With “jazz month” drawing considerable attention and attendance at Crosstown Arts for the past two weeks, encompassing everything from hard bop to the city’s burgeoning avant garde scene, it’s worth taking a step back to consider an artist who mastered all those styles and more: Sun Ra.

The fact that both he and his longtime saxophonist John Gilmore were from the South (Birmingham, Alabama and Summit, Mississippi, respectively) makes them all the more relevant to the current moment, above and beyond the fact that Ra’s legacy informs all artists who walk the line between “inside” and “outside.” Those words, of course, are jazz lingo for playing inside the lines of conventional chord changes versus stepping outside into a world of free improvisation.

That line matters when it comes to Sun Ra — born Herman Poole “Sonny” Blount — as the mere mention of his name these days is often used to signify any music that’s outlandishly free or experimental. What’s often forgotten is that, behind the sci-fi-influenced language and costumes of Ra’s futurism, there was a disciplined composer and arranger who revered Fletcher Henderson scores dating back to the 1920s. That’s not to say that the Sun Ra Arkestra didn’t have its moments of more chaotic improvisation, but they were only partial refractions of the ensemble’s wider palette of sounds.

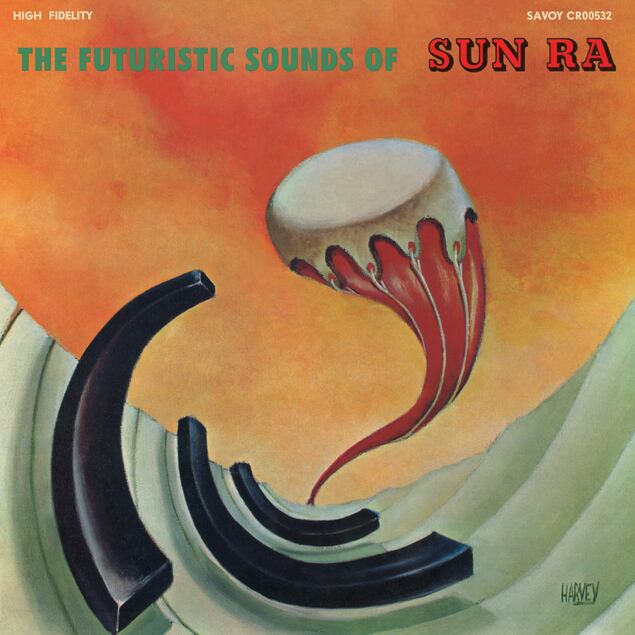

The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra, first released on Savoy Records in 1962, then re-released last fall on 180-gram vinyl, CD, and hi-res digital by Craft Recordings in honor of its 60th Anniversary, is a good case in point. It was an historical milestone, being the first recording made with his band, The Arkestra, after moving to New York from Chicago. Produced by Tom Wilson (who would go on to produce Bob Dylan, the Velvet Underground, and the Mothers of Invention, among others), The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra has long been considered one of the avant-garde artist’s most accessible albums.

According to John Szwed’s Space is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, the album was not even reviewed at the time and immediately sank into obscurity. So much for being accessible! And yet, compared to what came later from the Arkestra, this album is indeed approachable, and a good entry point into Sun Ra’s oeuvre for listeners hoping to expand their horizons.

It’s “a record which could have easily represented their repertoire during an evening at a club” at that time, as Szwed writes, with a listenable balance between free improvisation and composed pieces for an octet. The latter pieces are not so different from other cutting edge, large-ensemble jazz albums of the time, such as Gil Evans’ Out of the Cool (1960), Charles Mingus’ Oh Yeah (1961), or Oliver Nelson’s The Blues and the Abstract Truth (1961).

That’s apparent right from the start, as “Bassism,” beginning with a sparse bass line, soon incorporates tight horn bursts and grooving piano before making room for a more freestyle flute from Arkestra stalwart Marshall Allen. The tracks continue in that vein, mixing tightly arranged horn lines, piano vamps, and freer soloing in relatively concise compositions. With “Where Is Tomorrow,” the arranged horns soon drop out to make way for intriguing freestyle interplay between two flutes and bass clarinet (the latter played by Gilmore).

That “outness” takes over on the next track, “The Beginning,” which begins and ends with a melange of unorthodox percussion. The album liner notes tout this element, noting that the record features bells from India, Chinese wind chimes, wood blocks, maracas, claves, scratchers, gongs, cowbells, Turkish cymbals, and castanets. These flourishes lend a distinctive sonic stamp to the entire album.

At times, the mood mellows, as with “Tapestry from an Asteroid,” a ballad that became one of Ra’s most-performed works. Interestingly, out of the 10 original selections on the album, “Tapestry from an Asteroid” would stand as the only work that the artist would ever revisit — on stage or otherwise — again. “China Gates” is also in this mood (and is the sole track not written by Ra), with vocalist Ricky Murray sounding almost like Billy Eckstine amid the bells and gongs.

Following the release of Futuristic Sounds, which marked Ra’s sole album under Savoy, the artist and the Arkestra enjoyed a fruitful period in New York and Philadelphia. In 1969, Ra graced the cover of Rolling Stone. In the early ’70s, he became an artist-in-residence at the University of California, Berkeley. Later in the decade, back in New York, his shows would attract a new generation of fans, including the Velvet Underground’s John Cale and Nico. As he grew older, Ra’s influence only continued to grow, with bands like Sonic Youth inviting the artist to open for them. During his lifetime, Ra also built one of the most extensive discographies in history, which includes more than 100 albums (live and studio) and over 1,000 songs. And now, nearly 30 years after his death, the legacy of Sun Ra lives on through the ever-evolving Arkestra, which continues to record and perform today under the leadership of the forever-young Marshall Allen.