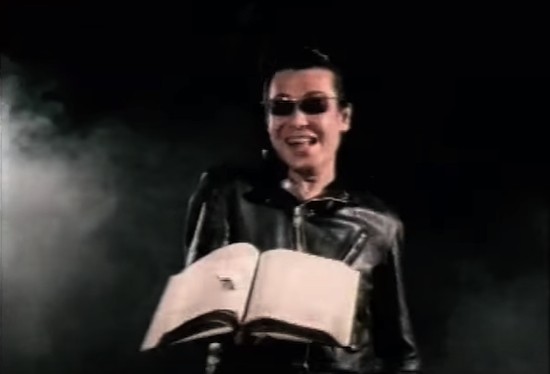

The day before I’d seen a photo of the Beatles playing the Coliseum. I mentally overlaid the image where I thought it should go. I mentally replayed the YouTube video of Jerry Lawler’s and Terry Funk’s “empty arena” wrestling match in 1981. I imagined David Copperfield making 13 audience members disappear in his 2001 “Tornado of Fire” television special. And then I thought about the last show, in 2006 and how the final sounds at the Coliseum were the Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s heavy metal Christmas music.

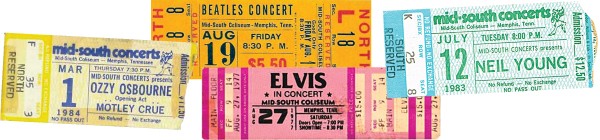

Old tickets to Coliseum events

I remembered another internet picture of Cher and her then-husband Gregg Allman walking from a Coliseum dressing room. I wanted to see those dressing rooms. A single fluorescent bulb flickered and buzzed down a long dusty hallway, like something out of a creepy video game. A boiler somewhere knocked and moaned, right out of Scooby-Doo. I saw a flash to my right and found CA photographer, Mike Brown, shooting in the only dressing room with any light.

I poked my head into a team dressing room down the hall. It had a king-sized mattress and a weathered copy of Vibe magazine that asked: “Is Mase for real?” Then I spotted a concession stand with an open door. A dried up bag of nacho cheese. A stack of Bud Light cups from three logos ago. And a menu board: Large Coke = $3. Draft beer = $4. Nachos = $3. Polish dog = $3. Underneath the prices and the logos, someone used the letters to write “EAT SHIT THANKS”

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

I understood why people want to save the Coliseum. It’s huge, it doesn’t seem to be in terrible shape, and there are a lot of great memories in there. But its size seems to equal the behemoth effort it would take to bring it back to life and actually make a go of a successful business inside.

But it’s a place big enough for dreamers, and the Coliseum is the center of a dream for a cadre of Memphians who believe that the place where so much of the city’s music, sports, and entertainment history happened should be preserved.

Robert Lipscomb, the city’s director of Housing and Community Development, also has a dream for the Fairgrounds, and the Coliseum doesn’t belong in it.

No one knows yet what will happen when those dreams collide.

Save the Coliseum

The Mid-South Coliseum should be saved, not just because it holds a lot of history, but also because there’s a good potential use for the building that speaks to the city’s brands in music, wrestling, and basketball.

That’s the vision of members of the newly formed Coliseum Coalition, a group that has organized a grassroots but sophisticated movement to save the building and ensure public input is heard on any plan to redevelop the Fairgrounds.

The group (and general sentiment against the proposed youth sports complex at the Fairgrounds) is growing. The Save the Mid-South Coliseum Facebook group has swelled to 3,540 members in a few weeks. The official Mid-South Coliseum Facebook page has more than 11,000 likes.

“We think it would be shortsighted to raze the Coliseum to pursue what we think is a fairly poorly thought-through plan that might leave tax payers on the hook and might leave Midtown with something it doesn’t want,” said coalition member Marvin Stockwell. “For that, we’re going to sacrifice a place that contains not only so much history — music history, especially, which is Memphis’ strongest brand — but basketball for sure. Before we had the Grizzlies, we had the Tigers. And then wrestling, I mean [Jerry] Lawler fought Andy Kaufman there. It’s not just the memories, it’s the possibility.”

Stockwell, and Coalition members Mike McCarthy and Jordan Danelz, gathered last week to talk about the Coliseum at Cooper-Young’s Java Cabana, a stone’s throw from the building they’re trying to protect.

The three wanted to clear up a few things from recent media reports: their efforts are not fueled entirely by nostalgia, they’re not fighting progress at the Fairgrounds, but it is true they don’t have a clear idea of what the Coliseum should be or even could be.

What they do believe is that the building should be saved. They point to the success of revitalization projects such as the Chisca Hotel, the Sears Crosstown building, the Tennessee Brewery, and Broad Avenue. They say that government leaders should listen to the community, especially those who would be neighbors to the proposed youth sports complex for the next 30 years of the proposed Tourist Development Zone (TDZ).

Memphis is missing out on major opportunities by keeping the Coliseum closed, McCarthy said, noting that his daughter recently saw Jack White at Snowden Grove in Southaven, Mississippi.

“We live right over there on Nelson,” McCarthy said. “I could’ve just walked over there with her to the Coliseum to see the show and every bit of tax money — or money, period — that was spent could’ve been generated inside Midtown. The Coliseum could be the largest tax generator in Midtown, given the opportunity.”

The big snag there is the non-compete clause in FedExForum’s contract with the city of Memphis. The clause says an “important element of the success of the Arena Complex is to limit direct competition” from the Coliseum or the Pyramid. It mandates any show with more than 5,000 seats is the sole property of the Forum.

The Coliseum has more than 11,000 seats. Coalition members are still analyzing the language of the non-compete. Does it affect only new places, or renovated places, or both? But it’s a huge question that hampers the way forward for any new idea the group may have for the Coliseum.

“That’s why you’re at a disadvantage when you try to say what it could become,” Stockwell said. “That’s an unbelievably huge variable that’s going to make you go one way or another.”

But ideas are there for the Coliseum, and they keep coming: A rock-and-roll museum. A brewery. Give it to the University of Memphis Tigers. A music venue. An ice skating rink. A basketball museum. A soundstage for local film and television production. A wrestling museum. A rehearsal hall for touring acts.

A city report puts the price tag at about $32.8 million to bring the Coliseum back to working order. The largest chunk of the money ($8.6 million) would be spent just to get it current with the Americans with Disabilities Act. But McCarthy doesn’t trust the figure.

“If the Liberty Bowl was saved for what [former Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton] said was going to be $50 million, which turned out to be $9 million, then the Coliseum can be saved for probably $9 million or $10 million as well,” McCarthy said. “That’s not just pulling a figure out of the air. That’s based on the Liberty Bowl, which was built at the same time with the same reinforced steel and concrete and everything else.”

Danelz said the youth sports complex idea (at the heart of the current Fairgrounds redevelopment plan) has failed in numerous cities across the country. He said the current process has not been transparent and criticized Memphis Mayor A C Wharton’s plan to get the TDZ first and divulge a more detailed plan later.

“They’re saying, don’t worry about it; let’s get that money and then we’ll figure out what we’re doing,” Danelz said. “In what Business 101 class can you say, ‘Let’s get a loan and then figure out a business plan’? Would you pass that class?

“Yet, here you have the highest power in our city government saying exactly that for $220 million. They have nothing on the table to show us — no blueprints, no private partners, nothing.”

Wharton and Lipscomb have seemingly hit the pause button on the project for now and the Coalition members said it’s a welcome sign. They hope to have planning sessions with community members, conversations with Lipscomb about the Fairgrounds plan, and some pre-vitalization events (a la Brewery Untapped or New Face for an Old Broad) to bring people to the Coliseum and get them dreaming about its potential.

“If you went to Orange Mound, Belt Line, Edwin Circle, Cooper Young, you would be sorely pressed to find any citizen of Memphis who wants to tear down the Coliseum,” McCarthy said. “This is all coming from the top down. We’re better than that.”

Tear it Down

The Mid-South Coliseum should be razed because it’s too costly to renovate and it doesn’t fit in with future development plans at the Fairgrounds.

That’s according to city officials who believe the Coliseum has to go in order to move forward on the proposed Tourism Development Zone retail and youth sports complex at the Fairgrounds. It’s a point that does not seem to delight to Robert Lipscomb, the city’s director of Housing and Community Development, but he’s repeated that the demolition is an integral part of making the Fairgrounds a sports and retail tourist destination.

Back in 2009, O.T. Marshall Architects said it would cost about $29.5 million to fix the Coliseum. They looked at everything from drywall and kitchen equipment to plumbing and sprinklers.

A year later, O.T. Marshall revised the figure to about $32.8 million. They said the building would have to be brought up to Americans with Disabilities Act standards ($8.6 million), get seismic structural updates ($5 million), get a new roof ($550,000), new flooring ($2 million), and general code updates in mechanical, plumbing, electrical, and fire protection and alarms ($9 million).

Code Solutions Group LLC analyzed code issues inside the Coliseum in 2009. They found that the layout of the building creates a “dangerous condition in the event of an emergency.” A plan to fix the problem would require 168 sections of hand rails, dozens of new stair steps, replacing the ceilings inside the arena and in the concourse, more than a dozen new bathrooms, adding a new lighting system, adding a sprinkler system, and more. The report noted that the building is a “landmark” but questioned if the costs of upgrades to the Coliseum would better serve Memphis than a new building.

“If a dedicated performing arts venue, seating 8,000 to 12,000 people is needed, then a new building with a full working stage, fly gallery, proscenium protection, good acoustics, theatrical lighting, and adequate exit capacity for the designed seating, and with full sprinkler protection might be the right answer,” said the 2009 report. “While the Coliseum is a unique building, there is physically no way a 1960s multi-functional facility could be redesigned to provide this type of venue.”

During the final three years of its active life, the Coliseum lost more than $880,000, according to city documents. In 2006, it was on course to lose at least $300,000.

So, city leaders looked closely at the Coliseum. In 2006, they were hoping to attract new events such as hockey, soccer, or arena football, but only if the tenants could work within the terms of the FedExForum’s non-compete clause.

They considered new federal tax credits to keep the Coliseum going. They considered the pros and cons of demolishing it or even building a new structure. In the end, the Coliseum was mothballed. It’s now used primarily as storage for truck trailers containing the Memphis Grand Carousel.

Lipscomb said the building has been in “full shut-down” since around 2006, meaning limited utilities and no heating or cooling. He told the Memphis City Council earlier this month that he has been in talks with the Coliseum Coalition and will continue to talk with them about efforts to save the building.

“I don’t have a dog in the fight one way or another,” Lipscomb said. “I just want to make sure that whatever we construct — either the renovation of the Coliseum or a new building — satisfies the needs for our future.”

To Lipscomb, that future includes getting into the youth and amateur sports business. It’s the cornerstone of his plan for the redevelopment of the Fairgrounds that also includes, a hotel, retail shops, and restaurants.

“Youth sports” include indoor activities such as basketball, volleyball, cheerleading, gymnastics, track, and more. Those sports require what Lipscomb calls a multi-purpose building — one that can be transformed inside to accommodate all the different sports, and “the Coliseum is not feasible as a multi-purpose building.”

Kevin Kane, president of the Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau, concurred. “If you want a first-class indoor youth sports complex, you cannot physically do that inside the Coliseum,” Kane told council members. “I’m not an architect, but I can tell you, you can’t do it. Even if you gut it out, you can’t make the Coliseum where you can have six or seven basketball courts in there. There’s no way.”

Kane’s comments came after a question from councilmember Harold Collins, who said he envisioned a new building that could be used for youth sports and then changed to house concerts and even large high school graduations. Kane told him youth sports is one thing, “but if you want an arena, maybe you should figure out a way to fix the Mid-South Coliseum.”

Other council members questioned Lipscomb on the viability of the youth sports market. He pointed to a letter he said he got from Amateur Athletic Union President Dr. Roger Goudy that Lipscomb said it read, basically, “if you build it, they will come.”

“I know a lot of people have been critical [of the youth sports idea] but there’s a big market for that, still,” Lipscomb said. “So we have a great opportunity for that.

“Some people will say we missed the boat on that. They’ll say, Memphis is not positioned to be a youth and recreation sports team and amateur athletics city. So, I think this letter dispels that myth.”

But the Coliseum still stands. City officials have taken a step back and invited the Urban Land Institute to have a look at their plans and the Fairgrounds, to determine if the two are a match.

Council members also made it clear to Lipscomb earlier this month that any development at the Fairgrounds will first need the council’s approval.

Photographs by Brandon Dill

Photographs by Brandon Dill

Toby Sells

Toby Sells