Chris Ellis will be in Memphis on August 24th to host the 25th installment of the Ostrander Awards, ArtsMemphis’ and Contemporary Media’s annual party honoring the best of Memphis Theatre. The Frayser-born character actor, famous for playing Deke Slayton in Apollo 13 and for getting into a comic brawl with Joe Pesci in My Cousin Vinnie, has mixed emotions about the engagement. He could be in Denver that night for a screening of Gospel Hill, a film he worked on with Danny Glover and Angela Bassett that’s scheduled to roll opposite the Ossies. (Ellis says there’s a small chance that Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama might attend the screening before the Democratic convention gets under way.) He says he’d love to be there for that. But Memphis is home. Or it was home.

Ellis’ mother recently passed away, and there are loose ends that need tending to on the north side of town. That’s changed the tone of his visit a bit, though he’s been looking forward to the Ostranders and the opportunity to reconnect with a theater scene he holds in high regard.

“I just play my usual ‘Cracker von Peckerwood’ character,” Ellis says, dismissing his performance in Gospel Hill as more of the same. As a spirited fixture on Memphis stages throughout the 1970s and ’80s and as a regular in front of, behind, and occasionally under the bar at Midtown’s P&H Café, Ellis thinks it’s a hoot that he usually portrays Republicans, rednecks, and gruff authoritarian figures.

“When I think of my time as an actor in Memphis, there’s a lot of tenderness,” he says, sitting on a park bench somewhere in rural Maine for a telephone interview. “Tenderness is the best way I can describe it.”

Memphis Flyer: So what’s on your mind?

Chris Ellis: I need to get the roomers out of my mother’s house as soon as possible. The window units are running, I’m told, and all the windows are open. When my mother first came to Memphis from North Mississippi, she took in roomers to make ends meet, and she completed that circle toward the end of her life. And let me tell you about some of the roomers she’s taken on. These are the kinds of people who operate rides at carnivals, get paid in amphetamines, and don’t have many teeth by the time they’re 30.

When did you start doing theater in Memphis?

The first time I was asked to leave Circuit Playhouse was in 1970. I’ve been asked to leave a lot of places since then, including Graceland, Hearst Castle, and the Museum of Tolerance, but I was first asked to leave Circuit in 1970. The story behind that is involved, uninteresting, and complicated.

You worked at other regional theaters as well, not just at Circuit.

I did. But Circuit Playhouse was my entrance to the community of theater in Memphis. It was new. It was closer to where I lived than Theatre Memphis, and it wasn’t as intimidating. Although I’m sure all of this was just in my mind, Theatre Memphis didn’t seem as available back then. There was an “us versus them” attitude. It was [Playhouse on the Square founder] Jackie Nichols versus this much more established company. My heart has always been with Jackie and Playhouse on the Square, because he’s this tap dancer from Ted Mack’s Amateur Hour who started a significant theater company that has consistently done good work. It’s one of those miraculous finishes — one of those last-minute victories that the human race seems to adore.

In various bios I’ve seen, you always cite Memphis as the place where you learned your business.

What I was able to do here as a very young person just out of college was incredible. That was my training and my education. A friend once said if you want to learn to be an actor there are two things you can do: You can study at Juilliard or you can work in the theater with seasoned professionals and watch them as they do their work on stage. And that’s what I did. I watched Memphis actors like Walter Smith, Jay Ehrlicher, Alan Mullican, and Joanne Malin.

When I first went to New York I had something everybody else my age lacked: I’d played significant roles in a couple dozen plays. I don’t know. Maybe nobody cared that I played Rosencrantz in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead or Milo in Sleuth, but that really was my education.

Do you take much of that education into your film roles?

Not really. It’s a very different thing. I didn’t work for 10 years when I lived in New York. I was living in bone-crushing poverty. My hairline was going, and my waistline was growing. My agent said if I’d quit playing [Shakespeare’s] Mercutio and start sounding like a good old boy, I could get work on TV and in film. And so that’s what I did. And I feel so lucky.

You’re also one of those miraculous last-minute finishes. Your career started rolling at 40. That’s about the time most people might think about giving up and moving on to something else. What kept you going?

All I ever wanted to do was to be able to write “actor” on my tax returns — which I didn’t even file for close to a decade when I was so poor. It’s all I ever wanted to do since I was a kid and dreamed that someday I might be able to stand in the same room as Annette Funicello.

I remember doing a show at Circuit with Alan Mullican, a wonderful actor who didn’t make his living in the theater. He made his living as some kind of civil servant working for the state, which wasn’t very fulfilling, and he did theater at night. One time he was very exhausted and I asked, “If you’re so tired, why do you do so much theater?” He looked at me like he didn’t understand and said, “This is what I do.”

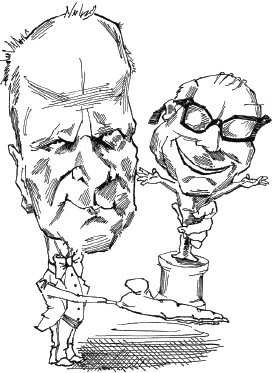

Self-portrait by Chris Ellis, holding an Ostrander award.

You did everything here from performing Shakespeare with Ellis Rabb to playing Lee in Sam Shepard’s True West. Does any role stand out as a high point for you?

Playing Christopher Marlowe in The Passionate Shepherd. Jo Malin directed, and I remember her telling me I was emotionally predisposed to the character but that my voice was my own worst enemy.

I’ll never forget Edwin Howard, the Press-Scimitar‘s theater critic, writing about that show and “Chris Ellis’ new, deeply modulated voice.”

At what point did you realize you were going to have a career in Hollywood?

Probably after the second film, My Cousin Vinnie. That film surprised everybody, because nobody expected it to be a big movie. Before that, I’d worked for 16 weeks on Days of Thunder with Tom Cruise, but I was invisible in that film.

I didn’t really feel like I was in the club until Apollo 13. That’s when I stopped feeling intimidated — when I was made to feel included by the director. Lots of stars are bullies, and lots of producers and directors treat actors like expired goods. That’s not true of Ron Howard and Tom Hanks.

I don’t have any expectations or sense of entitlement. When you’re an actor, you never get the memo that says your career is over. Mine could have been over yesterday. It’s a hard business, especially when your hair starts turning gray. And it’s especially cruel to women. Go to the Internet Movie Data Base and go back 20 years. Find movies by A-list stars like Stallone, Tom Cruise, or Bruce Willis. Look for the names of the leading ladies in these films. Most of the time these will be names you won’t recognize.

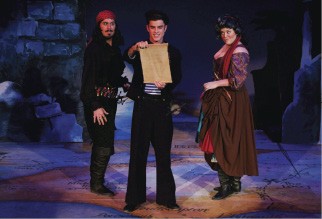

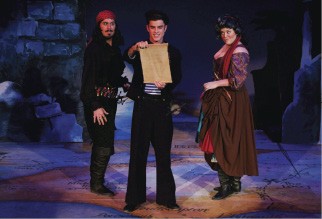

Among the Memphis stage productions nominated for this year’s Ostrander Awards: The Pirates of Penzance (Playhouse on the Square)

What’s next on the horizon for Cracker von Peckerwood?

He’s just finished the second of what he hopes will be a reoccurring role on the TV series Burn Notice. And I worked on a film called G-Force that’s scheduled to be released in 2009. Given the kind of roles I usually play, you might think that G-Force has something to do with aeronautics, but it doesn’t. It’s about gerbils.

Gerbils, really? As in …

No! No. Oh no. It’s animated. I don’t think Richard Gere had anything to do with this movie.

I have to ask, because I remember playing a drinking game at the P&H back in the ’80s called “I Never.” Somebody says, “I never [fill in the blank],” and anybody who’s done that particular thing has to drink …

Ha! Well, there’s nothing I never did.

Yes, the most popular part of that game was when someone would say, “I never [fill in the blank] with Chris Ellis.” Half the table always had to drink.

I once printed up a bunch of T-shirts that said, “I Never Slept With Chris Ellis.” [Actress] Deborah Harrison printed one that said, “I Did. It Wasn’t That Great.”

And the Winner Is …

Twenty-five years ago,

Memphis presented its first theater awards.

by Michael Finger

The men and women who jammed into the Old Daisy that June evening in 1984 were restless. Many glasses of wine tend to have that effect on people, and the various members of the Memphis theater community were rarely known for being anything less than boisterous at parties.

But they quieted down a bit when Barbara Cason stepped to the podium. Cason was the former Front Street Theatre actress who had found success in Hollywood playing bit parts in hit shows like The Waltons and Remington Steele, and she had come home to host a brand-new event in town. In the time-honored tradition of the Oscars, she opened an envelope to announce, “For best dramatic production, the winner is … Amadeus, at Theatre Memphis.”

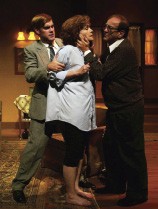

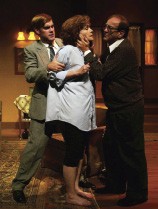

The Night of the Iguana (Theatre Memphis)

And so it went at the first Memphis Theatre Awards, an event sponsored by Memphis magazine that has honored the best and brightest in the local theater community for 25 years.

Memories are a bit foggy — did we mention all that wine? — but Kenneth Neill, now publisher and CEO of Contemporary Media, the company that produces the Flyer, Memphis magazine, and Memphis Parent, recalls that the local theater community wasn’t entirely happy with the coverage they were receiving from our city’s two daily newspapers.

“Back in the 1980s, Robert Jennings was The Commercial Appeal theater critic, and over at the Press-Scimitar it was Edwin Howard, and they just didn’t get along,” Neill says. “It was Sally Thomason, president of the Memphis Arts Council, who mentioned to me one day that it would be nice if they would just cooperate and do something together.”

One thing led to another, and Bob Towery and Neill, publisher and editor of Memphis magazine, respectively, met with Thomason and came up with the idea of an annual competition.

“I think it was a good decision to get the Arts Council involved,” Thomason says. “Ken wanted to give it a community base — something that would lend it a kind of legitimacy that would take it beyond just a magazine project. And I will say this: If it weren’t for Memphis magazine, it would not have happened, and it wouldn’t be here today.” The first year wasn’t easy.

“When we started talking about this, I’m not sure we really had any idea how to proceed,” Thomason says. “We eventually came up with this idea to have a panel of judges, and it was delightful that everyone who got involved was very conscientious.”

The judges for the first Theatre Awards included Walter Armstrong, Gene Crain, Amy Dietrich, Levi Frazier, Stephen Haley, Emily Ruch, C. Lamar Wallis, and Miriam DeCosta Willis.

“We looked for people who were involved in the theater, so they would have some kind of deep knowledge of what they were watching,” Thomason says. “And getting attorney Walter Armstrong was our key, because he seemed to go to everything. I remember he said, ‘I’m tired of raising money for the arts, but this is something I can really put my heart into.'”

Ruch had been involved with the local theater community since 1954, performing on stage and serving on the play selection committee for the old Memphis Little Theatre. She took her judging responsibilities quite seriously.

“I wouldn’t even have a glass of wine before I went to a play,” she says, “and I would take notes in my program and go home and write up what I thought, right away, while it was still fresh.”

Ruch adds that the various judges weren’t even supposed to talk to each other during the year.

“We could not go to a play together, because we didn’t want to be influenced by the other person,” she says. The judges met at Armstrong’s house at the end of the season to select the winners.

“We met all day and all night,” says Ruch, “and we really followed the rules. We were very honest about it. We wanted to acknowledge all theaters, but we didn’t give an award to a theater just because they hadn’t gotten one.”

The winners that first year included:

• Best dramatic production:

Amadeus, Theatre Memphis

• Best performance by an actor:

Jay Ehrlicher, Amadeus

• Best performance by an actress:

Pamela Poletti, The Miracle Worker,

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Circuit Playhouse)

Playhouse on the Square

• Best musical production:

Handy, Theatre Memphis’ Little Theatre

• Best set design:

The Dresser, Circuit Playhouse.

A special award for “service to Memphis theater that spans generations” went to Eugart Yerian, director of the Memphis Little Theatre from 1929 to 1961. (The following year, the award itself was named the Eugart Yerian Award.)

“We won quite a few awards that evening,” says Jackie Nichols, executive producer of Playhouse on the Square and Circuit Playhouse. “It was kind of small that year, and after the first glass of wine, or two, you don’t remember much about it. But it was Memphis magazine’s way of honoring the theatrical tradition that has always been so awesome in Memphis. And I don’t want to speak for him, but I guess it was Ken’s way of wanting to give something back to the community, and the art form he chose to honor was theater.”

The theater awards grew and prospered, especially when Janie McCrary, who was then working at the Arts Council, took over the judging.

“Memphis magazine would produce the event, and the Arts Council would get the judges together,” McCrary says. “At first it was, let’s just see what we can do here. But then we came up with more rules, more criteria, and after the first few years it became a bit more structured.” The awards themselves are now called the Ostranders, named in honor of Jim Ostrander, one of the city’s most popular actors, who died of cancer in 2002.

Ruch, who served as a judge for the first three years, remembers her colleagues felt a keen responsibility to do it right back in 1984.

“We were very aware that we were the first,” she says. “And we were very aware that we were doing something that would be deliberately continued or deliberately not continued, so I don’t think I’ve ever seen such dedicated people.” That dedication has clearly paid off.

Looking back to that first competition, Ruch remembers, “We took ourselves very seriously, but it was fun, fun, fun.”

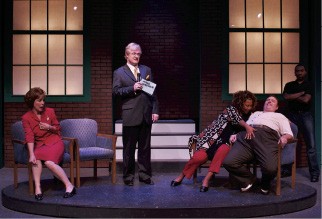

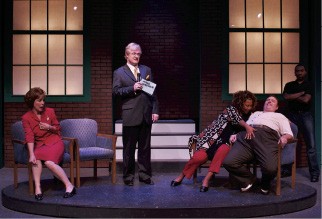

Jerry Springer: The Opera (Playhouse on the Square)

25th Annual Ostrander Awards

Sunday, August 24th

Memphis Botanic Garden

Cocktails: 6 p.m.; awards: 7:30 p.m.

Tickets: $5, $6 at the door

. . . . . . . . . .

Talks to Angels …

Arts patron Dorothy Kirsch

is honored for lifetime achievement.

by Chris Davis

By all accounts, Dorothy Orgill Kirsch, the winner of this year’s Eugart Yerian award for lifetime achievement in Memphis theater, is the single most caring, genuine, funny, energetic, and loving person who ever patronized the arts or loved animals way too much.

Kirsch isn’t an actress, though she’s been on stage once or twice. Kirsch is a volunteer and a philanthropist, the kind of person theater folks rightly call an angel. She’s supported an array of artists, filmmakers, and institutions, ranging from Ballet Memphis and the Hattiloo Theare to Voices of the South.

Whitney Jo, Playhouse on the Square’s managing director, says Kirsch has a critical edge as well. “There have been a couple of occasions where she’s seen a show and was very vocal about everything that was wrong with it.” Jo says the criticism goes down easier when it comes from somebody who sponsors productions and gives to capital campaigns.

“Dorothy has believed in the work of Voices of the South from the get-go,” says Jenny Odle Madden, the group’s executive director. “She loves our adaptations of Southern stories. There is not another arts patron like her.”

Memphis Flyer: Most people think of you as an arts enthusiast, but you’ve been on stage a time or two, haven’t you? I remember seeing your name in the program for A Streetcar Named Desire at Theatre Memphis. Were you Stella? Blanche?

Kirsch: HA! I was a bag lady.

Describe yourself in a million words or less.

Lucky enough to do the things I love.

When did you decide that theater was your thing?

Well, I was very fortunate, and as a pre-teenager back in the Dark Ages, I would go to the theater whenever the family went to New York. I also remember going to shows in Memphis at the Front Street Theatre when it was in the basement of the King Cotton Hotel.

What pleases you the most?

I love dance. I love good comedy. The great thing about theater is that you can go back to see the same show, and it’s different every time. I think I saw Nunsense five times.

Do you have an all-time favorite show?

Uncle Vanya with Ken Zimmerman and Jim Ostrander. And Theatre Memphis’ Cats.

For a list of Ostrander Award nominees (and next week’s winners, once they’re announced), go to memphisflyer.com and search “Ostrander.”