These days, it seems that film discourse is dominated by discussions about the future. But while there are real issues facing the unique combination of art and commerce we call cinema, there’s more to movies than just the multiplex — and that’s what Indie Memphis has specialized in for the last 25 years.

“We are kind of in our own lane,” says Executive Director Kimel Fryer. “Indie Memphis is like no other film festival, because Memphis is like no other city.”

Indie Memphis was founded in 1998 by a group of University of Memphis film students led by Kelly Chandler. Known then as the Memphis Independent Film Festival, it attracted about 40 people to a Midtown coffee shop, where they watched student movies projected on a sheet hung on the wall. Nowadays, the annual festival boasts an attendance of more than 11,000, and the organization hosts programming and events year-round, such as the monthly Shoot & Splice programs, where filmmakers provide deep dives into their craft. The Indie Grants program was created in 2014 to help fund Memphis-made short films. The Black Creators Forum began in 2017 to help address the historic racial inequalities in filmmaking. During the pandemic, Eventive, a Memphis-based cinema services company that began as Indie Memphis’ online ticketing system, pioneered the virtual programming which is now an established feature of film festivals worldwide.

“It took 25 years for Indie Memphis to become an organization that reflects the city,” says Artistic Director Miriam Bale. “But each step along the way has added to what makes it special now.”

A New Leader

Kimel Fryer took over as Indie Memphis’ new executive director only a few weeks ago. But she is no stranger to either Memphis or the world of independent film. She’s a West Tennessee native whose mother has taught at Oak Elementary since the mid-1990s.

“My mom was always tough on me, and I’m grateful for it because I ended up kind of inheriting that from her,” she says. “In my mind, I’m supposed to reach for the stars. I’m supposed to overachieve.”

Fryer holds graduate degrees in law and business from the University of Memphis and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. She has worked for companies as diverse as Lincoln Pacific and Pfizer, and left FedEx to take over the reins of Indie Memphis when Knox Shelton resigned after only a year on the job. The mother of two saw it as an opportunity to merge her professional life with her passion for film. “When I was working for Chrysler, I realized that I had this amazing job that I worked my butt off for,” she says. “It was a great company with great benefits. But I was depressed. If I wanna be completely honest, it was one of the saddest periods of my life.”

Growing up, Fryer had tried her hand at writing, and she had been involved with theater and band programs in high school and college. In Detroit, she found a new outlet for her creativity when she volunteered as casting director for filmmaker Robert Mychal Patrick Butler’s Life Ain’t Like the Movies. “The independent film world is very visible in Detroit,” she says.

When she landed Coming 2 America star Paul Bates for a role in the film, Butler promoted her to producer. “I said, ‘What is a producer?’ He said, ‘You’re kinda already doing it.’”

Fryer wrote and directed her own short film, “Something’s Off,” which will screen at Indie Memphis 2022. She says she got her acceptance email just a few weeks before she found out she was going to be the new executive director. “I’ve found this career where I could kind of wrap all my skills into one job,” she says. “I could actually be my full self all the time, which is really my dream.

“I’m very eager to learn and eager to meet other people, understand how they do things. But I’m also cognizant of the fact that I am coming back to Memphis, and we’ve always been a different city that has marched to the beat of our own drum. We’ve got to continue that as we continue to grow and strive for greatness in the film community. I’m really excited about what’s next. I believe in Indie Memphis. I believe in the staff. I believe we are headed towards a great film festival.”

The Picture Taker

From the 1950s to his death in 2007, it seemed that photographer Ernest Withers was everywhere. “We keep calling him a Zelig-like figure or like Forrest Gump,” says Phil Bertelsen, director of Indie Memphis 2022’s opening night film The Picture Taker. “He was at every flash point in Civil Rights history, and then some.”

Withers was a tireless documenter of Black life in the South. His work even appeared in publications like Jet and the Chicago Defender. “Some of my favorite photos of his are street portraits — the photos he took of everyday people just going about their daily business,” says Bertelsen.

“I think what made him almost like a father figure in Memphis was the fact that he recorded his community’s lives literally from birth to death,” says producer Lise Yasui. “He left behind an estimated 1.8 million photos. They are of every major event in every family’s life — as we say, it’s celebrations as well as sorrows. He locked that into their histories and made sure that they had these records of the lives they lived. Those photographs are really beautiful. They have an intimacy that can only come from someone inside the community.”

Three years after Withers’ 2007 death, Commercial Appeal reporter Marc Perrusquia revealed that the trusted photographer had been a paid informant for the FBI. The news came as a shock to many in the community, who saw it as a betrayal of the Civil Rights activists who had trusted Withers. “When you go behind the headlines and the surface of it all, you recognize that there’s a lot of nuance and complexity to that choice that he made at that time,” says the director. “What we attempted to do with the film is to try to understand that time, that choice, and the man who was at the center of it all.

“I think it could be said, without question, that Ernest was a patriot who believed in the hope and promise of this country,” continues Bertelsen. “Don’t forget he was a fourth-generation American war veteran.”

Withers was far from the only one talking to the FBI — their reports refer to him as source #338. “I had the privilege and the workload of reading as many of the FBI files as we could get our hands on,” says Yasui. “They tell a story that’s pretty intense and really detailed in terms of names, places, affiliations, and friendships — everything down to personal gossip. The other thing that you have to understand is they are FBI records written by FBI agents. So there’s not a single document in the 7,000+ pages that I’ve read that is a direct quote from Ernest himself. It’s always through the lens of his FBI handler. That’s not to say that what he wrote was not accurate, but it’s filtered through their agenda, which was to root out radicals who were allegedly inside the Civil Rights movement. …We heard testimony that he basically kept people from harm’s way because he knew what he knew. But at the same time, he damaged the reputations of people by informing on them. It was a double-edged sword that he was wielding.”

Ironically, it’s people like Coby Smith, a member of the Memphis-based Black Power group The Invaders, prime targets of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, who defend Withers in The Picture Taker. “He was a man of great reputation and appreciation,” says Bertelsen. “In fact, we were hard-pressed to find anyone who had anything negative to say about him, even after it was shown that he informed on them.”

For Bertelsen and Yasui, this is the end of a six-year journey. “We are so grateful to the many people of Memphis who helped us get this story, especially the family who really took a leap of faith by trusting us with his images,” says Bertelsen. “They’ve had to face some very painful revelations about their patriarch, and they’re still facing them. I think it shows a certain amount of grace and trust and understanding. There are a lot of ways you can interpret this story, and they haven’t shied away from the truth. They told us they learned things about their dad that they didn’t know before, through this film. That’s very gratifying to us.”

The Poor & Hungry

In 2021, Craig Brewer directed Coming 2 America. It was his second collaboration with comedy superstar Eddie Murphy, and the biggest hit in the history of Amazon Studios.

In 2000, the biggest job Brewer had ever held was a clerk at Barnes & Noble bookstore. That was the year his first feature film, The Poor & Hungry, premiered at Indie Memphis. “I still feel that it was the biggest premiere that I’ve ever been to, and the one with the highest stakes,” he says. “Winning Best Feature for 2000 is still the greatest award I can ever remember winning in my life. … The festival back then was a beacon. It was the North Star. We were all making something so we could showcase it at Indie Memphis. It’s something I hope is still happening with the younger filmmakers today. I had another short that year called ‘Cleanup In Booth B.’ It was a big, productive time for me. But it was also the first time ever to see my work being shown in front of people at a movie theater.”

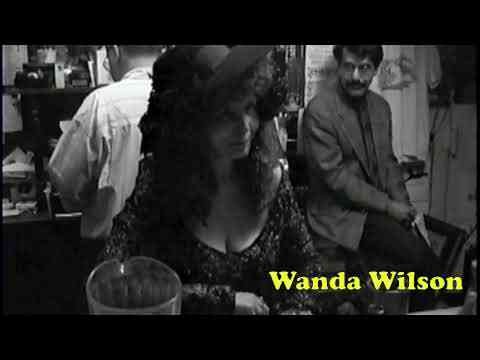

The Poor & Hungry is the story of Eli (Eric Tate), a Memphis car thief who accidentally falls in love with one of his victims, a cellist named Amanda (Lake Latimer). The characters’ lives revolve around the P&H Cafe, a legendary Midtown dive bar which was run by the flamboyant Wanda Wilson, who plays herself. To call the black-and-white feature, shot with a handheld digital camcorder, “gritty” is a massive understatement. But Brewer was able to wring some striking, noir-like images from his cheap equipment, and the film features a series of great performances, most notably Lindsey Roberts’ stunning turn as Harper, a lesbian street hustler.

“I think what I got right on it is something that I tried to carry over to Hustle & Flow, which was, how do you create characters that, if somebody were to just describe them to you, you would say, ‘I don’t think I would like them’? But then, when you start watching them in the story, you find that you not only love them, but you want them to succeed, and you feel for them when they’re in pain.”

Made for $20,000, which Brewer inherited when his father Walter died suddenly of a heart attack, The Poor & Hungry would go on to win Best Feature at the Hollywood Film Festival, defeating films which had cost millions to produce. It got his foot in the door in Hollywood and earned him the opportunity to direct his second feature film Hustle & Flow, which was nominated for two Academy Awards, winning one for Three 6 Mafia’s song “It’s Hard Out Here For A Pimp.”

The Poor & Hungry will return to the festival where it premiered as part of Indie Memphis’ 25th anniversary celebration. “When I look at it now, I view it as an artifact of a time in Memphis. There are so many places that aren’t there anymore. The P&H Cafe that it’s named after is no more, and Wanda has left this planet in bodily form but remains in spirit. I’m so glad that I captured all that. It’s good to see a Memphis that may not be there anymore. But most importantly, I hope people come see it because it’s the movie that I point people to when they say that they want to make a movie but they think it’s impossible. Well, I made this with just a small camcorder, a microphone, four clamp lights, and a lot of effort.”

Hometown Heroes

It’s a bumper crop year for the Hometowner categories, which showcase films made here in the Bluff City. In addition to anniversary celebrations of Brewer’s The Poor & Hungry and this columnist’s punk rock documentary Antenna, nine features from Memphis filmmakers are screening during the festival.

Jookin is Howard Bell IV’s story of an aspiring dancer caught up in Memphis street life. The ’Vous by Jack Porter Lofton and Jeff Dailey is a documentary about the world-famous Rendezvous restaurant. Ready! Fire! Aim! is Melissa Sweazy’s portrait of Memphis entrepreneur Kemmons Wilson, founder of Holiday Inn. Show Business Is My Life — But I Can’t Prove It by G.B. Shannon is a documentary about the 50-year career of comedian Gary Mule Deer. Michael Blevins’ 50 for Da City recounts Z-Bo’s legendary run as a Memphis Grizzly. Cxffeeblack to Africa by Andrew Puccio traces Bartholomew Jones’ pilgrimage to Ethiopia to discover the roots of the java trade. United Front: The People’s Convention 1991 Memphis is Chuck O’Bannon’s historical documentary about the movement that produced Memphis’ first Black mayor. Daphene R. McFerren’s Facing Down Storms: Memphis and the Making of Ida B. Wells sheds light on the Black journalist’s early years in the Bluff City. The Recycle King is Julian Harper’s character sketch of fashion designer Paul Thomas.

On opening night is the Hometowner Narrative Shorts Competition. In recent years, this has been the toughest category in the entire festival, where Memphis filmmakers stretch their talents to the limits for 10 minutes at a time.

Janay Kelley is one of eight filmmakers whose works were chosen to screen in the narrative shorts competition. A junior at Rhodes College, she’s a product of the Indie Memphis CrewUp mentorship program, and two-time Grand Prize winner at the Indie Memphis Youth Festival. “This is my first film festival as an adult,” she says.

Kelley’s film is “The River,” an experimental marriage of imagery and verse. “My grandmother told me once that the river that you got baptized in could be the same river that drowns you in the morning. I like that dichotomy of healing and of destroying, of accepting new people into your life and saying, ‘Will you help me or will you harm me?’”

Kelley provides her own narration for the film, which was based on a prose poem she wrote while still in high school. “I take a lot of inspiration from my Southern heritage, especially from the women in my family,” she says.

The visuals reference several Black artists of the 20th century, especially the painting Funeral Procession by Ellis Wilson, which was famously featured on The Cosby Show. Kelley treats the many women, young and old, who appear in the film with a portraitist’s touch.

“Before I started in films, I was really into photography, and you can see a lot of that still in my work,” she says. “I come from a very poor background. There is a specific picture of my mother, my grandmother, and my aunt, and they got it taken at the fair. Back in the day, they used to take people’s portraits there, so some families would get dressed up to go to the fair to get their portraits taken, because they couldn’t afford to get it done any way else. What you need to know about being poor and Black in the South is that a lot of us don’t live long. So some of the stories I’ve heard about my family members, I’ve heard after they have died, and I’ve had to kind of stare at their pictures. I think it comes out of a genuine love of the history of photography, and what it meant for people like me.”

Witchcraft Through the Ages

Indie Memphis’ October spot on the calendar means that it coincides with what Bale calls “the spooky season,” when many horror movie aficionados embark on a monthlong binge watch. For this year’s festival, Bale programed a pair of rarely seen horror classics that have significant anniversaries. The first is Ghostwatch, a British mockumentary which debuted 30 years ago.

In the tradition of Orson Welles’ infamous Halloween radio broadcast of “War of the Worlds,” Ghostwatch was presented as a Halloween special in which real-life BBC journalists Sarah Greene and Craig Charles would broadcast a live investigation of a supposedly haunted house. But their goofy Halloween jokes turn serious when the house’s real ghosts show up and start causing mayhem. When it was first broadcast on Halloween night in 1992, the BBC switchboard was jammed with more than 1 million calls from viewers concerned that their favorite newscasters were being slaughtered by ghosts on live television. “This is a staff favorite,” says Bale.

The second Halloween special is Häxan, which has its 100th anniversary this year. Indie Memphis commissioned a new score for the silent film from Alex Greene, who is also the music editor for the Memphis Flyer. For this performance, Greene’s jazz ensemble The Rolling Head Orchestra — Jim Spake, Tom Lonardo, Mark Franklin, Carl Caspersen, and Jim Duckworth — will be joined by theremin virtuoso Kate Taylor. “We’ve been wanting to work with Alex for a long time, and this was a great opportunity,” says Bale.

Director Benjamin Christensen based Häxan on his study of the Malleus Maleficarum (“The Hammer of Witches”), a guide for clergymen conducting witch hunts, published in 1486. Upon its premiere in 1922, Häxan was the most expensive silent film made in Europe. Christensen’s meticulous recreations of witches’ Sabbath celebrations, complete with flying broomsticks and an appearance by a mischievous Satan (played by the director himself), still look incredible. Its frank depictions of the Inquisition provide the horror. “I was shocked by how much of it is framed by the torture of the witches,” says Greene. “It implies that a lot of this crazy behavior they described was just victims trying to make up anything to stop the thumbscrews.”

Released a decade before Dracula ushered in the modern horror era, Häxan is a unique cinema experience. “I think of it as kind of like Shakespeare’s time, when the English language was not as settled in spellings and meanings of words. It was a fluid language,” says Greene. “This film came at a time when the language of cinema was very fluid and kind of up for grabs, which is why you could have this weird hybrid of documentary/reenactment/essay.”

“It’s within the Halloween realm, but not necessarily a horror movie,” says Bale. “That’s part of what’s so interesting about it. There are some silent films that just feel so fresh, they could have been made yesterday. Häxan is one of those.”

The 25th Indie Memphis Film Festival runs from October 19th to the 22nd at the Orpheum Theatre’s Halloran Centre, Crosstown Theater, Black Lodge, Malco Studio on the Square, The Circuit Playhouse, Playhouse on the Square, and virtually on Eventive. Festival passes and individual film tickets can be purchased at indiememphis.org. The Memphis Flyer will feature continuing coverage of Indie Memphis 2022 on the web at memphisflyer.com.